California’s total state and local government debt now stands at almost $1.6 trillion, or about half the state’s GDP.

That isn’t an alarming ratio when compared to the national debt, which has now soared to 128 percent of U.S. GDP with no end in sight. But Californians carry this $1.6 trillion state and local debt ($40,000 per capita) in addition to their share of the national debt (about $90,000 per capita).

Consolidated data on state and local debt is maddeningly difficult to compile. Getting the most recent data for California’s state and local bond debt requires downloading and analyzing the publicly released annual financial reports for 58 counties, 481 cities, 1,037 school districts, and 3,400 special districts. And even if data miners were to apply sweat and algorithms to this chore, at this moment in early 2022 the complete dataset can be obtained only for the fiscal year through June 30, 2020.

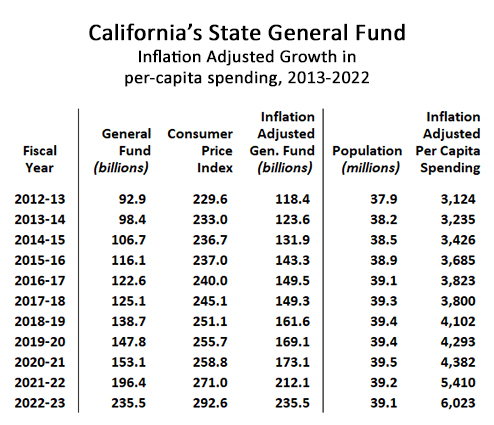

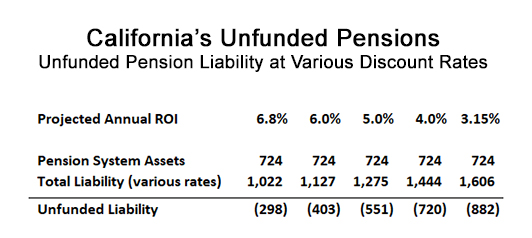

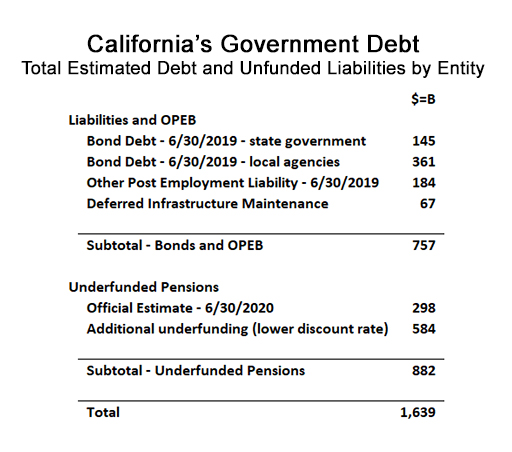

Rather than engage in a from-the-ground-up exercise in data gathering, we have turned to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 “State & Local Government Finance Historical Datasets and Tables,” which is the Bureau’s most recent compilation. According to the Census Bureau, California’s total state long-term debt was $145 billion at the end of 2019, and California’s total local debt was $361 billion. This total, $506 billion, passes the sanity check when compared to the 2017 state/local debt estimate we compiled a few years ago, $482 billion. The slight upward trend comports well with the probability that newly issued bonds each year will marginally exceed the amount by which existing bonds are paid down or retired.

Another significant source of state and local debt is Other Post Employment Benefits, or “OPEB,” which refers to financial obligations that agencies have for current and future retirees, primarily for health insurance. Based on a 2021 study by the Reason Foundation‘s Marc Joffe, we report that California’s state and local agencies have a cumulative OPEB liability of $184 billion.

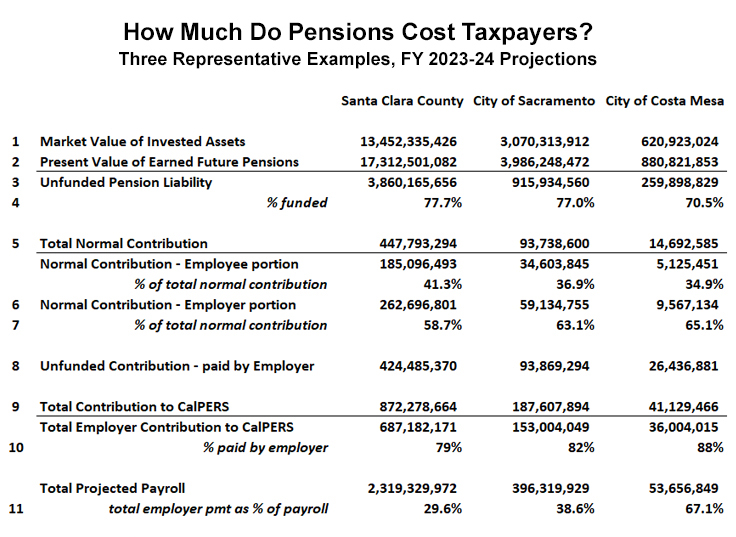

But OPEB, by virtue of being “other” post employment benefits, does not include the elephant in the room, pensions. California’s State Controller provides comprehensive data on state and local government pension obligations on their “By the Numbers” website. From this downloadable data, updated through June 30, 2020, we are able to calculate the officially recognized unfunded pension liability, which is the amount by which the current value of invested pension fund assets do not equal the present value of pensions to be paid to current and future retirees. The Controller calculates that deficit at $298 billion, but we believe that’s overly optimistic. We believe the official estimate falls $584 billion short of what will actually be required to pay these pensions. The result: we estimate California’s state and local governments owe the pension system $882 billion.

Clearly, such an estimate merits a more lengthy discussion, which will follow. Also to be discussed is California’s deferred infrastructure maintenance, a liability which according to the California Office of Legislative Analyst is now $67 billion. Depicted below is a chart that summarizes our estimate of California’s total state and local government debt:

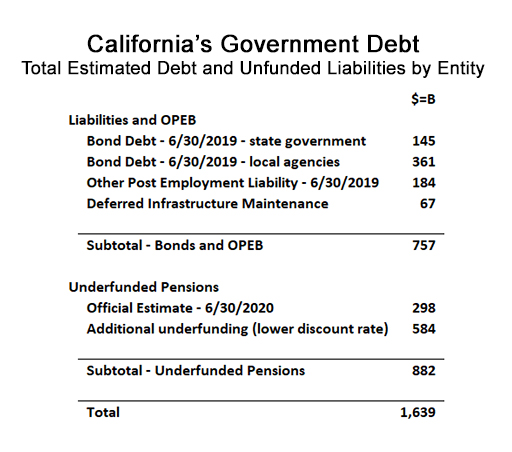

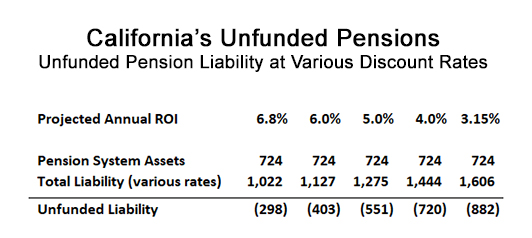

In 2012, Moody’s Investors Service revised its method of valuing pension liabilities, with the principal adjustment being what discount rate to use when calculating the present value of projected future pension payments to retirees. The lower the discount rate used, the higher the present value. Moody’s now recommends using the high-grade long-term corporate bond index discount rate, which today is pegged at 3.15 percent. By contrast, California’s state and local government pension systems currently calculate the present value of their future pension payments (“Total Liability”) by applying the annual rate-of-return at which they expect their assets to appreciate. For CalPERS, California’s largest pension system, that rate is currently set at 6.8 percent.

The difference between using a rate of 6.8 percent vs 3.15 percent to calculate the present value of future payment obligations is shown on the next chart. It’s not subtle.

As you can see on row two, “Total Liability (various rates)” increases as the projected annual return-on-investment is reduced. And the bigger the liability, the bigger the shortfall between the Pension System Assets and the amount they need to cover. Hence the unfunded liability grows as the amount a pension system thinks it can earn each year shrinks. The column to the far left reflects the official estimate, $298 billion, for California’s total state and local agency unfunded pension liability. The column on the far right reflects that same liability based on the much lower 3.15 percent rate used by Moody’s Investor Services, $882 billion. The intermediate columns reflect the amount of the unfunded pension liability at rates in between these two extremes, 6.0 percent, 5.0 percent, and 4.0 percent.

Given the size of these numbers, and the dire financial consequences of getting the projections wrong, the controversy over which percentage to use is probably the most consequential public debate that nobody has ever heard of. Stanford economist Joshua Rauh argues that pension liabilities should be discounted by the risk-free rate because they are virtually certain to be paid. In a 2019 study, he used 2.5 percent, based on the historical volatility of equity investments.

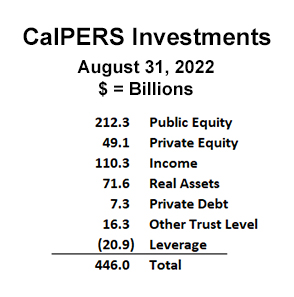

We can only really know the right discount rate in hindsight, of course, and in hindsight one might argue that over the past 20 years the results are reassuring. As noted on the “Returns Tracker” maintained by the trade publication Pensions and Investments, the 20-year average return for CalPERS was 6.9 percent, and for the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) it was 7.6 percent. California’s other smaller government agency pension funds have generally produced similar results.

Do these encouraging returns over the past 20 years justify complacency? That’s tough to say, but before dismissing concerns about their future it’s fair to wonder how the pension systems dug themselves into a hole that is, by the most generous analysis, nevertheless at least $298 billion dollars deep.

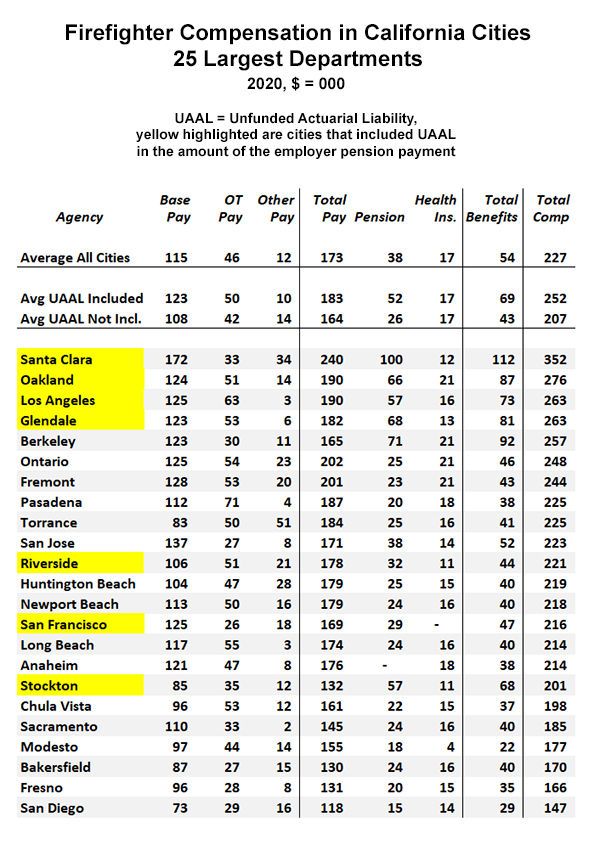

You can find a summary of some of the events leading to such a state of affairs in a 2018 California Policy Center report “Did CalPERS use accounting ‘gimmicks’ to enable financially unsustainable pensions.” The Cliffs Notes version: They did. At the turn of the century, on the basis of optimistic projections and creative accounting – and egged on by government union leaders – CalPERS management sold local and state elected officials on a scheme to bump most pension benefits by 50 percent, with retroactive effect. The rest of California’s government pension systems quickly followed suit. With technology stocks driving a fantastic bull market in the 1990s, nobody thought anything could possibly go wrong. But after the October 2008 crash, pension funds found themselves demanding higher and higher payments from government payroll departments, a trend that continues to this day.

While Governor Jerry Brown’s Public Employee Pension Reform Act (“PEPRA”) of 2013 has begun to take some financial pressure off the pension systems, they are in no position to handle another crash. Even today, following a remarkable 10-year technology-driven bull market, the pension systems acknowledge they’re only 71 percent funded. If history repeats itself, the funds – and the California taxpayers responsible for them – are in for a shock.

As it is, in 2020, using data provided by the State Controller, California’s state and local governments contributed $46 billion to the pensions systems; through withholding, government employees contributed another $15 billion. This total, $61 billion, exceeds the amount realized through returns on pension system assets in 2020, which was only $42 billion. From a related angle, California’s public retirement systems paid out $65 billion in pension benefits in 2020, while collecting $60 billion in contributions. It was never the intention of the pension systems to be requiring agencies to pay in as much each year as the systems were paying out in benefits.

To illustrate how this misleading claim – that investment returns would be the primary source of pension system funding – was used to justify increasing pension benefits, and is currently used to prevent further reform, consider this “Myths and Facts” webpage, paid for by California’s government unions. In a document replete with selective use of facts and data, this stands out: “According to the latest data, CalSTRS employers, including the state, contribute 25 cents of every pension dollar paid.” This is clearly false. According to the State Controller, as we have seen, when $65 billion in pension benefits was paid out in 2020, $42 billion was paid into the pension systems by government employers. That’s 65 percent, not 25 percent.

How Will Inflation Affect California’s Pensions?

At first glance, the fact that pension systems put a cap on their annual cost of living adjustment (“COLA”) – this varies but typically does not exceed three percent – might suggest that another paroxysm of multi-year inflation would be at least restore pension solvency. One could reasonably assume that if growth of the liability is capped at around three percent per year, while annual contributions to the pension systems rise because they’re being withheld from payrolls that driven higher by cost-of-living adjustments pegged to inflation well in excess of three percent, then the unfunded liability will wither away. But that reasoning is flawed. The way pensions are structured in California, if there is a sustained bout of high inflation, the cap is uncapped.

For better or for worse, all pension systems guarantee retirees a purchasing power “protection allowance” of 75 to 80 percent, meaning that inflation cannot erode the value of a pension payment below that threshold. This means the cost-of-living adjustments, once pension payments hit that floor, will have no ceiling. The question then becomes whether real rates of return (nominal rate of return less the rate of inflation) will be sufficient to fund pension systems that have hedged their beneficiaries against inflation during a period of high single digit or even double-digit inflation. Nobody knows how that is going to turn out, but if real returns falter, agency contributions will have to pick up the slack. It could be a lot of slack.

What this really comes down to is the so-called real rate of return that a pension system can earn. This refers to the nominal performance of the fund, which in CalPERS’ case has averaged 6.9 percent over the past 20 years through 2020, minus the rate of inflation. CalPERS actuaries, when projecting the system’s future pension liability, currently use an inflation assumption of 2.5 percent per year. This means they currently assume their real rate of return to be 4.4 percent.

This is the context in which to view pension fund performance in excess of, in the case of CalPERS, for example, 6.9 percent. That target is misleading and insufficient when inflation is greater than 2.5 percent per year. As the purchasing-power protection allowance kicks in for retiree after retiree in system after system, just to stay even, a pension system such as CalPERS needs its annual return on invested assets to achieve returns that are 4.4 percent above the rate of inflation. If inflation is seven percent, as just reported by the U.S. Dept. of Labor for the 12-month period through January 2022, then just to stay even, CalPERS would need to turn in an investment performance of 11.4 percent.

Pension systems in California have not experienced significant inflation over the past 20 years, which is the period during which they have been coping with the impact of the benefit enhancements awarded around the turn of the century. During the inflationary era 1973 to 1981, stock indexes were negative in nominal terms. This exemplifies the volatility of investment returns and lends credence to conservative analysts such as Stanford economist Joshua Rauh urging actuaries to use even lower discount rates than Moody’s has applied.

Volatility Defines California’s Public Finances

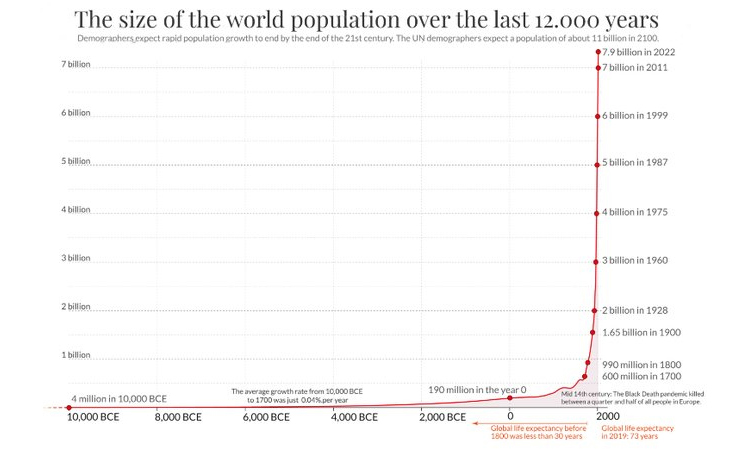

In addition to investment performance and background inflation, the financial health of pension funds is highly sensitive to life expectancy and the ability of agencies to pay the required annual contributions. That’s just a very big and very representative subset of the financial challenges facing all public agencies in California.

There are other challenges. California’s state tax revenues are inordinately dependent on high-wage earners, as documented here, here, and here. In turn, those high-wage earners are reaping windfalls during tech booms. But booms are by definition cyclical, and when the tech boom busts, not only do state income tax revenues plummet, but the tech-driven investment returns of the pension funds falter at the same time. The financial status of California’s pension funds may not be truly alarming today – 71 percent funded is not “alarming,” but it’s far from “excellent” – and the vaunted surpluses in the state budget, swollen with slices of tech-baron bounty and billions fresh off federal printing presses, may suggest a rosy future. But when the economic pendulum swings back the other way, state and local government agencies will face unprecedented budget deficits – at precisely the same time the pension systems are demanding increased contributions from state and local governments.

SOLUTIONS

To restore stability to the system, pension reform must be part of a broader package of policy shifts. For government workers to be able to financially tolerate lower pension benefits, the cost of living in California has to become competitive with other states. This will require business deregulation, which is contrary to everything California’s legislature has worked toward over the past few decades.

The state could also lower California’s cost-of-living by investing in so-called “good debt,” that is, projects that yield long-term economic benefits. Water infrastructure is a prime example. If the state upgraded California’s water system to 21st century standards to create a surplus of water at an affordable price to consumers, it would make it possible to build new homes – homes that cannot get permits without a reliable water supply. It would enable California’s agricultural industry to produce vegetables and dairy products at lower prices. It would make it possible for businesses that use water to offer their products and services at affordable rates and still make a profit. And it would make water utility bills affordable to low-income households.

The California Office of Legislative Analyst estimates just to complete the deferred maintenance of public infrastructure in the state would cost $67 billion. This of course merely scratches the surface of what is needed, since the LAO’s narrow definition of deferred maintenance refers to the backlog of maintenance work required on existing infrastructure, not the infrastructure we need today, and should have been building for the past few decades. To create the economic prosperity and lower cost of living that would permit more cost-effective government and right-sized pension benefits, investment in new public infrastructure is required. And to state the obvious, High Speed Rail does not qualify. High Speed Rail epitomizes bad public infrastructure investment and bad debt, because it will constitute a permanent economic drain.

A discussion of what public infrastructure exists in California, vs. what public infrastructure ought to exist by now, is beyond the scope of this analysis of the total state and local debt that confront California’s taxpayers. But just like pensions, when insufficient investment is made on an ongoing basis, the financial obligation builds up and its burden falls on future generations. And unlike pensions, which can be right sized, or restored to solvency every time there is a capricious bump in the value of the invested assets of the pension systems, the only cure for neglected infrastructure is to either commit to massive new spending, or submit citizens to rationing and high prices for every basic necessity – transportation, housing, energy, and water. For the time being, California’s policymakers are firmly committed to the latter.

For this reason, one might argue California’s true debt overhang is not the officially recognized $1.0 trillion, or even the $1.6 trillion (or more) that accrues if pension analysts use more prudent financial assumptions when calculating the unfunded liability. Taking into account the cost for the public infrastructure that Californians deserve, and that should have been built by now, it is reasonable to assume California’s state and local public debt exceeds $2.0 trillion.

Whether it’s one trillion or two trillion, California’s total state and local government debt, given the size of its economy, may still not be unmanageable at the moment. But the choices California’s legislators and pension boards make over the next few years will determine whether a truly devastating financial and economic crisis materializes or, instead, government agency balance sheets acquire the resilience necessary to cope with the economic turbulence that could lie just ahead.

An edited version of this article appeared on the website of the California Policy Center.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.