California’s Government Worker Pensions Are Bankrupt

As reported today in Capitol Weekly, in a post entitled “CalPERS ignores Brown, delays pension payment” by Ed Mendel, the amount taxpayers will have to fork over to CalPERS next year will rise by $213 million, to a total of $3.7 billion. Governor Brown, quite rightly, believes the full amount of the necessary increase should have been assessed, another $149 million, instead of being “smoothed” over the next twenty years.

But CalPERS – the largest of over 30 major government worker pension funds in California, only manages about a third of the the state and local public sector pensions. And CalPERS is basing their increase on a lowering of their projected rate of return for their invested funds by one quarter of one percent, from 7.75% down to 7.5%.

People may debate endlessly over whether or not government worker pension funds in America, now managing over $4.0 trillion in assets, can actually earn 7.5% per year, every year, for decades on end. We have argued repeatedly that this rate of return is impossible to achieve any longer, because (1) high returns in the past depended on debt accumulation, which poured cash into the economy, which stimulated consumer spending, investing, and asset appreciation – enabling more borrowing – all of which caused investment returns to grow at levels that cannot continue now that borrowing has reached its practical limit, (2) our aging population means more people will be selling their investments to finance their retirements – including the pension funds whose participants themselves are aging and are retiring with higher benefits than previous retirees – and this puts more sellers in the market, lowering asset values and returns on invested assets, and (3) pension funds are much larger as a percent of GDP than they were in previous decades, and they are now too big to consistently beat the market.

This debate will not go away. But it is at least worth examining just how much it will cost Californians if the rates of return on state and local government worker pension funds drops by 1.0%, 2.0%, or 3.0%. The fact is, they might drop by even more than that. Go to a commercial bank and try to buy a U.S. Treasury bill or certificate of deposit that pays 4.75%. Or examine the returns on the major stock exchanges over the past 10+ years. Yields are well under 4.75%, yet CalPERS has lowered their rate of return by only one-quarter of one percent to 7.5?

What are they scared of? Why not pick a risk-free, much lower rate of return?

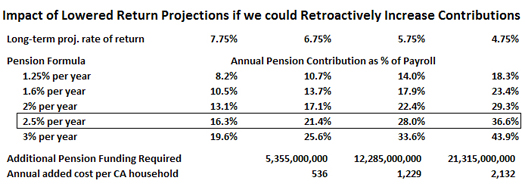

The table below shows how much the annual pension contribution as a percent of payroll increases when the rate of return drops. Column one shows the contributions required under the original 7.75% long-term rate of return projection, which has just been lowered to 7.5%. Columns two, three and four show the contributions required under lower rates of return, 6.75%, 5.75%, and 4.75%. The rows show just how much these contributions need to be under various pension formulas. These formulas govern most government worker pensions – the percentage noted, “1.25% per year,” for example, means that if a government worker retires after 30 years, their pension will be calculated as follows: 1.25% x 30 x final salary, or in this case, 37.5% of final salary. The amounts selected for these rows are representative of the following pension formulas:

- 1.25% per year – for typical non-safety employees up until around 2000.

- 1.6% per year – the average of non-safety and safety employees up until around 2000.

- 2.0% per year – for typical safety employees up until around 2000; for typical non-safety employees since then.

- 2.5% per year – the average of non-safety and safety employees since around 2000.

- 3.0% per year – for typical safety employees since around 2000.

On the table below, row four of the pension formulas, outlined, shows how lowered rates of return will impact the contributions necessary to fund a 2.5% per year formula. Since 2.5% per year is the blended average that would represent all current state and local government employees in California, the results in this row should be of great interest to taxpayers and public employees alike. As can be seen in this case, the annual pension contribution as a percent of payroll must increase from 16.3% at the rosy rate of return of 7.75% to 21.4% (at 6.75% return), to 28% (at 5.75% return), to 36.6% (at a still impressive 4.75% rate of return).

The table above concludes by taking these pension contributions and applying them to the total payroll of California’s state and local governments, which is (using conservative estimates) 1,500,000 employees times an average annual salary of $70,000 per year (ref. U.S. Census, 2010 CA State Gov. Payroll, and 2010 CA Local Gov. Payroll). As can be seen, if the rate of return for California’s state and local government employee pension funds drops from 7.75% to 6.75%, this will cost taxpayers another $5.4 billion per year. If the return projection drops to 5.75%, it will cost taxpayers another $12.3 billion per year. And if the return projection drops to 4.75% per year, it will cost taxpayers an additional $21.3 billion per year. But wait, because the above analysis still understates the problem.

The table above concludes by taking these pension contributions and applying them to the total payroll of California’s state and local governments, which is (using conservative estimates) 1,500,000 employees times an average annual salary of $70,000 per year (ref. U.S. Census, 2010 CA State Gov. Payroll, and 2010 CA Local Gov. Payroll). As can be seen, if the rate of return for California’s state and local government employee pension funds drops from 7.75% to 6.75%, this will cost taxpayers another $5.4 billion per year. If the return projection drops to 5.75%, it will cost taxpayers another $12.3 billion per year. And if the return projection drops to 4.75% per year, it will cost taxpayers an additional $21.3 billion per year. But wait, because the above analysis still understates the problem.

There’s one more big gotcha.

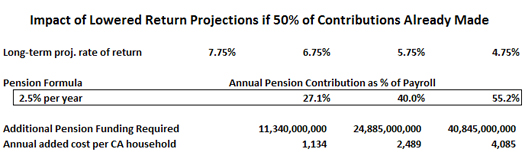

The first table is entitled “Impact of Lowered Return Projections if we could Retroactively Increase Contributions.” But we can’t do that. Contributions that are in the funds currently were made under the assumption that the 7.75% rate of return would last forever. If we lower that assumption, we still have to fund our pension obligations by investing the money we’ve already got, plus whatever additional monies we can collect from now on. This severely compounds the problem.

The next table, below, calculates how much lowered return projections will cause pension contributions to increase, if half of the contributions are already made. This assumes that in aggregate, the participants in California’s government worker pensions are at mid-career. This is an extremely conservative assumption, because there are millions of government workers who are already retired, whose pension payments are equally dependent on investment returns from the pension funds. This next table therefore understates the impact of lower investment returns on the required contributions to the fund from existing workers.

As can be seen in this more realistic, but still very much a best case scenario, if the rate of return for California’s state and local government employee pension funds drops from 7.75% to 6.75%, this will cost taxpayers another $11.3 billion per year. If the return projection drops to 5.75%, it will cost taxpayers another $24.9 billion per year. And if the return projection drops to a still quite aggressive 4.75% per year, it will cost taxpayers an additional $40.8 billion per year.

This is what the pension funds are up against. These are the scenarios the pension bankers exchange in closed meetings, where the press and even their own PR people don’t attend. Imagine if CalPERS admitted, as they should, that their funds cannot reliably expect to earn more than 4.75% per year. It would mean that – assuming all 10 million of California’s households pay taxes, which obviously is not the case – that every household in the state would have to fork over another $4,000 per year in increased taxes.

This is what the pension funds are up against. These are the scenarios the pension bankers exchange in closed meetings, where the press and even their own PR people don’t attend. Imagine if CalPERS admitted, as they should, that their funds cannot reliably expect to earn more than 4.75% per year. It would mean that – assuming all 10 million of California’s households pay taxes, which obviously is not the case – that every household in the state would have to fork over another $4,000 per year in increased taxes.

Critics of pensions and critics of pension reform alike are invited to verify for themselves the calculations made here. To imply, as CalPERS has, that about another $1.0 billion per year, spread among the 30 California government worker pension funds and “smoothed” over the next 20 years, is all it will take to shore up their solvency, is irresponsible. The additional amount necessary to save California’s government worker pensions is probably closer to $40 billion per year, from now until these pension formulas are reduced.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!