When is Debt Unsustainable?

Two economists who are inspirations to me are Steve Keen, who publishes Debtwatch, and Mike Shedlock, who publishes Global Economic Analysis. I found them while trying to make sense of the credit bubble, and finding little or nothing forthcoming from the mainstream economic community. But Keen and Shedlock provided insights when most experts were silent, and they still do. I remember the summer of 2005, driving up Highway 99 in California’s Central Valley, and seeing a billboard advertising “ranchettes” that were “starting in the low $600,000’s” – in the middle of nowhere – in a state with a median household income of $60,000! People were buying homes that cost ten times their annual earnings.

A scathing recent post from Keen, “How I Learnt to Stop Worrying and Love the Bank,” and Shedlock’s “World Economic Forum Embraces Fraud,” followed by Keen’s response to Shedlock on the same topic, “Mish Mashes the WEF,” all reinforce this sad suspicion: Mainstream economists who think we can avoid deleveraging are still strangely clueless, or worse, they are in collusion and have a hidden agenda.

In Shedlock’s post, he calls attention to the report recently released by the WEF entitled “More Credit with Fewer Crises – Responsibly Meeting the Worlds Greater Demand for Credit.” Here is an excerpt from the press release for the WEF study, “Credit levels will need to double over the next 10 years, growing by US$ 103 trillion, to support consensus-projected economic growth. This doubling of credit could be achieved without increasing the risk of major crisis…” and here is Shedlock’s response, “The accompanying PDF [the WEF report] entitled “More Credit with Fewer Crises” is 84 pages of economic claptrap. The main mission of the World Economic Forum appears to cram more credit down the throats of a world so stuffed with credit it cannot possibly be paid back.”

In Keen’s 2nd post on the WEF report, he highlights one of Shedlock’s many criticisms of the WEF’s assumptions, just one example of the astonishing vacuousness of this report. Here is an excerpt from the report where the WEF economists suggest that total debt can increase at a faster rate than GDP indefinitely:

“This means that the world’s stock of credit outpaced GDP growth by less than 2 percentage points a year – not a wide margin. In theory, there is nothing unsustainable about this picture: as long as credit grows broadly in line with economic growth, the credit is put to good use and borrowers can meet interest obligations and repay principal.”

And here is Keen’s response to this preposterous claim by the WEF:

“The American mathematician Andrew Bartlett claims that ‘The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function,’ to which I’d add that that shortcoming almost defines neoclassical economics. 2 percent per annum doesn’t sound like a lot, but over 36 years that means the ratio doubles, over 72 it quadruples, over 144 it becomes 8 times what it was, and so on. For the record, the actual rate of growth of the private US debt to GDP ratio was roughly 2.9% p.a. from 1945 till 2008. That means that the ratio doubled every 25 years, from 45% in 1945 to 90% in 1970, 180% in 1995, and if it had kept going, it would have been 360% in 2020.”

So when is debt unsustainable? In my recent post “National Debt and Rates of Return,” using crude estimates and assumptions, I attempted to calculate the total debt to asset ratio for the U.S. and other major nations. The total debt numbers for the U.S. are well documented; the other total debt numbers are informed guesses. Then, in an attempt to determine when debt becomes unsustainable, in column four I calculated “available credit” based on available credit being 50% of total assets, with (another crude assumption) total assets calculated as 10x GDP. Here is that chart again:

A reason to like this chart is because one may insert any set of assumptions they wish to estimate total assets as a multiple of GDP and total available credit as a percentage of total assets. Those numbers, while unknowable, are real. If debt expands faster than GDP for a prolonged period of time, even if the gap is only 2% per year, sooner or later collateral cannot support debt.

A reason to like this chart is because one may insert any set of assumptions they wish to estimate total assets as a multiple of GDP and total available credit as a percentage of total assets. Those numbers, while unknowable, are real. If debt expands faster than GDP for a prolonged period of time, even if the gap is only 2% per year, sooner or later collateral cannot support debt.

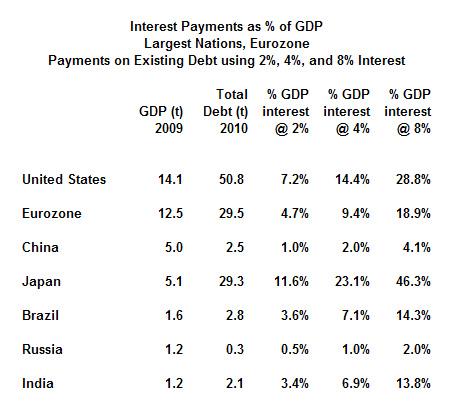

The next chart from that post also speaks to a concern I share with Keen and Shedlock, and perhaps even the WEF economists who dare not speak the word: Deflation. Because if total debt as a percentage of total assets grows because the rate of debt expansion continues to outstrip the rate of GDP growth, interest rates eventually have to rise to cover the increased risk. The less secure the collateral is, the higher the risk premium has to be.

This chart explains the paradox facing global bankers, and threatening the financial security of everyone in the global economy. If interest rates rise they will place an unbearable claim on global GDP, causing defaults. If interest rates stay low, debt/asset ratios will edge closer and closer to 1.0, worsening the eventual and inevitable process of deleveraging.

This chart explains the paradox facing global bankers, and threatening the financial security of everyone in the global economy. If interest rates rise they will place an unbearable claim on global GDP, causing defaults. If interest rates stay low, debt/asset ratios will edge closer and closer to 1.0, worsening the eventual and inevitable process of deleveraging.

The question is does the ability of inflation to lower the real principal value of debt – which improves the debt/asset ratio – more than make up for the burden higher interest rates place on cash flows? The WEF is making this bet, perhaps because it is the only bet they have left.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Mish Shedlock is most certainly NOT an economist. He’s a security salesman.

Skipping Dog: When formally trained economists told us we didn’t need to have any concerns about the economy back in the summer of 2005, when the average new home price in California was ten times the average household income, and everyone in sight was borrowing and spending every penny they could against their home equity, yet the rate of economic growth was barely positive enough to avoid declaring a “recession” had begun, it’s time to start relying on your own judgment and observations. It would take a bit more effort, but maybe if you would explain exactly where the flaws are in Mike Shedlock’s arguments, instead of simply attacking his credentials, your comment would be more helpful.

Beware of the experts. After all, they are the ones that got us in this mess and advised to use home equity for investment. I was lucky. I had an annuity for 20 years. The principal was 126K and I cashed out a few months before the crash due to the handwriting on the wall for $196K. Doing some backward math, I could have had a similar return in CDs with no risk. My fund was professionally handled. Sure, the bought stuff that they were bribed to buy and I took the risk. I was lucky to bail when I did. Now, it is all in CDs making .89%, but I did not lose principle. Lucky? I was scared by what I read and I bailed against the advice of my agent that said, “You stepped in, step out so you get those big gains in the stock market.” HA!

Do you know of any reliable source in somewhat easy to understand terms that tells what the total state budget is (not just general fund), the total local funds are, and what the combined state and local payrolls plus retirements are? I can not find this anywhere that I think I can figure out or trust.

I am sick and tired of hearing rubbish about the “US economic recovery”. The US government borrowed and spent $6.1T over the past four years to generate a cumulative $700 billion increase in the nation’s GDP. That means we’ve borrowed and spent $8.70 for every $1 of nominal “economic growth” in Gross domestic product. In constant $, GDP is flat, we got no “economic growth” at all for our $6.1 trillion. In constant US dollars, the GDP in 2011 might return to the 2007 level, if the economy continues “growing” at the same pace reached in the first three months of 2011. If not, then the GDP will in reality be lower than pre-recession levels. There is no recovery, the numbers prove it.