Precautionary Principle Extremism

Most people with any understanding of risk are familiar with the precautionary principle. It is defined as “the precept that an action should not be taken if the consequences are uncertain and potentially dangerous.”

The precautionary principle is an important governing concept when applied to climate change mitigation. The possibility of human CO2 emissions causing a catastrophic climate outcome is used to justify major policy shifts designed to lower or even eliminate these emissions. The impracticality of this endeavor is considered insignificant in the face of potentially terrifying consequences of doing nothing.

A recent post on X by a prominent Englishman, Ben Goldsmith, offers an excellent example of this mentality at work. Goldsmith writes:

“Climate change ‘doubters’ share one thing in common: they lack any understanding of risk. There is a not-insubstantial risk that the world’s climate scientists (and pretty much the entire scientific community) are right, and we are now facing a civilisation-ending threat. Any reasonable risk management strategy would be to do whatever it takes to mitigate that risk. Ask one of these nutters this, if they knew that there was a 10% probability of a particular aircraft crashing on its next flight, would they board it? I doubt they would, even if the risk was 1%. And how about if all the engineers responsible for that aircraft said it was *going* to crash? These people are today’s equivalent to the appeasers of the 1930s, only stupider and far more dangerous. They must be discredited and defeated.”

There’s a lot to unpack here, as there is in Goldsmith’s sarcastic response to a critical reply accusing climate alarmists of being motivated by money and power. Goldsmith writes:

“The climate scientists are the ones making the money. Right. Not the giant global fossil fuel companies and their executives, paid lobbyists and shareholders.”

Apart from his social media remarks presenting a useful summary of “whatever it takes” alarmist thinking, something that deserves far more analysis and criticism than it gets, why Goldsmith? Why else highlight his opinions? Because Goldsmith, along with his alarmist certainty and propensity to verbally abuse his critics, was born into fabulous wealth, and his words exemplify the elitist arrogance that currently threatens the freedom of the world.

Goldsmith accuses giant global fossil fuel companies of still having a vested interest in climate denial, but ignores the fact that fossil fuel interests, all of them, have a vested interest in making sure supplies of the fuel they control never quite catch up to exploding global demand, because that increases their profits. A politically contrived, managed cutback of their production suddenly becomes climate virtue, instead of price fixing. And it’s fair to wonder if Goldsmith’s apparent preference for non-fossil fuel solutions has anything to do with his position as CEO of Menhaden Resource Efficiency PLC, an investment company that “seeks to generate long-term shareholder returns, by investing in businesses and opportunities, delivering or benefitting from the efficient use of energy and resources.” Would that include any “renewables?”

When you’ve lived in an environment of fabulous wealth, it’s easy to sit back and call people who question your precautionary principle extremism “nutters, “stupid,” “dangerous,” and “freaks.” But as someone invested in “energy and resources,” Goldsmith is certainly aware of the BP Statistical Review of Global Energy, one of the most authoritative sources available on what fuels power the world. And with only a rudimentary aptitude for basic arithmetic, Goldsmith must know that for everyone on earth to consume only half the energy that Americans consume, per capita, global energy production will have to double. And, also reported in BP’s annual digest, “renewables” only provided 6.7 percent of total energy consumed worldwide in 2021, the most recent year for which we have data.

Goldsmith also is savvy enough to know that abundant, affordable energy is a prerequisite for prosperity, and that without it, upward mobility for low income communities in the developed world, along with entire nations in the developing world, is impossible. Goldsmith knows that barring unforeseen breakthroughs in energy technologies, achieving “net zero” by 2050 is impossible. But nonetheless, he claims we must all do “whatever it takes to mitigate that risk,” the risk, that is, of a climate catastrophe. But how much risk are we really talking about?

A few years ago, Ph.D geophysicist Judith Curry, current chair of the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, published a report on sea level rise in which she evaluated the most recent IPCC analysis along with several other international and national assessment reports. Her conclusions, which she maintains are consistent with the evidence, include this: “In many of the most vulnerable coastal locations, the dominant causes of local sea level rise are natural oceanic and geologic processes and land use practices. Land use and engineering in the major coastal cities have brought on many of the worst problems, notably landfilling in coastal wetland areas and groundwater extraction.”

She follows up to conclude that “the appropriate range of sea level rise scenarios to consider for 2100 is 0.2–1.6 m. Values exceeding 2 feet are increasingly weakly justified. Values exceeding 1.6 m require a cascade of extremely unlikely to impossible events, the joint likelihood of which is arguably impossible.”

Arguably impossible. Does an event that is “arguably impossible” justify “any means necessary” to avoid it? What about the other possible consequences of this alleged climate crisis we face? The following series of graphs present data that contradicts the climate panic narrative. They are just a small sampling of what is known and available. In virtually every type of climate trend, the data does not back up the nonstop alarm.

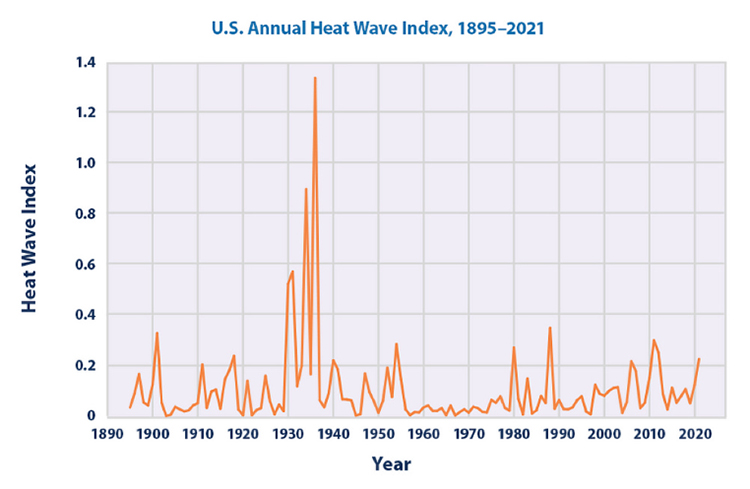

To begin with, “global warming,” which has morphed into “climate change,” along with the more recent “global boiling,” is itself questionable. Using data from the U.S. EPA’s “Climate Change Indicators in the United States,” the prolific fossil fuel champion Alex Epstein has produced a chart that clearly shows far more alarming incidences of heat waves in the 1930s. Imagine what ABC’s eminent thespian masquerading as a journalist, nightly news anchor David Muir, would have said about the 1930s dust bowl. Most climate scientists agree there is a gradual worldwide warming trend that began around 1850 when earth emerged from the so-called Little Ice Age. But there is ample data indicating warming in recent decades is not accelerating or unprecedented. Yet the hype is unceasing.

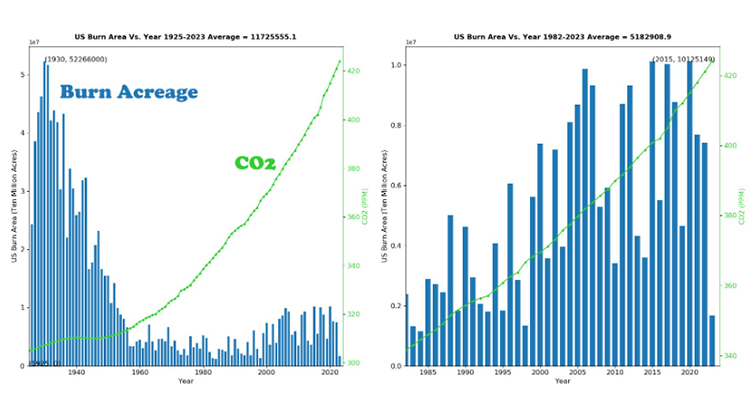

For wildfires, the graph on the right shows what alarmists depict as a terrifying trend. But the graph on the left widens the timescale to put recent years into perspective. Yes, acres burned has risen since the 1980s. But if you go back to the 1930s, it is clear that the extent of fires today is a mere fraction of what burned nearly a century ago. This graph was posted on X by Tony Heller, and it corroborates with data from the US Dept of Agriculture, National Report on Sustainable Forests – 2010, pg II-48. By any reasonable historical standard, America’s forests are not burning up.

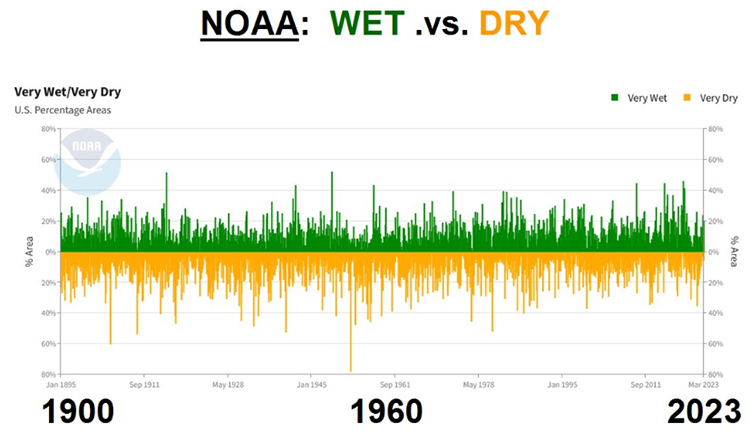

This next chart, posted on X by John Shewchuk, and originally posted by the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, shows over a century of data indicating the percent of area in the U.S. that was either “very wet” or “very dry.” It is clear from this chart that if anything, precipitation is generally increasing in the U.S., and since water is life, that is a very good thing. America has not entered an era of excessive droughts.

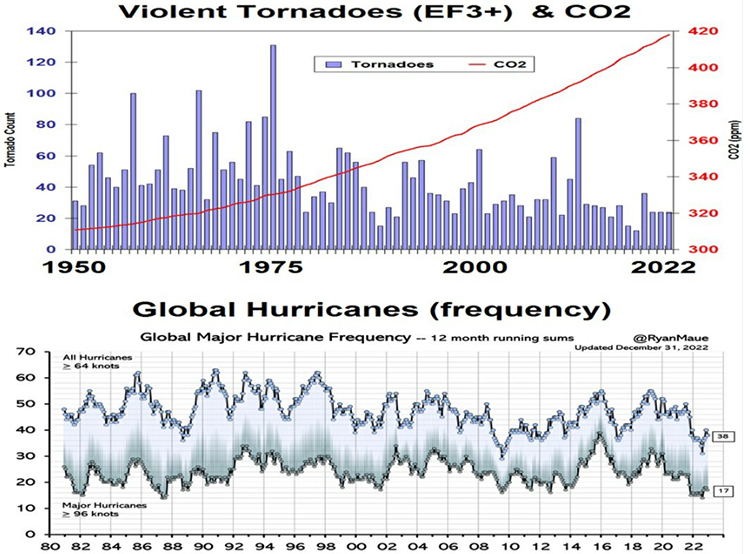

What about tornados? For this, again using data from NOAA, the incidence of strong to violent tornadoes in the US has trended down over the past 70 years. Global “major hurricane” frequency is also flat if not slightly down. The next graphic depicts both of these trends. America is not experiencing an epidemic of tornadoes, and the world is not experiencing an epidemic of major hurricanes.

This rendering was created by John Shewchuck, but its origins are traced to compilations by Wei Zhang, using data from NOAA, the National Weather Service, and reputable studies. Wei, a climate scientist at Princeton University and research scientist with NOAA, has the following quotes pinned to the top of his profile on X:

“I call it the “climate industrial complex”. So many people now make a living off of the #ClimateCrisis that there is no way they will let the narrative die, regardless of what the data shows.”

On August 29, Wei noted that “Censorship is everywhere now. I’ve made perhaps three edits in my life to Wikipedia. I don’t remember doing anything on climate. I think I edited LPGA golf page once. But somehow, I’m on Wikipedia master censorship list for my dangerous views.”

Which brings us back to Ben Goldsmith, who in another comment he recently posted on X said that “Quite a few nutters on here claiming there is in fact *zero* risk of the scientific community being right on the climate threat. Zero, they say, with tremendous confidence. Climate doubter Twitter is a whole new level of stupid.”

Goldsmith’s annoyance over links and observations on X belatedly allowing us to find scientifically valid evidence that most scientists and government institutions don’t themselves acknowledge is because it refutes the entire climate alarm paradigm. When examining the evidence, instead of biased models, all we are left with is a remote chance that catastrophic climate change is imminent, and if so, an even more remote possibility we can actually do something about it. And on that dubious basis, instead of adapting and thriving, we are told to dismantle our civilization, consigning ourselves to poverty and tyranny.

This is an extremist application of the precautionary principle, and it violates any genuine understanding of risk, for the simple reason it exchanges one very likely catastrophe – an energy starved civilization descending into mass poverty, oppression and war – for one very unlikely catastrophe, a global climate meltdown so severe it defies any attempts by humans to adapt.

Perhaps, Mr. Goldsmith, you are the one who lacks any understanding of risk.

This article originally appeared in American Greatness.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!