California Voters Approve Billions in Local Taxes and Borrowing

In March 2020, for the first time in a generation, Californian’s did not approve the overwhelming majority of new tax and bond proposals that were put before them. Out of 125 proposed local bonds, only 31 percent passed; out of 111 proposed local tax increases, only 41 percent passed.

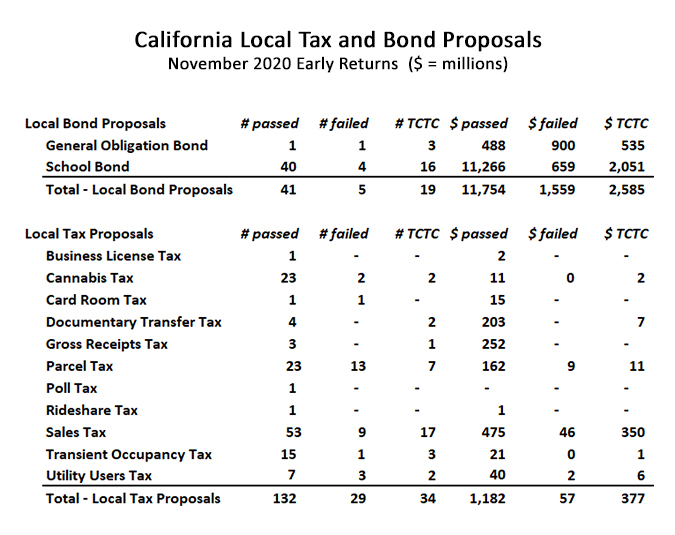

Early returns from the November 2020 ballot show Californians have snapped back towards approving the vast majority of new local taxes and borrowing. As shown on the table below, of the 46 proposals to issue new bonds that have been decided so far, 89 percent passed, and of the 161 proposals to raise local taxes that have already been decided, 82 percent passed.

Apparently the strong rebuke voters sent the borrow and tax lobby in March 2020 was a blip. The reasons people vote for new local taxes and borrowing are known: it’s for the children, it’s for the seniors, it’s for safety. The mystery isn’t why new local taxes and bonds are approved in overwhelming percentages by California’s voters. The mystery is whatever happened in March 2020 to dissuade them.

This November, along with the perennial appeals to voter concern for children, seniors and public safety, add the massive boost to targeted ballot harvesting facilitated by universal mail-in ballots, and probably a general recognition that the COVID shutdown has left public budgets a mess, which indeed it has. But what was it back in March 2020 that had voters turning down 7 out of 10 new bond proposals, and 6 out of 10 new tax proposals? What happened?

One possible explanation for the California electorate’s ephemeral rejection of more taxes and borrowing would be their dawning recognition of two simple facts: First, Californians suffer under the highest taxes and most crushing regulatory burden of any state in America. Two, California’s public employees are among the highest paid in America. Summarizing data from three recent reports on public sector compensation in California’s cities, counties, and state agencies, the following chart shows just how much California’s public servants made in 2019:

These averages, some of which are quite stupefying, understate what public employees make in California. Missing from these numbers are the costs of properly funding retirement pensions, as well as the costs of prefunding retirement health insurance. Increase everything by around $10,000 per year to get closer to the true value of a job in public service.

Critics of compilations such as these point to the risks taken by members of public safety, or the higher than average educations required to work as a government bureaucrat. These criticisms are valid, but miss the point. The unions that “negotiated” these stupefying compensation packages with the politicians whose campaigns they funded are also able to exercise almost absolute control over what laws are passed by the state legislature, and what regulations are written and implemented by state agencies. And is the policies, union approved, enforced by California’s state and local governments, that have led to California having a punitively high cost-of-living.

It is in these unions own interest to fix this. Sooner or later – and with the COVID shutdown, sooner is here – these crippling regulations, staggering debt, and absurdly high taxes are going to throw California’s economy into a tailspin. And when that happens, and for a change, it won’t just be the vanishing middle class that suffers.

California’s economy is big and diverse. It will always bounce back. But California’s prosperity would be more evenly distributed without union inspired redistribution schemes and regulatory entanglements. The unions that run California not only need to recognize that deregulation and competition are the best ways to ensure their members continue to enjoy generous pay and benefits, but that only they have the political power to make that happen.

Someday, when things get back to normal, post-COVID, California’s voters may decide they’ve had enough of high taxes, crippling regulations, and public employees that make far, far more than the average private sector worker. They proved they still have it in them to do that, back in March 2020, before everything changed.

This article originally appeared in the California Globe.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!