California’s Green ‘Bantustans’ Are Coming to America

If the “smart growth” urban planners that dictate land use policies in Democratic states and cities have their way, the single family dwelling is an endangered species.

In Oregon, proposed legislation would “require cities larger than 10,000 people to allow up to four homes to be built on land currently zoned exclusively for single-family housing.” In Minneapolis, recent actions by the city council mean that “duplexes and triplexes would be allowed in neighborhoods that only previously allowed single-family housing.”

The war on the detached, single family home, and—more to the point—the war on residential neighborhoods comprised exclusively of single family homes, is on. And it’s gone national.

In California, ground zero for this movement, state legislation now requires cities and counties to fast track permitting for “accessory dwelling units.” This scheme will allow developers and ambitious homeowners to construct detached rental homes in their backyards, but since they’re called “accessory dwelling units,” instead of “homes,” they would not run afoul of local zoning ordinances that, at one time, were designed to protect neighborhoods from exactly this sort of thing.

“Smart growth,” however, began long before the home itself came under attack.

First there was the war on the back yard. Large lots became crimes against the planet—and if you doubt the success of this war, just get a window seat the next time you fly into any major American city. In the suburbs you will see a beautiful expanse of green, spacious, shady neighborhoods with lots designed to accommodate children playing, maybe a pool or vegetable garden, big enough for the dog.

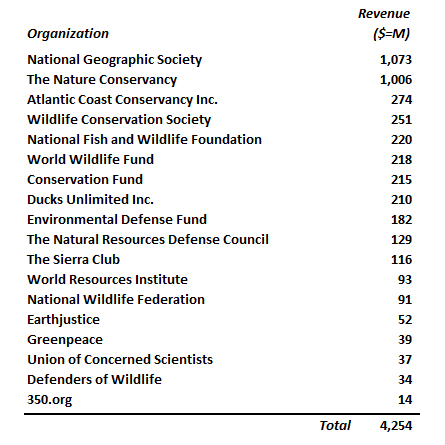

But you will also see, plain and obvious, those suburbs that were built after the smart growth crowd came along. Tight, treeless, and grey, with homes packed against each other, these are the Green Bantustans, and there’s nothing green about them.

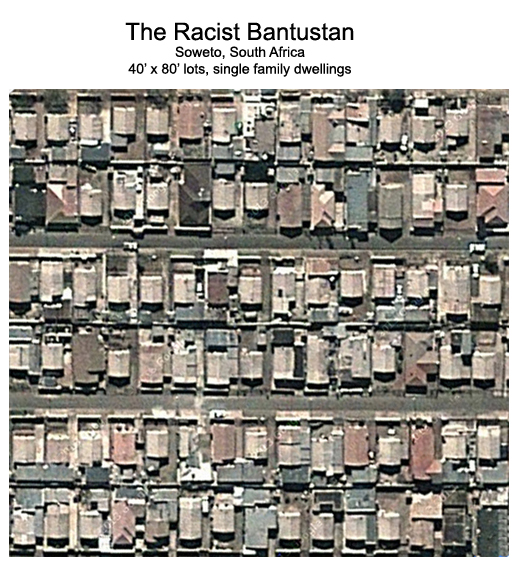

The image below shows homes packed roughly 15 per acre—including the streets—on private lots that are 40-feet wide by 80-feet deep. As of January, these homes were selling for $350,000. Such a deal! Smart growth!

Why call neighborhoods with mandated ultra-high density “Green Bantustans”? Because the Bantustan was where a racist elite used to herd the African masses during South Africa’s apartheid era. The commonality between the Green Bantustan and the Racist Bantustan becomes clear when you step back and ponder what is happening. In both cases, a privileged elite condemn the vast majority of individuals to live in a concentrated area designed to minimize their impact on the land.

But in America, the “smart growth” advocates aren’t racists, they’re misanthropic environmentalists.

The image below is fascinating, because at the same scale, it shows a neighborhood in the township of Soweto, once touted as a poster child for one of the most chilling warehouses for human beings in history. But notice the size of the lots—40 feet by 80 feet—are identical in size to that Green Bantustan in California. Also, please note, it’s probably much easier to get a building permit in Soweto.

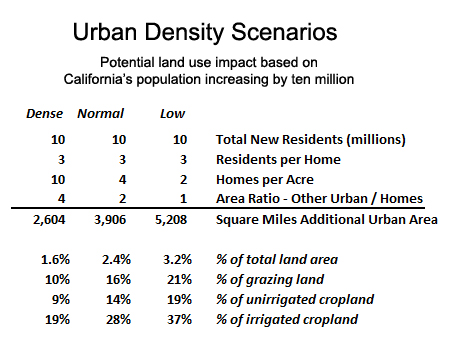

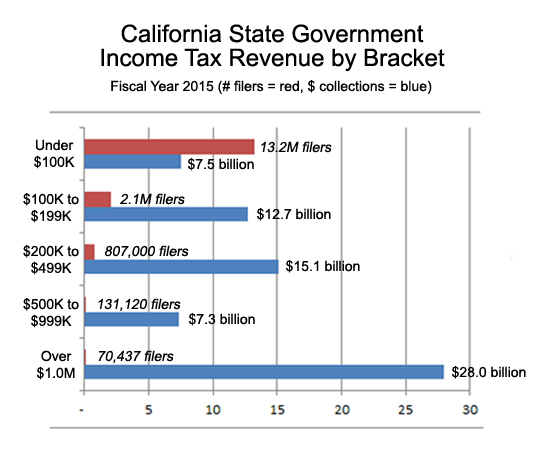

The above chart depicts three urban growth scenarios, all of them assuming California experiences a net population increase of 10 million, and that all new residents on average live three people to a household (the current average in California is 2.96 occupants per household). For each scenario, the additional square miles of urban land are calculated.

As the chart shows, adding 10 million new residents under the “low” density scenario would only use up 3.2 percent of California’s land. If all the growth were concentrated onto grazing land—much which is being taken out of production anyway, it would only consume 21 percent of it. If all the growth were to fall onto non-irrigated cropland, which is not prime agricultural land, it would only use up 19 percent of that. Much growth, of course, could be in the 58 percent of California not used either for farming or ranching.

Two key points about these data bear emphasis. First, there is plenty of room for low-density development for millions of new residents, not only in California, but elsewhere in the United States. As shown in this example, moving 10 million people into homes on half acre lots, with no infill within existing urban areas, would only consume a small fraction California’s land area.

Second, even the dense scenario depicted on the first column the chart, cramming ten homes onto each developed acre, is not acceptable to the smart growth crowd. The policy goal in California, and elsewhere as noted, is to channel as much new development as possible into the confines of existing cities, and overwhelmingly favor multi-family dwellings over single-family detached homes.

“Smart Growth” is Not Smart, It’s Just Cruel

None of this is necessary. The idea that American policymakers should enforce urban containment is a cruel, entirely unfounded, self-serving lie.

The lie remains intact no matter the context. If there is an energy shortage, then develop California’s shale reserves. If fracking shale is unacceptable, then use safe land-based slant drilling rigs to tap natural gas in the Santa Barbara channel. If all fossil fuel is unacceptable, then build nuclear power stations in the geologically stable areas in California’s interior. If there is a water shortage, then build high dams. If high dams are forbidden, then develop aquifer storage to collect runoff. Or desalinate seawater along the Southern California coast. Or recycle sewage. Or let rice farmers sell their allotments to urban customers. There are answers to every question.

Environmentalists generate an avalanche of studies, however, that in effect demonize all development, everywhere. The values of environmentalism are important, but if it weren’t for the trillions to be made by trial lawyers, academic careerists, government bureaucrats and their government-union overlords, crony green capitalist oligarchs, and government pension-fund managers and their partners in the hedge funds whose portfolio asset appreciation depends on artificially elevated prices, environmentalist values would be balanced against human values.

The Californians who are hurt by urban containment are not the wealthy people who find it comforting to believe and lucrative to propagate the enabling big lie. The victims are the underprivileged, the immigrants, the minority communities, retirees who collect Social Security, low wage earners, and the ever-shrinking middle class.

In America, it used to be that refugees from California who aspired to improve their circumstances could move to somewhere like Houston and buy a home with relative ease. Watch out. That is changing. The masses are being herded into Green Bantustans, as America turns into a petri dish for the privileged upper class, backed up by a fanatical Earth First movement.

This article originally appeared on the website American Greatness.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.