Environmentalists in California, who constitute much of the vanguard of environmentalism in the world, have normalized extremism. The solutions they’ve proposed to supposedly save the planet, and the premises they’ve convinced millions of people to accept as beyond debate, constitute one of the greatest threats – if not the greatest threat – to modern civilization today. It is these environmentalists that are themselves the extremists, not the common sense skeptics who question their edicts, or the beleaguered citizens trying to survive their mandates.

The power of the environmentalist juggernaut, or, to be more precise, what has become an environmentalist industrial complex, almost defies description. Their grip on the media, as we have seen in the previous installment, is near absolute. They exercise similar control over how American children are educated in K-12 public schools, as well as what messages are reinforced in almost every institution of higher learning. They have coopted nearly every major corporation, investment bank, hedge fund, sovereign wealth fund, and international institution including the World Bank, the United Nations, and countless others. From every source, the message is always the same: We face imminent doom if we don’t take dramatic collective action immediately to cope with the “climate emergency.”

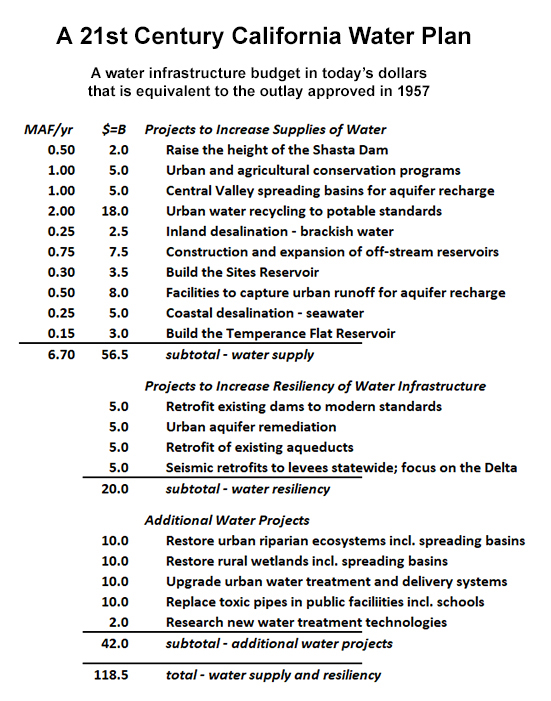

The good news is that if you want to build more water infrastructure in California, you don’t have to argue the intricacies of climate science. If the Sierra snowpack is to be permanently reduced if not nonexistent, and if all we can expect in a drier future are occasional and erratic but soaking downpours, then we have to build a new water infrastructure that is adapted to this new reality. But despite this logic, environmentalists seem to oppose all new water infrastructure, everywhere. Their endless opposition to the Sites Reservoir, which is designed to capture storm runoff and store it off-stream, ought to be inexplicable. It can only be understood in the context of their broader agenda, which in practice amounts to micromanaging residential indoor water consumption, mandating desert landscaping around homes, and taking half of California’s farmland out of production.

A front page article in the Los Angeles Times on April 13, 2022, written by Ian James, is a recent and very typical example of what environmentalists are planning for California. In the article, titled “California could shrink water use in cities by 30% or more, study finds,” environmentalist spokespersons are quoted with no tough questions asked or balancing perspective solicited. The crux of the study’s findings amounted to this:

“The state’s total urban water use is estimated at 6.6 million acre-feet per year [this does not square with the estimates from the California Dept. of Water Resources, which report average urban use at 7.8 MAF/year]. The study found that a host of existing technologies and standard practices could improve efficiency to reduce total urban use between 30% and 48%. These efficiency measures include fixing leaks in water pipes, replacing inefficient washing machines and toilets, and replacing lawns with plants suited to California’s dry climate, among other things.”

Imagine that. Cutting water use by 48 percent. Forty eight percent. Why would anyone want to do this, when there alternatives?

James’s article is worth examining in some depth, because it reveals additional claims from the Pacific Institute study, entitled “Waste Not, Want Not: The Potential for Urban Conservation in California,” that belie the need to curtail urban water use so drastically. In particular, it makes the following claims:

“The researchers estimated that California has the potential to substantially boost local water supplies by capturing stormwater and storing it in aquifers, instead of allowing it to run off the landscape. Depending on whether it’s a dry year or a wet year, they said, the state could capture between 580,000 and 3 million acre-feet of stormwater in urban areas.”

And…

“California now recycles about 23% of its municipal wastewater, an estimated 728,000 acre-feet, the report said, and has the potential to more than triple the amount that is recycled and reused.”

What this study therefore claims is that just by capturing regional stormwater and recycling wastewater, California’s urban areas can recover and use between 2.0 million and 4.5 million acre feet of additional water per year, meaning their net water consumption, i.e., the amount of water they are going to need from existing sources can drop from – using their numbers – 6.6 million acre feet per year down to between 2.1 and 4.6 million acre feet per year.

First of all, that ought to be plenty, although it would be interesting to find out if the Pacific Institute researchers actually had a serious discussion with any if the engineers at the urban water agencies and flood control districts that would have to figure out how, for example, to grab five inches of torrential rains hitting the Los Angeles Basin in 12 hours and get all of that runoff into an aquifer or reservoir before it made the at most 30 mile trip from the base of the San Gabriel Mountains to the Santa Monica Bay. We’d be all for that, if it were feasible. But maybe the feasibility wasn’t the point; maybe the Pacific Institute wanted to publicize these figures to help opponents of the proposed Sites Reservoir and Huntington Beach desalination plant. After all, who needs off-stream reservoirs or desalination, if we can just capture urban storm runoff?

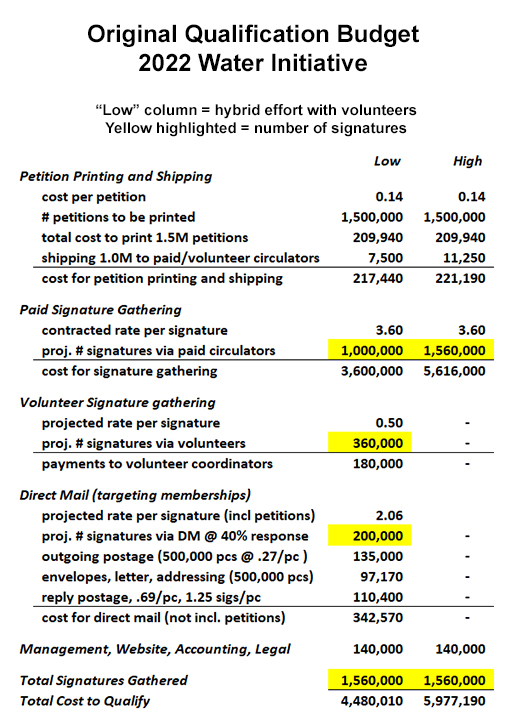

More to the point, funding runoff capture and funding wastewater recycling were among the centerpieces of our proposed water initiative! And we left it up to the water commission to decide which project applications to fund, only stipulating that funding would not dry up until five million acre feet of new water could be supplied each year. The Pacific Institute, an organization as environmentalist as they come, has just provided a roadmap to finding up to 4.6 million acre feet of that annual goal, if their findings are to be believed.

Nonetheless, the title and the focus of the article in the Los Angeles Times, indeed, the focus of every policy most fervently supported by environmentalists in California today, is use less. Conserve. Cut back. Ration. Take short showers. Kill your water wasting plants and replace them with desert scrub. Sacrifice. And none of it is necessary, either to save the planet or to save money. But that’s the message. That’s their agenda.

The way environmentalists attacked our attempt to qualify a water infrastructure spending initiative gave no quarter. Early in our campaign phase, barely after we’d submitted our final amended version of the initiative, the board of directors at the Orange County Water District were voting on a possible endorsement (they ultimately did vote to endorse). But already the Sierra Club was on hand to object, making claims that indicated they may not have even read the text of the initiative.

In their public comment, made October 6, 2021, they wrote “OCWD would be best placed to funnel its resources towards increasing conservation, stormwater capture, implementing a green streets project similar to LA County’s, repairing leaks and replacing old pipes, earthquake proofing its water systems and remediation of its North plume including other PFAS contaminated wells.”

The problem with these arguments against our effort, to reiterate, is that our measure would fund all of those suggestions. They all would have qualified as eligible projects to be evaluated by the California Water Commission. All the environmentalists critics of our initiative needed to do was read Section 3, starting on page 2 of the full text, items 1-7. It’s all there. Our five million acre foot per year goal – which one may argue that even the Pacific Institute implicitly supports – was only the trigger to end funding. It did not limit eligible project categories only to those that would further achievement of the 5 MAF/year goal. Everything the Sierra Club was suggesting ought to be in the initiative, was in the initiative.

None of these facts mattered. Including the forbidden solutions of reservoirs and desalination were unforgiveable sins. Within a few months, the environmentalist opposition had coalesced into a coalition that included the following groups: Sierra Club California, California Indian Environmental Alliance, Society of Native Nations, Idle No More, Restore the Delta, Azul, Golden State Salmon Association, Sunrise Movement OC, California Coastal Protection Network, Health the Bay, Surfrider Foundation, Los Angeles Waterkeeper, Orange County Coastkeeper, The River Project, Heal the Bay, and Social Eco Education.

On a website called StopTheWaterScam.com, funded by the “Stop the Water Scam Committee (ID# 1442883),” some amazingly misleading representations were made. On their home page, our initiative was depicted as “a new threat to literally every priority California faces, from public health to education to affordable housing to climate action.” On the website’s “FAQ” page, they made the following claim about our alleged backing, writing “They’re financed by powerful multinational corporations and polluters who want a bottomless slush fund to profit at taxpayer expense.”

All of these are preposterous allegations. How is abundant water a threat to public health? If having a reliable water supply is a prerequisite for building new homes, how does our initiative threaten affordable housing? If climate change is causing less snow and more severe but erratic rainstorms, don’t we need new infrastructure to capture and store the runoff? And if we build infrastructure that makes more water available for farms and cities, then wouldn’t we also have more water available to manage ecosystems? As for “powerful multinational corporations” supposedly behind our effort; which ones? When? Where? Who?

The reasons environmentalists might have had more arguable objections to our initiative centered on the revisions it proposed to the California Environmental Quality Act and to the Coastal Act. But the revisions we made were thoughtful and measured. Virtually everyone we spoke with believed that without the proposed changes to these laws, the initiative would suffer the same fate as Prop. 1 from 2014 – a voter mandate that is stopped in its tracks by a hostile bureaucracy and environmentalist litigants.

What follows are some of the serious questions raised by environmentalists, and how we responded to those questions:

The initiative creates a mechanism to use public funds to subsidize private, for-profit enterprises such as Poseidon desal. Why should the public fund such a project when Poseidon has indicated they are able to proceed without additional subsidies (they are counting on an annual operating subsidy from the Metropolitan Water district)?

The California Water Commission will have the discretion to allocate funding to eligible projects according to a set of criteria and priorities set forth in the measure. Section 3 of the measure provides that projects proposed by public agencies should be prioritized. Thus, the ultimate funding decisions will be made by the Water Commission in accordance with the goal of the measure—completing projects to begin delivery of water to California’s urban and agricultural consumers. There is no guarantee that any private projects would receive funding under the measure. And if a project does not need funding, it will not get funding.

Why is the streamlining of environmental review necessary?

There is NO streamlining of CEQA proposed. Section 5 of the measure provides for streamlined review of judicial CEQA challenges to eligible water projects. Currently, important water projects can be and are stalled through litigation that can last for many years. Under the measure, any challenge to an eligible water supply project is to be resolved (e.g., decided by a court) within 270 days after the certified administrative record is filed with the court. This is substantially similar to previously adopted legislation including AB 900 and subsequent acts based on AB 900 (which expedited treatment of various projects—See the California Office of Planning and Research website), and various other statues providing for litigation streamlining (see also SB 9 Atkins – Jobs and Economic Improvement Through Environmental Leadership Act of 2021 -adopted this year). Water projects must still comply with ALL CEQA substantive reviews.

Specifically, why should the Coastal Commission rely on the EIR submitted to the lead agency without the ability to require “new or revised environmental review”? (First paragraph, p. 15).

First, the Coastal Commission is a responsible agency under CEQA and can fully participate in the CEQA process of any agency involved in a project in the Coastal zone. The Coastal Commission nearly always acts on a project after a local agency has completed a full CEQA review and approvals have been issued. The Coastal Commission then has a certified regulatory process that operates as a functional equivalent of CEQA. This provision would avoid delays associated with “re-creating the wheel” late in the permitting process.

Also, why should the secretary of natural resources’ override authority be applied retroactively?

This provision allows flexibility so that any project that receives funding or is certified as a drought resiliency project may be reviewed, without imposing an arbitrary deadline.

Coastal Commission Executive Director Jack Ainsworth said, ” “This is an insidious maneuver that could allow wealthy corporations to overturn Coastal Commission actions protecting California’s precious coastal resources, public access and coastal communities. Drought in California is our new normal and the Commission understands that responsibly designed desalination facilities will be an important part of California’s water portfolio going forward. We don’t need to gut the Coastal Act in order to provide safe, reliable, affordable drinking water.” Would you respond to that?

We view the Coastal Commission as playing an essential role in projects that are located along California’s coast. That is why Coastal Commission process is retained in the measure, rather than exempt water supply projects which are crucial to the State from Coastal Commission review entirely. The measure simply provides some timelines for the Commission to act on drought resiliency projects and clarifies the environmental review process before the Commission. The measure also provides for an administrative appeal process to the Secretary of Natural Resources. This is very similar to the appeals process within other agencies, such as the Regional Water Board, whose decisions can be appealed to the State Water Board.

What CEQA protections remain if eligible projects are “exempt from CEQA.” Is there a contradiction between what the campaign is saying about the CEQA provisions and what the CEQA provisions actually say? In the language of the initiative at the top of page 14, it says: “(b) Notwithstanding subdivision (a), the Water Commission’s determination to (1) allocate funding pursuant to Section 2.5 of Article X of the Constitution or the Water Supply Infrastructure Bond Act of 2022 or (2) certify a project as a drought resiliency project pursuant to Section 21159.52 shall not constitute a ‘project’ pursuant to Section 21065 of the Public Resources Code and shall be exempt from CEQA.” How does this initiative still incorporate “substantive CEQA review?”

The initiative does not exempt water supply projects from substantive CEQA review. The initiative exempts certain funding and certification processes at the Water Commission from CEQA review – namely, the Water Commissions’ decision to provide funding to an eligible water supply project or certify an eligible water supply project as a “drought resiliency project.” However, the initiative does not eliminate CEQA review triggered by other discretionary actions, such as local or state permitting processes. For example, a water supply project requiring a discretionary city or county approval would still undergo CEQA review in connection with that approval. As for “drought resiliency projects,” they are any projects that fall within the definition of eligible projects in Section 3 (b) on page 2.

If the California Water Commission were the only agency approving a project funded under this measure, then it would be exempt from CEQA, but if the project required other approvals, like from a city, a county, a regional water board, the state EPA or Department of Fish and Wildlife, it would be subject to CEQA?

Yes. If a project required a discretionary approval from any other agency, it would be subject to CEQA (unless some other CEQA exemption applied independent of the measure). The chances that a water supply project of any size would not require at least one additional discretionary approval is very remote. Virtually any project involving water resources will trigger a local review and a review from various state agencies including the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. For example, a water project impacting a stream or river would require permitting from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Can you explain the streamlining of filing lawsuits? It appears that after a project is approved, opponents have 270 days to file a lawsuit under CEQA. Is that right? Or does the ballot language say a court must decide the appeal within 270 days?

Any challenge to an eligible water supply project is to be resolved (e.g., decided by a court) within 270 days after the certified administrative record is filed with the court. This is substantially similar to previously adopted legislation including AB 900 and subsequent acts based on AB 900 (which expedited treatment of various projects—See CA Office of Planning and Research Website), and various other statues providing for litigation streamlining (see also SB & Atkins – Jobs and Economic Improvement Through Environmental Leadership Act of 2021 -adopted this year).

If you’ve waded through the preceding series of questions and answers, at the least you may understand that in no way was our intent to gut the protections embodied in CEQA or the Coastal Act. Rather our goal was to streamline the process, so project proposals would get a yes or no answer within years instead of decades. One would think that is a reasonable expectation.

Moreover, nothing in our initiative affected the many strong Federal regulations designed to ensure that infrastructure projects don’t harm the environment. Nor did we curb the ability for the California Dept. of Fish and Wildlife to scrutinize, and as they all too often do, derail any project. Finally, as cannot be emphasized enough, we left final decisions as to which projects would receive funding pursuant to our initiative up to the California Water Commission. To say that body has been adequately attentive to the concerns of the environmental community in California would be a gross understatement.

None of this mattered. We offered a solution that replaced scarcity with abundance, insecurity with security, punitive rationing and intrusive demand management with practical water supply infrastructure. In short, we offered a pathway out of the gloom and doom narrative that is the currency of environmentalists in the world today. And that was unforgiveable.

This article originally appeared on the website of the California Globe.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.