In a long-planned rally at the California State Capitol last month, San Joaquin Valley farmers protested new laws that impose taxes on their irrigation wells. In Madera County, where most of these farmers came from, the new tax is as high as $246 per acre of farmland. If you’re trying to irrigate a few sections of land to grow almonds, that tax adds up fast.

It would be bad enough for these farmers merely to restrict their access to groundwater, particularly since new laws are also restricting their access to river water. But the timing of this tax couldn’t be worse. The cost for diesel fuel has doubled, fertilizer cost has tripled, and shipping bottlenecks prevented farmers from selling their produce to export markets, flooding the domestic market and driving the price down.

Less revenue. Higher costs. And now a per acre tax on wells. Speaking at the farmer protest, state Sen. Melissa Hurtado exposed the hidden agenda behind the ill-timed regulatory war on farmers. “Financial speculators are buying farmland for the water rights,” she said, “and then they turn around and sell your water right back to you.”

Hurtado is right. The immutable algebra of this predatory financial strategy goes like this: As regulatory oppression drives farmers out of business, investors move in and buy their land. Meanwhile, these investors support environmentalist restrictions on river withdrawals for irrigation and oppose water supply infrastructure projects (using environmentalist justifications), in order to create a shortage of available water. Next, they use water rights to sell water back to corporate farmers who move onto the acquired properties, as well as to other farmers and municipal customers. Then they blame the inflated prices on “climate change.”

The accelerating movement of speculative investment capital into American farmland is well documented. According to the USDA, foreign investors by 2019 had purchased over 35 million acres of U.S. farmland. To put this in perspective, there are nearly 900,000 square miles of agricultural land in the U.S. (the entire lower 48 is 1.9 billion acres), but the impact of these purchases aren’t evenly distributed. Foreign investors favor prime irrigated farmland, of which there are only about 58 million acres in the U.S. Ground zero for this is California, with 9.6 million acres of irrigated farmland.

Because of California’s politically contrived water scarcity, farmland investment gravitates to California and is motivated as much by the desire to secure the lucrative water rights as it is to grow food. And while foreign investors are part of the mix, most of the purchases are being made by American firms. For example, while Saudi investors are buying land for the water rights in the Imperial Valley, Harvard’s $32 billion endowment is buying land for the water rights in Central California. American hedge funds and investment firms including Trinitas Partners, LGS Holdings Group, Greenstone, and others are also buying out California’s financially stressed farmers. Their profit model relies on water scarcity.

One of the primary sources of water for the American Southwest is the Colorado River. With decades of runoff stored in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, water is released downstream to sustain the cities of Phoenix, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and San Diego, along with countless smaller cities and large-scale agriculture, primarily in Arizona and California’s Imperial Valley. California alone imports more than four million acre feet per year from the Colorado River. And decades of reservoir overdrafts along with a prolonged drought are about to force a massive reduction in how much water can be taken from the Colorado.

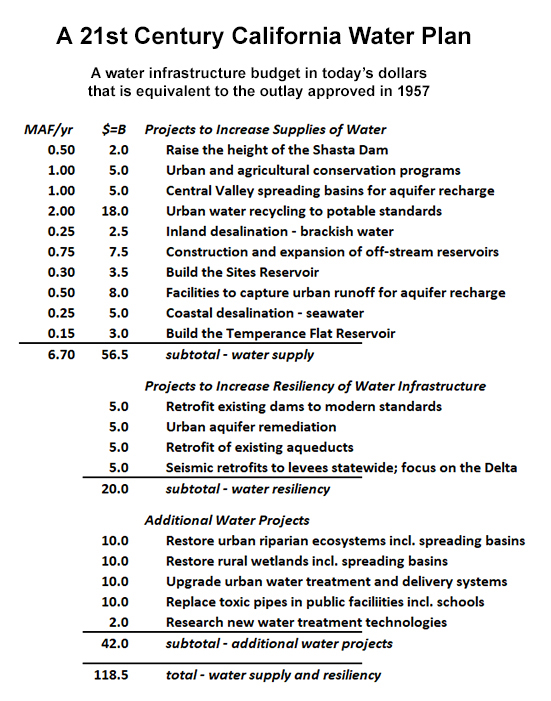

Public investment in water supply projects could have prevented the looming water crisis. Big new off-stream reservoirs such as the proposed Sites Reservoir in Northern California, could capture and store flooding runoff from the Sacramento River. Raising the height of the Shasta Dam, along with several other existing dams, could cost-effectively increase California’s water storage capacity. Spreading basins—and a return to flood irrigation—could also capture runoff along the entire western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and store millions of acre feet each year in underground aquifers. Urban water recycling could reduce the amount of water required by California’s cities by several million acre feet per year. Desalination plants can offer a perpetual, drought-proof supply of water to California’s coastal cities.

Instead, the only solution proposed by California’s policy makers is water rationing against a backdrop of chronic water scarcity and high prices. But it’s important to know what’s behind this, because the operative ideologies often have little to do with the classic liberal vs. conservative, capitalist vs socialist schisms. The powerful special interests who profit from water scarcity are speculative investors who use environmentalists to stop water supply projects. And while leftist environmentalists rhetorically attack capitalists, they have a symbiotic alliance with these investors. Both want water scarcity.

The irony, and the broken stereotypes, run deep. Consider the typical libertarian reaction to public investment in water supply infrastructure. “Let the market decide,” they will decree. But in many ways, the market is broken. Like many libertarian pieties, “the market” only works perfectly in a perfect world. In California, public funding of water supply projects results in a permanent lower cost for water and allows a water market to function against the backdrop of water abundance. This, in turn, enables a more decentralized ecosystem of competing farmers, selling more diverse agricultural products at lower prices, while still making a profit. At the same time, water abundance takes away the incentive for predatory investors to exploit water scarcity and turn the farming industry into the latest victim of what some call rentier capitalism.

State Sen. Hurtado, a Democrat whose district embraces the heart of the San Joaquin Valley, sees this clearly. So does embattled farmer John Duarte, running as a Republican to represent California’s 13th Congressional District. Duarte coined the term “Lords of Scarcity” to explain the phenomenon. A partisan assessment of these two politicians would place them squarely in the opposing camps of liberal and conservative. But they both recognize this phenomenon when they see it, and are equally committed to fighting its parasitic impact.

The organizers of the farmers’ protest also exemplify the new, stereotype-breaking coalition that is forming to oppose the financialization of agriculture. The leadership came from the Punjabi American Growers Group, nearly all of them family farmers who arrived in California within the last 50 years. What they found, until the Lords of Scarcity began the great squeeze, was a land where with hard work you could buy land and grow food and earn generational wealth. That way of life is threatened today, and these Punjabi Americans, along with millions of Americans of all backgrounds and ideologies, are waking up.

Solving water scarcity and preserving a diverse, decentralized, competitive, and profitable agricultural industry in California will require new coalitions, willing to expose the scarcity agenda that is shared by speculative investors and fanatic environmentalists. That new coalition is forming, and it can’t happen a moment too soon.

In a long-planned rally at the State Capitol last month, San Joaquin Valley farmers protested new laws that impose taxes on their irrigation wells. In Madera County, where most of these farmers came from, the new tax is $246 per acre of farmland. If you’re trying to irrigate a few sections of land to grow almonds, that tax adds up fast.

It would be bad enough for these farmers merely to restrict their access to groundwater, particularly since new laws are also restricting their access to river water. But the timing of this tax couldn’t be worse. The cost for diesel fuel has doubled, fertilizer cost has tripled, and shipping bottlenecks prevented farmers from selling their produce to export markets, flooding the domestic market and driving the price down.

Less revenue. Higher costs. And now a per acre tax on wells. Speaking at the farmer protest, State Senator Melissa Hurtado exposed the hidden agenda behind the ill-timed regulatory war on farmers. “Financial speculators are buying farmland for the water rights,” she said, “and then they turn around and sell your water right back to you.”

Hurtado is right. The immutable algebra of this predatory financial strategy goes like this: As regulatory oppression drives farmers out of business, move in and buy their land. Meanwhile, support environmentalist restrictions on river withdrawals for irrigation, and oppose water supply infrastructure projects (using environmentalist justifications), in order to create a shortage of available water. Use water rights to sell water back to corporate farmers who move onto the acquired properties, as well as to other farmers and municipal customers. Blame the inflated prices on “climate change.”

The accelerating movement of speculative investment capital into American farmland is well documented. According to the USAD, foreign investors by 2019 had purchased over 35 million acres of U.S. farmland. To put this in perspective, there are nearly 900,000 square miles of agricultural land in the U.S. (the entire lower 48 is 1.9 billion acres), but the impact of these purchases aren’t even. Foreign investors favor prime irrigated farmland, of which there are only about 58 million acres in the U.S. Ground zero for this is California, with 9.6 million acres of irrigated farmland.

Because of California’s politically contrived water scarcity, farmland investment gravitates to California, and is motivated as much by desire to secure the lucrative water rights as it is to grow food. And while foreign investors are part of the mix, most of the purchases are being made by American firms. For example, while Saudi investors are buying land for the water rights in the Imperial Valley, Harvard’s $32 billion endowment is buying land for the water rights in Central California. American hedge funds and investment firms including Trinitas Partners, LGS Holdings Group, Greenstone, and others are also buying out California’s financially stressed farmers. Their profit model relies on water scarcity.

One of the primary sources of water for the American Southwest is the Colorado River. With decades of runoff stored in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, water is released downstream to sustain the cities of Phoenix, Las Vegas, Los Angeles and San Diego, along with countless smaller cities and large scale agriculture, primarily in Arizona and California’s Imperial Valley. California alone imports more than four million acre feet per year from the Colorado River. And decades of reservoir overdrafts along with a prolonged drought are about to force a massive reduction in how much water can be taken from the Colorado.

Public investment in water supply projects could have prevented the looming water crisis. Big new off-stream reservoirs such as the proposed Sites Reservoir in Northern California, could capture and store flooding runoff from the Sacramento River. Raising the height of the Shasta Dam, along with several other existing dams, could cost-effectively increase California’s water storage capacity. Spreading basins – and a return to flood irrigation – could also capture runoff along the entire western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and store millions of acre feet each year in underground aquifers. Urban water recycling could reduce the amount of water required by California’s cities by several million acre feet per year. Desalination plants can offer a perpetual, drought proof supply of water to California’s coastal cities.

Instead, the only solution proposed by California’s policy makers is water rationing against a backdrop of chronic water scarcity and high prices. But it’s important to know what’s behind this, because the operative ideologies have little to do with the classic, outdated, liberal vs. conservative, capitalist vs socialist schisms. The powerful special interests who profit from water scarcity are speculative investors who use environmentalists to stop water supply projects. And while leftist environmentalists rhetorically attack capitalists, they have a symbiotic alliance with these investors. Both want water scarcity.

The irony, and the broken stereotypes, run deep. Consider the typical libertarian reaction to public investment in water supply infrastructure. “Let the market decide,” they will decree. But the market is broken. Like many libertarian pieties, “the market” only works perfectly in a perfect world. In California, public funding of water supply projects results in a permanent lower cost for water, and allows a water market to function against the backdrop of water abundance. This, in turn, enables a more decentralized ecosystem of competing farmers, selling more diverse agricultural products at lower prices, while still making a profit. At the same time, water abundance takes away the incentive for predatory investors to exploit water scarcity to turn the farming industry into the latest victim of rentier capitalism.

California State Senator Hurtado, a Democrat whose district embraces the heart of the San Joaquin Valley, sees this clearly. So does embattled farmer John Duarte, running as a Republican to represent California’s 13th Congressional District. Duarte coined the term “Lords of Scarcity” to explain the phenomenon. A partisan assessment of these two politicians would place them squarely in the opposing camps of liberal and conservative. But they both recognize rentier capitalism when they see it, and are equally committed to fighting its parasitic impact.

The organizers of the farmers protest also exemplify the new, stereotype breaking coalition that is forming to oppose the financialization of agriculture. The leadership came from the Punjabi American Growers Group, nearly all of them family farmers who arrived in California within the last 50 years. What they found, until the Lords of Scarcity began the great squeeze, was a land where with hard work you could buy land and grow food and earn generational wealth. That way of life is threatened today, and these Punjabi Americans, along with millions of Americans of all backgrounds and ideologies, are waking up.

Solving water scarcity and preserving a diverse, decentralized, competitive and profitable agricultural industry in California will require new coalitions, willing to expose the scarcity agenda that is shared by speculative investors and fanatic environmentalists. That new coalition is forming, and it can’t happen a moment too soon.

This article originally appeared in the Epoch Times.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.