Are Government Pensions Funds in Crisis Again?

If ever there were a case of Chicken Little, it’s the endless squawking over the imminent implosion of public employee pension funds. In California, ever since pension benefits were enhanced, retroactively, starting in 1999, critics have been claiming a pension apocalypse was imminent. But no matter what happens, pension funds muddle through.

The modern era of pensions began in the 1984, when pension system guidelines were revised to permit them to purchase equities without limit. By 1999, on the strength of a nearly 15 year run of unbroken equities growth, California’s pension systems were fully funded with surpluses. With their confidence undiminished after the internet bubble popped and stocks tanked, pension system managers blithely continued to advocate pension benefit enhancements. By 2005 those benefit enhancements had rolled through every agency in California, and by then the markets were recovering as well. Then came the crash in the fall of 2008. To cope, the pension systems began to use creative accounting. Collectively these gimmicks obscured growing problems.

For example, asset “smoothing” made it possible to hide recent drops in the value of invested assets by reporting the average value of those assets over previous years. As the funded status – the difference between total invested assets and the amount the fund actually needs to pay current and future pensions – worsened, pension systems began to require so-called “unfunded contributions,” which were catch up payments necessary to reduce the growing amount of underfunding. But by negotiating repayment terms analogous to negative amortization mortgages, agencies were allowed to make low payments in the early years of the amortization term, which frequently meant the underfunded amount wasn’t even being reduced. Then when those payments become burdensome, agencies would refinance the new, now even larger unfunded liability, to get that unfunded payment down again.

Gimmicks abounded. Pension funds in the early 2000s used an estimated rate-of-return per year of around 7.0 percent, which was obviously too high, since the funding status of pension systems continued to worsen. But by maintaining the fiction of a higher than realistic rate-of-return, pension systems could underestimate the size of their pension liability, and claim there was enough money in the system. If they acknowledged that returns might be lower, they would need more assets to make up the difference.

The consequence of this was pension systems quietly ended up with an unfunded payment that came to dwarf the “normal” payment. If a pension system is fully funded, the only contribution required each year is the “normal” payment, which is the amount of money that has to be invested in order to pay whatever amount of future pension benefits were earned in that year. This is the essence of pension finance. You estimate the present value of future pension benefits, and make sure you have that amount invested today. When you don’t do that, you end up with an unfunded liability. In California today, in almost every one of the pension systems set up for government retirees, the unfunded payment that agencies have to make to the pension systems is now more than the normal payment. But guess what? The only portion that public employees have to themselves help pay through payroll withholding is the normal payment. Taxpayers pick up everything else.

If all this complexity is tedious, join the club. An innumerate legislature, a powerful public employee union lobby, and inadequate pension system oversight has put us where we are today. Pension systems that remain only 70 percent funded, with taxpayers footing far more than their share.

So are we today at just another Chicken Little moment? After all, the pension systems have bent but they never broke. This is thanks to the PEPRA reforms of 2013, the GASB reforms of 2015, along with agencies picking up unfunded contributions that slowly grew into the monster they are today, which allowed them time to raise taxes and cut services so they could make those higher payments.

Taking all this into account, it is not unreasonable to consider government pensions resilient enough to take whatever is coming next. Nonetheless, with today’s uncertain outlook for stocks, bonds, and real estate, it is timely to have another look at the financial health of California’s pension systems. Since CalPERS is the 800 pound gorilla in California’s pension jungle, a look at its finances may be illustrative.

The first chart shows the funding status of CalPERS by year, starting with the fiscal year ended 6/30/2007 and continuing through 6/30/2020, the most recent year for which financial statements are available. As can be seen, CalPERS has only been around 70 percent funded for over six years. It is also evident that 2013 was a pivotal year for the fund, because in that year, the value of the total invested assets actually declined, from $283 billion on 6/30/2012 down to $281 billion on 6/30/2013. The funded ratio prior to 2013 had stayed over 80 percent, but subsequently fell down into the 70s and still has not recovered. Something else that should be noted from this first chart is the relentless growth of the pension liability. Between 2012 and 2013, as total investment assets shrunk in value, the present value of future pensions increased by over 10 percent, from $340 billion to $375 billion. Overall, during the 14 years reported here, while assets increased in value by 181 percent, liabilities increased by 223 percent. The combination of absolute growth in the total pension liability and a diminishing funded ratio has a compounding impact on the amount of the unfunded liability. As of 6/30/2020, CalPERS was facing an unfunded liability of $163 billion. Taxpayers are on the hook for 100 percent of this debt.

Something else that should be noted from this first chart is the relentless growth of the pension liability. Between 2012 and 2013, as total investment assets shrunk in value, the present value of future pensions increased by over 10 percent, from $340 billion to $375 billion. Overall, during the 14 years reported here, while assets increased in value by 181 percent, liabilities increased by 223 percent. The combination of absolute growth in the total pension liability and a diminishing funded ratio has a compounding impact on the amount of the unfunded liability. As of 6/30/2020, CalPERS was facing an unfunded liability of $163 billion. Taxpayers are on the hook for 100 percent of this debt.

While complete financial statements for CalPERS – and most public employee pension systems – lag about 18 months behind their close dates, every month CalPERS offers an update on the value of their invested assets. Reviewing the latest available report reveals the risks they have begun to take in order to prevent their funded ratio from further deteriorating.

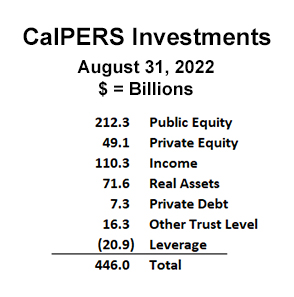

The next chart, below, provides a snapshot of CalPERS investments as of August 31, 2022. Their total assets have swollen to $446 billion. That’s good performance, implying an annualized return over the 14 months since 6/30/2020 of over 9 percent. But what’s in these numbers? Here is where CalPERS position may be more precarious than ever. Consider each category of assets, including some you would not have spotted ten years ago. Public equity refers to listed stocks, and with the market in turmoil, the direction of these investments is uncertain. “Income” refers mostly to bonds with fixed yields, and as interest rates go up, the value of previously purchased bonds must fall, since for them to remain marketable the yield from their fixed payment has to rise to a competitive level. “Real assets” refers to real estate investments, which, like publicly traded stocks, is in uncertain territory. But what about the other categories?

Here is where CalPERS position may be more precarious than ever. Consider each category of assets, including some you would not have spotted ten years ago. Public equity refers to listed stocks, and with the market in turmoil, the direction of these investments is uncertain. “Income” refers mostly to bonds with fixed yields, and as interest rates go up, the value of previously purchased bonds must fall, since for them to remain marketable the yield from their fixed payment has to rise to a competitive level. “Real assets” refers to real estate investments, which, like publicly traded stocks, is in uncertain territory. But what about the other categories?

Here is where even greater risk to the CalPERS investments may reside. Private equity and private debt refer to investments in companies that are not yet listed. These investments lack the liquidity of publicly traded stocks and bonds, and the financials of these companies are not as transparent. Private equity may also include hedge fund investments which are even more volatile.

And then there is “Other Trust Level” investments, where CalPERS has deigned to commit over $16 billion. In the footnotes to CalPERS Trust Level Quarterly Update, decipher this description: “Trust Level Financing reflects derivatives financing and repo borrowing in trust level Synthetic Cap Weighted and Synthetic Treasury portfolios.” Good luck with that. This is pre-financial crisis speculative behavior, the sort that almost brought down the entire financial system. To further put this in context, “Leverage” refers to money CalPERS borrowed in order to make additional investments, hoping those investments would earn more than they paid to borrow the money.

A financial blogger operating under the pseudonym “QTR” (Quoth the Raven), with thousands of subscribers on Substack, warned last week what could happen to U.S. pension funds, writing “The fact that these funds were unable to post the returns that they needed during arguably the most euphoric bull market in history is extremely concerning.”

If CalPERS is any example, indeed they could not. During the period from 2007 t0 2020, CalPERS went from 87 percent funded to 70 percent funded. Because annual pension benefit payments to government retirees in California are required to match inflation once the purchasing value of a pension falls to within 75-80 percent of its purchasing power upon retirement, inflation is going to drive the amount of the total pension liability up faster than the 6.4 percent it averaged over the past 14 years. CalPERS, and the other pension plans, are chasing a greyhound, and the engine is overheating.

California’s pension systems, to the extent they have matched CalPERS in diverting billions of dollars into private debt and equity, hedge funds, derivatives, and other highly speculative financial instruments, and financed these adventures with borrowed money, are stretched as far as they can go. California’s legislature needs to investigate the asset mix of state and local government pension systems and honestly appraise the exposure. Are they facing margin calls? Do they face liquidity risk?

As for the financial experts running California’s pension systems, they need to back away from speculative investments, deleverage, and tell the union lobbyists and their captive legislators the truth: We can no longer use creative accounting and high-risk investment strategies to perpetuate the perception of system stability.

This article originally appeared in the California Globe.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!