Huntington Beach Denies Pandemic Reality, Dispenses Pay Raises

On April 6 the Huntington Beach City Council agreed to pay raises for police officers and city employees. The cost for these raises over the next three years is estimated at $5 million.

In a city that reported general revenues of $188 million in the fiscal year ended June 2019, this raise can accurately be described as small potatoes. Furthermore, in that year the city reported total revenues exceeding total expenses by $25 million. So what’s the big deal?

There are two big problems with this decision by the Huntington Beach City Council. First, and glaringly obvious, is the fact that the revenue incoming to the city has imploded, and there is no end in sight. As Mayor Pro Tem Jill Hardy – a Democrat – said in the council meeting, “how do we ensure we are still a functioning city later if we pay more now.” Hardy went on to remind her peers on the council of past “deals we wished we could take back when the economy got bad.”

This problem, maintaining or even increasing pay and benefits in spite of a bad economy, is a well established pattern in California’s union controlled cities. Just twenty years ago, in the aftermath of the internet bubble popping, city after city went ahead anyway and implemented pension benefit enhancements. Following the precedent set by SB 400 in 1999 – when the internet bubble was still fully inflated – city after city yielded to pressure from CalPERS and their public employee unions to ensure they too would get bigger and better pension benefits.

They did this despite an economy still reeling from the collapse of tech stocks. They did this heedless of an untenable spread between the cost of money – borrowing rates near zero – and the supposed return on investment promised by the pension funds, over 7 percent. That problem, of course, is worse than ever.

Then in 2009, as the U.S. economy slid even closer to the edge of the abyss, with government tax revenues cratering, California’s public employees took “furloughs,” whereby they took one day a week off without pay. The key fact of this supposed sacrifice was that their rate of pay did not drop one iota. They worked less, and got paid proportionally less. They did this while in the private sector whoever wasn’t completely out of a job was accepting a lower rate of pay with gratitude, because at least they still had a job. They were working as hard as ever.

This is the context of what just happened in Huntington Beach, and if it is the harbinger of similar actions in the rest of California’s cities, then we’ve learned nothing from recent experience.

The litany of what California’s cities are in for this time is already well scripted and already overplayed for anyone paying attention, but for Huntington Beach in particular, here’s a snapshot:

In FYE 6/30/2019 the city collected $89.1 million in property taxes, $47.4 million in sales taxes, $18.8 million in utility taxes, and $14.0 million in transient occupancy taxes. How far are those collections about to fall?

By the end of this fiscal year, Huntington Beach will have endured nearly five months of a catastrophic slowdown. With most retail businesses closed, expect sales tax receipts down by around $10 million. With nearly all types of businesses closed, expect utility taxes to also fall, probably by another few million. With the hotels closed up almost entirely, expect transient occupancy taxes to also be down by a few million. Figure the city’s revenues will drop by $15 million in the current fiscal year, maybe more.

But next year could be worse. Huntington Beach is a tourist mecca, with surfing competitions, art shows, air shows, volleyball tournaments, and the longest pier on the west coast. Literally millions of tourists visit Huntington Beach every year. Will they fill the hotels and beaches in the summer of 2020? Will all of these planned events take place? And what about property values? What is going to happen if property values fall, imperiling Huntington Beach’s largest source of revenue?

In their annual report, Huntington Beach touts their financial resiliency in the face of “industry specific downturns.” But they are not protected against general economic downturns, and their tourism industry, along with their stratospheric property valuations, render them more vulnerable in a severe recession, not less.

While Revenues are Going Down, Expenses are Going Up

Maybe the raise awarded Huntington Beach’s city employees was not a big portion of their total annual expenses, less than one percent. But Huntington Beach is liable to be looking to cut expenses wherever they can in the coming years, because their required payments to CalPERS are heading way up. This problem, dramatically escalating annual pension contributions, is not a trivial budget item, it’s hitting every city in California, and it was set to wreak financial havoc even before this pandemic triggered downturn made everything much worse.

Referencing the public agency actuarial reports provided by CalPERS for Huntington Beach’s miscellaneous and safety employees, and as confirmed by the authors of Huntington Beach’s otherwise glowing financial report for FYE 6/30/2019, pension payments are going to eat that city up. Quoting from the annual report:

“CalPERS has instituted aggressive funding schedules in order to reach 100% funded status within the next 20-30 years, resulting in dramatic increases to the City’s UAL payments from $4.58 million in FY 2008/09, $24.93 million in FY 2018/19, up to a staggering $46.02 million in FY 2029/30.”

Not mentioned in the annual report, but available on the actuarial tables are the immediate hikes in CalPERS payments. They will rise by $5.0 million year over year to 29.9 million in 2019-20, and then in an ongoing series of sharp steps upwards will hit $40 million by 2023-24. The strategy being pursued by Huntington Beach, at least according to their annual financial report, is to attack their nearly half-billion dollar unfunded pension liability another way, through pension obligation bonds.

This is an interesting strategy these days, because low interest rates have filtered all the way down to the POB market, and money can be borrowed on 20 year terms for just 3.0 percent. As of 6/30/2019 Huntington Beach’s officially recognized unfunded pension liability was $436 million, which represented a 67 percent funded system. It’s certainly worse by now, so assume they borrow $500 million to get themselves fully, or nearly fully funded. This would result in payments of $33 million per year. That is considerably less than the projected UAL payments.

The only thing irrational about borrowing at low interest rates to fully fund employee pensions might be, sadly, that if this rescues the city’s cash flow, the unions come back and demand even more money.

Which brings us to the second problem with granting a raise to city employees in Huntington Beach; they already do very well for themselves.

How Much Do Huntington Beach Employees Make?

For a visceral answer to this question, look no further than Transparent California’s salary report for Huntington Beach, where 107 employees were reported to have total pay and benefits in excess of $300,000 during 2018, and an incredible 331 employees had total pay and benefits in excess of $200,000. To put this in perspective, during 2018, there were only 766 employees who completed the full year as full-time employees with full benefits.

It’s fair to question the Transparent California data, however, because the analysts include a column called “Pension debt,” where a substantial amount appears. This is where they have allocated, on a pro-rata basis, the unfunded liability payment which agencies stopped doing back in 2017 – ostensibly to make reporting more accurate. The effect of this omission by California’s reporting agencies was to make it look like these employees made less in total compensation. But shouldn’t the cost to pay down the unfunded liability be considered part of an employee’s compensation?

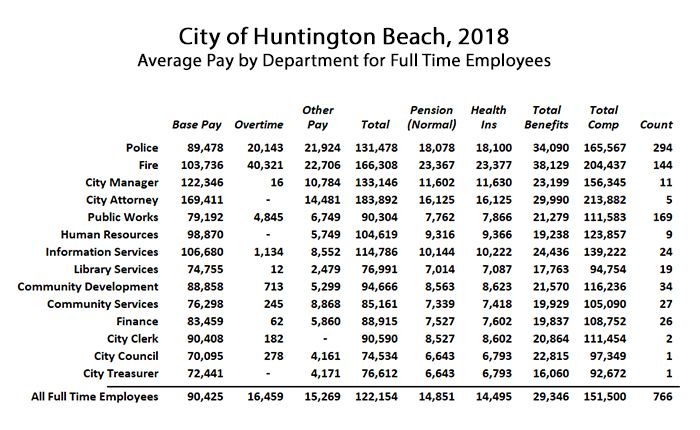

Answering that question completely is a subjective exercise in futility, and only the most hardened nerds would find the discussion even remotely interesting. So instead, here is a table that uses State Controller data, downloaded from the state controller’s website, to report the total compensation of Huntington Beach employees – without including the payment on the unfunded liability:

If you’re trying to decide if these levels of compensation are enough or too much, there’s a lot to juggle. One immediate and rather inexplicable observation, common to most cities, is that firefighters are making more than police. Why is this, when there are perennial challenges to recruit police, whereas firefighting positions invariably attract hundreds if not thousands of applicants every time there is an open position?

Another puzzling fact that falls out of this pay schedule is the apparent affordability of pensions. This is grossly deceptive. “Normal” costs for pensions, as displayed on this table, average no more than the cost for health benefits. These misleading numbers underscore the deplorable state of pension fund management over the past 20 years, because most of the money being sent to CalPERS by Huntington Beach, and every other participating agency, is to pay down the unfunded liability. And the reason the unfunded liability is so huge is because the “normal” contribution has never been adequate. It certainly isn’t adequate now, but it obviously never was.

Political Pressure to Understate the “Normal” Cost for Pensions

Explaining this requires a careful balancing of nerd arcana with justifiable outrage. Enough arcana to make explicit what’s happened, enough outrage to make explicit just how much it matters.

Here goes: The “normal” contribution is how much money has to be invested per year in order to pay – after earning interest for years – for that additional bit of retirement pay that was earned in that year. For those who are still reading, here’s the kicker: The higher the percentage CalPERS predicts it can earn on its investments each year, the lower the “normal” contribution. Unfortunately, this rate-of-return projection is under extreme political pressure to remain higher than what history has demonstrated to be realistic. Recent events cruelly emphasize that historical lesson.

But if the rate-of-return is high and the normal contribution is low, then employees don’t have to contribute as much to their pension plans via withholding. And participating agencies, such as Huntington Beach, don’t have to pay as much into the pension funds. By falsely making them appear to be more affordable than they really are, it makes it politically easier to maintain, or even increase, pension benefits.

At this point, the story goes further downhill. As the normal contributions fell short, year after year, cities and other agencies participating in the CalPERS system played fast and loose with their repayment plans on the growing unfunded liability. Like the negative amortization mortgages that came due with a bang back in 2009 and 2010, eventually that house of cards collapses. Hence, a few years ago, CalPERS finally cracked the whip, requiring cities to pay down their unfunded liability on 20 year terms with level payments.

Readers who have a life may be forgiven for skimming the last three paragraphs, and may be commended if they are still reading at all. Here’s the bottom line: According to data straight from CalPERS, Huntington Beach taxpayers in 2019-20 will pay $14.7 million for the “normal cost” of their employee pension benefits. They will pay $29.9 million in catch-up money, aimed at paying down the unfunded liability for their pensions, twice as much as the normal cost.

When calculating an employee’s total compensation, clearly the cost of catch-up payments to bring a pension system back from 65 percent funded to fully funded belongs somewhere. To argue otherwise invites the suggestion that unfunded payments cease, and instead pension benefits become resized downwards, dramatically downwards, since that rather draconian measure would also serve to restore fully funded status to the system.

The rejoinder to this argument (hardened nerds, pay attention here) is that already retired workers also depend on the paydown of the unfunded liability, and the cost to sustain their pensions should not be included in any allocation of unfunded costs to active employees. With that in mind, even just allocating half of 2018-19’s $24.9 million unfunded pension contribution to the total compensation of active Huntington Beach’s employees yields a significant increase as follows:

On a pro-rata basis, this calculation increases the citywide average (using just half the unfunded payment) cost from $14,851 per full time employee to $28,532. Pension costs per police move from an average of $18,078 to $35,584, for firefighters from $23,367 to $45,995. In terms of total compensation, on this basis, the citywide average rises from $151,500 to $165,181; the police average rises from $164,457 to $183,074; the firefighter average rises from $204,064 to $227,065.

Huntington Beach’s Action Must Not Set a Precedent

It was hard to listen to the Huntington Beach city council members as they explained their reasoning prior to their voting, and not wonder what influences worked on them beyond the implacable reality of an insatiable pension system and a global economy that’s hit the pause button. To be sure, there had been prior discussions and agreements made, and one may argue this vote was a mere formality, ratifying compromises that were already well settled. But that’s a rather thin argument. When the Titanic hit an iceberg, did the Captain change his evening schedule?

The biggest problem with what Huntington Beach councilmembers did is the precedent it sets. The city faces a financial calamity, and avoiding $5.0 million more in expenses over the next three years will not change much. But what is needed now, in every city in California, is a freeze on compensation, among other things. It is virtuous and necessary to hope the economic meltdown that’s happening before our eyes will be overcome, and an economic recovery will soon take hold and sweep away our financial anxieties. But until that time comes, local elected officials have to stand firm. Unless things change, tough times are ahead.

Even harder are what must be asked of the public sector union leadership and members at a time like this. The reason public safety employees make more than they ever did historically is because as a society we value life more than we ever have in history. When we hire people to risk their own lives to protect us, we pay them very well because their lives, and our lives, matter more. That’s fine. But this pandemic is the reason we pay public safety employees so much money already. It is not the reason to pay them more, even though it certainly is the reason we appreciate them more than ever.

This article originally appeared on the website California Globe.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!