“We cannot support your initiative if you include the Delta Tunnel as an eligible project. And to be clear, we also cannot support your initiative if you do not include the Delta Tunnel as an eligible project.”

This statement, which I heard with my own ears sometime in early September 2021, was made by someone painfully aware of the paradox it expressed. It epitomizes how California’s farmers confront the existential threat of not enough water to irrigate their crops. They are bitterly divided over what solutions to support. If your farm is located north of the California Delta, you don’t want Southern Californians to build a giant straw that will suck the Northern Central Valley dry. And if your farm is south of the Delta, escalating restrictions on pumping water into southbound aqueducts from fragile Delta ecosystems makes a tunnel an elegant solution.

Disagreement over how to transport water through, around, or under the Delta is just one of many causes of gridlock in California over water policy, but the scale of the project and the effect it would have make it central to discussions over state water priorities. Taking an unequivocal stand on the Delta Tunnel—for or against—will immediately either alienate or attract about half of California’s farming community, along with every water agency, urban or rural, northern or southern, that is affected by it.

Not only are farmers in the Sacramento Valley to the north generally set against constructing the tunnel, while farmers in the San Joaquin Valley to the south generally support construction. There are also the farmers

within the Delta, a vast area of reclaimed land, much of it lying slightly

below sea level and protected by

over a thousand miles of levees. These farmers, for the most part, oppose the Delta Tunnel because a tunnel will divert water north of the Delta, possibly leading to less available water to irrigate their fields. In this they share the concerns of Sacramento Valley farmers, but they also have an equally urgent concern regarding levee maintenance.

As it is, the Southern California water districts that receive water thanks to the Delta pumps are paying much of the cost to maintain the Delta levees. Once a tunnel bypasses the Delta, the incentive for powerful Southern California water districts to provide financial and political support for Delta levees, and by extension, Delta farming, will disappear. And if that happens, the Delta farmers will lose the allies they need to maintain their levees and resist pressure from environmentalists to systematically eliminate the levees and the reclaimed agricultural land in favor of turning the entire Delta back into a nature preserve.

These conjectures serve just to offer a glimpse into the complexity of the issues affecting whether or not to construct a Delta tunnel. The gridlock over the tunnels has a negative impact on many other projects. For example, if the Delta tunnel is built, the Sites Reservoir—a proposed off-stream reservoir that would capture storm runoff in a valley west of the Sacramento River and north of the Delta—would be able to release its water to customers south of the Delta with none of the pumping constraints currently in place. Without the Delta tunnels, runoff pumped into the Sites Reservoir would be more likely to be reserved for use north of the Delta.

The Many Ways California’s Farmers Are Divided

The distinct and often conflicting interests between northern and southern farmers is further exemplified by the separate peace negotiated between environmentalists and California’s rice farmers, who are nearly all operating north of the Delta. The historical treatment of rice fields in the off-season was to burn the rice straw. From the perspective of modern sensibilities this was a rather unenlightened practice. Every year, smoke and soot from nearly 500,000 acres of burning fields would foul the air for hundreds of miles. But starting in the 1990s, in cooperation with environmentalists, California’s rice farmers began to flood their rice fields after the harvest instead of burning the straw, creating winter season wetlands. The practice spread, and by 2010 open field rice burning had been reduced by 90 percent. From October through February, the fallow fields become wetlands for migratory waterfowl.

This is a laudable accomplishment. Storm runoff is diverted, helping to prevent flooding. Aquifers are replenished as the sequestered water percolates. Rice straw decomposes and enriches the earth, instead of fouling the atmosphere. Migratory waterfowl along the legendary Pacific Flyway are given massive areas of new habitat. Along the Sacramento River, these flooded areas are now even being experimented with as potential habitat for salmon hatchlings.

This is a win-win, but it also may serve to further divide the farming community between north and south. Farming interests in the north, where the rice farmers are very influential, have less incentive to rock the boat. Environmentalists are powerful. They don’t want new water infrastructure and they believe farming at the current scale in California is not sustainable and must be reduced. Meanwhile, California’s rice farmers have made a deal with environmentalists, which could be in jeopardy if they support anything that environmentalists oppose. When they’re not coming after you, that is a rational business decision.

The problem with all of this becomes clear when you adopt a statewide perspective. And as we have seen, conservation is simply not enough to solve California’s challenge of water scarcity. There are solutions that can preserve farming in the San Joaquin Valley that ought to constitute reasonable compromises environmentalists can accept. But these solutions aren’t as obvious or as affordable as letting fallow rice fields accept winter floodwater in the water-rich north. A lot is at stake.

The Sacramento Valley, for all of its vast agricultural capacity, is only 40 percent as big as the San Joaquin Valley. North of the Delta in the Sacramento Valley there are 2.1 million acres of irrigated farmland. That’s a lot, but it is dwarfed by the San Joaquin Valley, where there are over five million acres of irrigated farmland. Finding a way to preserve this industry, which is the reason Californians consume affordable food and export food all over the nation and around the world, is something that ought to unite California’s farmers to work towards solutions for all of them, not just those north of the Delta.

Another geographic schism occurs within the San Joaquin Valley, where the impact of water allocations and regulations affect farmers on the west side much differently from farmers on the east side. This is evident when viewing a satellite image of the San Joaquin Valley. All of the farmers in the San Joaquin Valley are reliant to some extent on groundwater, to which access has also become problematic for them. And all of the farmers in the San Joaquin Valley also rely on northern water from the aqueducts. But the older, smaller farms on the eastern side of the valley are also able to tap surface runoff from the Sierras, which has been their historical source of water for farm irrigation. To the west, the much larger farms have no option but to rely almost exclusively on water from the California Aqueduct.

It isn’t just geography that divides California’s farmers. They are divided by what crops they grow, with rice only the most obvious example among many. In each case, the economics differ. Farmers growing crops that, for the same water input, have a high value, such as pistachios, can adapt to water restrictions that would put farmers specializing in row crops such as tomatoes out of business. On the other hand, farmers growing perennial crops in orchards and vineyards cannot skip a year of irrigation, or their trees and vines will die. Farmers planting annual row crops can choose which fields to leave fallow in a dry year.

Finally, farmers in California are divided by the scale of their operations. As regulations and restrictions have increased relentlessly over the past few decades, the size of the farming operation that can bear the overhead cost for compliance has grown proportionately. Wayne Western, Jr., who farms row crops in the San Joaquin Valley, said that a 10,000 acre farm used to be considered big, certainly big enough to apply economies of scale sufficient to adequately spread the cost of capital equipment and compliance overhead. Now a 10,000 acre farm is considered economically marginal. Many agribusiness holdings today are in excess of 100,000 acres, and consolidation is ongoing.

When it comes to which water policies and solutions to support, this division between big and small farmers is possibly the biggest source of disunity. The financial interests of large farms are not furthered by a thriving, diverse, and decentralized farm economy. To the extent very large agribusinesses supported, or considered supporting our initiative, it was not just an act of pure self interest. An environment of scarce and expensive water, and other inputs which have also seen sharp increases in price, are an opportunity for large farming corporations to buy out small farmers and increase their holdings. An operation with economies of scale and a strong balance sheet can withstand financial hardships that put the small farmers out of business. At the same time, as will be seen, scarce and expensive water makes speculation on land for its water rights an attractive proposition.

Failed Attempts to Increase Water Supply Infrastructure

If California’s farming community is divided over what to do about water, they are also frustrated by several recent attempts to increase their supply of water. All of them failed, or, in the case of Proposition 1 in 2014, are failures to-date. When Proposition 1 was approved by over two-thirds of California voters, the expectation was that the storage projects it specified would be funded and built. Not only have none of them been built so far, the Temperance Flat Dam proposal—which would have captured storm runoff on the San Joaquin River, above an already existing dam—was all but killed by the bureaucrats in Sacramento. How they performed this sleight of hand is illustrative of why many farmers feel betrayed by their own state government.

When the California Water Commission began to evaluate the projects approved by voters in Proposition 1 for funding, they came up with a scoring system whereby they awarded points based on “beneficial use.” But they defined beneficial use in a manner that overemphasized environmental benefits versus benefits to farm and urban water consumers. They then awarded funds to each voter-approved project based on the points each project earned. Temperance Flat, under these manipulated criteria, did not score very well, and the amount of money it was awarded was only a small fraction of what was needed.

By the time we began speaking with farmers about our water initiative, Proposition 1 in 2014 was just one recent example of how their efforts to affect water policy via an initiative had been thwarted. In 2018, proponent Jerry Meral had succeeded in putting Proposition 3 on the ballot. This expansive proposition, which Meral spent several years cobbling together in consultation with every interested party he could possibly identify, had something for everyone. In the $8.9 billion bond package, there was $855 million to repair aqueducts, $685 million to develop groundwater storage, and $472 million to develop and repair dams. The big bucks, $2.9 billion for “watershed and fisheries improvements,” and $3.0 billion for “safe drinking water and water quality,” may not have increased California’s water supply, but could be supported based on the improvements they would deliver to water quality in the state. Farmers supported Proposition 3 with donations and endorsements, joining a coalition that included every major environmental organization except for one—the Sierra Club. In a very tight race, Proposition 3 failed by only 155,000 votes out of nearly 12 million votes cast, a losing margin of only 1.3 percent.

There was yet another attempt to go to voters to fund water supply improvements in 2020, the “Dams Not Trains” initiative, led by proponent Aubrey Bettencourt. As its title indicates, this initiative would have redirected funds allocated for high speed rail to funding water storage infrastructure. This innovative bill also called for a redefinition of “beneficial use,” something we emulated in our initiative, and it took responsibility for approving water projects away from the California Water Commission, something we decided against. Once again, and for the third time in six years, many of California’s farmers stepped up with their donations and endorsements, but this time, the initiative failed to qualify for the ballot.

No wonder finding support from farmers proved to be problematic. They’ve been betrayed and they’ve been frustrated with initiative efforts three times in the past eight years, and many of them feel all that money was wasted. But the reality for most of them is only going to worsen. They face a hostile, do-nothing legislature, a hostile press, and an environmentalist movement that wants to eliminate most of them. California’s farmers will either successfully advocate for massive investment in new and upgraded water infrastructure, or, taking into account how many small farmers still operate in California, most of them will go out of business. But it isn’t as if, collectively, they don’t still have the resources for another fight.

Agribusiness in California directly employs over 800,000 people, with agricultural cash receipts estimated in 2020 at $49 billion. The indirect employment and GDP contribution as agricultural products are distributed and retailed, and as farm employees participate in the economy, multiplies those amounts. California’s farm industry may be fractured, but each of its constituent sectors have trade associations, with annual lobbying and political campaign budgets in the tens of millions and marketing budgets in the hundreds of millions.

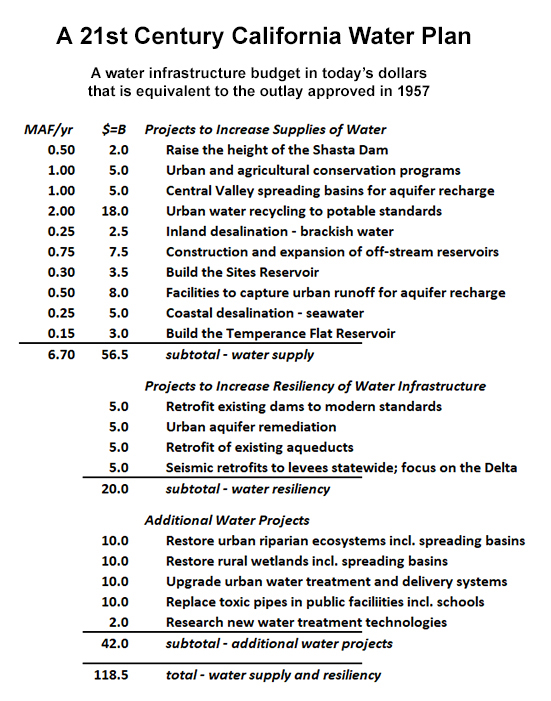

Without more water infrastructure in California, i.e., without a comprehensive statewide plan to spend $50 billion or more, right away, on an all-of-the above program of water investments ranging from new reservoirs and reservoir upgrades to recycling all urban wastewater, the future for most of California’s farmers is grim. California agribusiness needs to think big, identify what it is they agree on while taking into account the needs of the entire state, pool their resources, form stronger alliances with urban water agencies and others; they need to identify, expose and resist environmental extremism, and they need to unite and fight for the changes necessary for all of them to survive and thrive.

This article originally appeared on the website of the California Globe.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.