How Many Laws Does San Francisco’s Prop. A Violate?

Whether or not San Francisco’s upcoming appeal to voters to borrow $600 million to pay for for low income housing is a good idea or a bad idea depends on who you ask.

Proponents claim Prop. A, which will appear on the ballot this November 5th, is necessary because San Francisco doesn’t have enough affordable housing. Opponents argue, among other things, that Prop. A is mostly for “rehabilitation” of existing low income housing and therefore doesn’t significantly increase the supply of housing.

But does Prop. A’s proposed use of funds conform to state law that directs how bond money can be spent?

Does Prop. A’s Use of Proceeds Violate California’s State Prop. 46?

Eight years after the passage of the landmark Prop. 13, which California’s voters approved in 1978 to freeze property taxes at one percent of the assessed value at that time (with a maximum two percent per year permissible adjustment), Prop. 46 was passed by voters to offer some exemptions to Prop. 13. Specifically, Prop. 46 authorized local governments to increase property taxes if, by a two-thirds vote, ballot measures were approved to permit borrowing “to purchase or improve land and buildings.”

Prop. A’s proposed use of funds appears to skate very close to the edge in terms of complying with Prop. 46, because there is a difference between “improvement” and “repairs.” In the world of accounting and finance, this difference is significant. The distinction between capital improvements and repair expenses is clearly defined in generally accepted accounting principles which govern how they are classified on certified financial statements as well as on tax returns.

The underlying ordinance to be approved via Prop. 8 reads as follows: “to finance the construction, development, acquisition, improvement, rehabilitation, preservation, and repair of affordable housing…”

An improvement would be to add square footage to a building, or to add a significant amenity such as a swimming pool, that had not previously been on the property. Those expenditures conform to Prop. 46’s restrictions, because they are capital improvements. It is difficult, however, to discern how “rehabilitation, preservation, and repair” complies with Prop. 46, because those are not capital improvements, they are repair expenses.

If you review the spending budget for Prop. A via the text of the ordinance, in Section 3 “Proposed Program,” it becomes even more difficult to argue these expenditures are going to be for “improvement” as opposed to “repair.”

How Much of Prop. A’s Proposed Spending is Actually for “Acquisition and Improvements”?

First, let’s gallop through the “Proposed Program” as summarized in the text of the ordinance:

“Section A, Public Housing,” allocates $150 million to “repair and reconstruct distressed and dilapidated public housing developments.”

This $150 million is clearly not for capital improvements. It’s for maintenance.

Section B, “Low Income Housing,” allocates $220 million to “construct, acquire, and rehabilitate rental housing serving extremely-low and low-income individuals and families.”

Here it would be useful to know to what extent there is “acquisition and construction,” which presumably conforms to Prop. 46, and to what extent there is “rehabilitation,” which arguably does not.

Section C, “Preservation and Middle Income Housing” allocates $30 million to “acquire and/or rehabilitate existing housing at risk of losing affordability,” and “a minimum of $30 million to assist middle-income City residents or workers in obtaining affordable homeownership or rental opportunities.

The second portion of Section C is especially problematic. What does this even mean? It doesn’t appear to have anything to do with repair and rehabilitation of property, much less acquisition and improvement. Is it mortgage loans? Rent subsidies? How does this conform to Prop. 46?

Section D, “Senior Housing” allocates $150 million to acquire and construct new senior housing.

At face value this does conform to Prop. 46.

Section E, “Educator Housing” allocates $20 million to “support predevelopment and new construction of permanent affordable housing opportunities or projects serving SF Unified School District and City College of San Francisco educators and employees earning between 30% and 140% of AMI at the time the bonds are issued.”

Notwithstanding whatever “predevelopment” means, the “new construction of this” is not a violation of Prop. 46, but it constitutes a nice lottery jackpot for a very small handful of San Francisco’s public employees.

Section F states “a portion of the Bond shall be used to perform audits of the Bond.”

This is a good thing, but clearly not something authorized by Prop. 46.

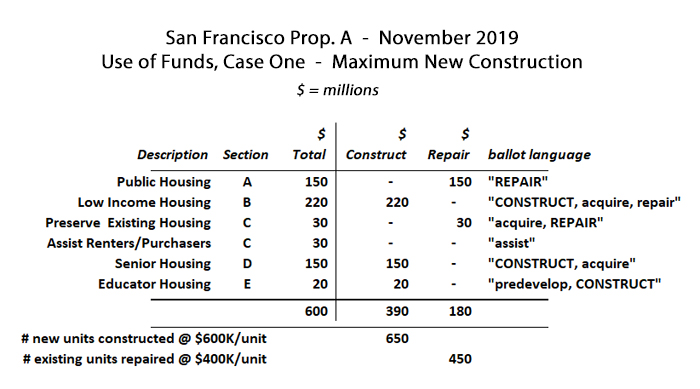

Based on this information, the following two tables provide estimates as to how much actual new housing will be created if Prop. A is passed. They rest on the reasonable assumption that new construction will cost an average of $600,000 per unit and rehabilitation of existing units will cost an average of $400,000 per unit.

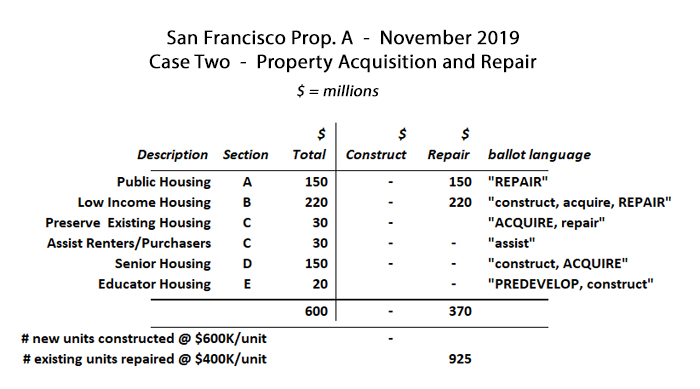

What are presented in these two cases are what might be considered a best case (#1) and a worst case (#2). The fact that these two cases present vastly differing estimates is because the language of the ordinance is deliberately vague. It doesn’t say “construct” new housing, or “rehabilitate” existing housing. Instead the language typically presents a choice, by wording it “construct or rehabilitate.”

As can be seen in Case One, below, based on the “Proposed Program” as described in the ordinance that Prop. A would approve, if 100 percent of the funds in every one of the six budget sections were allocated to construct new units if the language of the section permitted that, a total of 650 new units would be added to San Francisco’s housing stock.

That’s 650 new units of housing. For six hundred million dollars.

In Case Two, below, wherever the language in one of the six sections of the Proposed Program permits “repair,” “reconstruction,” or “rehabilitation” of existing units, that is where the funds are assumed to be spent. This is not a worst case scenario, in fact, because even in this case, Section B’s $220 million might be entirely used to acquire properties, leaving the job of repairing them to another future bond to fund. Instead, in this case the entire $220 million is assumed to be used for repair work on existing units.

As can be seen, under this second scenario, $600 million results in the rehabilitation of 925 units, with not one single new unit of housing being constructed. No Specificity Means No Accountability

No Specificity Means No Accountability

It is easy to question all the assumptions used in these two cases, but based on the performance of housing bonds in San Francisco and elsewhere in California over the past few years, the per unit cost assumptions to construct or to renovate are, if anything, too low. Why?

When so many people can’t afford housing, and the situation is so dire that supposedly public funding must come to the rescue, why is the City of San Francisco proposing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars per unit on buildings that are already occupied? Why are they acquiring properties, if these properties are already occupied? Why do housing projects have to be more lavish than the privately owned rental housing stock that the vast majority of renters live in and pay for without subsidies? Why does it cost so much to build or repair housing; what percent of total project costs are soft costs? Why not work on a regional basis, and build and repair housing in lower cost parts of the Bay Area?

More to the point, why is Prop. A worded in a manner that leaves the administrators of these funds leeway to do pretty much anything they want with the money? Why isn’t it specified, clearly, in each section, what percent of funds will be used for acquiring existing housing (if that’s even necessary), for constructing new housing units, or for repairing existing housing?

Even more to the point, why isn’t it specified, in each section, that for all funds being used to “rehabilitate” existing housing, one-hundred percent of these funds are being used to fund capital improvements, and not ordinary repairs? Could it be because that would violate the terms of Prop. 46, which only permits local property tax funded bonds for property purchases and capital improvements?

The proponents of San Francisco’s Prop. A are on thin ice, and there’s more.

Is the City of San Francisco Violating California Election Code?

No other major city in California, and probably no city anywhere in the state, permits paid arguments to be placed in a ballot pamphlet. But San Francisco does. Have a look at the ballot pamphlet, and note there are 22 “paid” arguments in favor of Prop. A, and two paid arguments opposing Prop. A.

The astute observer will also note the “three largest contributors to the true source [of funds for] the recipient committee” for fifteen of the paid arguments in favor of Prop. A is the same collection of contributors – “1. Chris Larsen, 2. Mercy Housing California, 3. Bridge Housing Corporation.” Who are these entities and what is their stake in the outcome of this vote?

That is a story in and of itself. Who benefits from the passage of Prop. 8? The paltry number of people who win the housing lottery and move into these subsidized units? Who else?

In any case, the disproportionate number of paid arguments supporting Prop. A isn’t the primary legal issue. The problem is that the maximum cost to place these paid arguments, which are political ads, is only $800. This is laughably less than what it actually costs the City of San Francisco to accept, process, print and distribute these political ads. To the extent the true cost to the city to distribute each of these ads exceeds the amount the proponents each paid for their ads, the city is subsidizing political advertising.

This possible violation of California election law may as well bode ill for attempts by the City of San Francisco to implement Prop. A, even if voters approve it. A small but determined group of activists and attorneys have already launched legal challenges to these and other questionable procedures and decisions by the city. How it plays out in the coming months should be interesting.

More pertinent than whether or not Prop. A adheres to the letter of the law in all its aspects, however, is the stupefying amount of money it proposes to spend for such a paltry gain. Six hundred million dollars for, at best, less than 1,000 units of new housing.

Increasing the supply of housing sufficiently to bring down the price for housing is a daunting challenge. But simple math demonstrates that Prop. A is not going to do anything to disrupt the current equilibrium. Should San Francisco’s voters approve it anyway? We will find out on Nov. 5th.

This article originally appeared on the website California Globe.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!