Nobody knew how the fire started. It took hold in the dry chaparral and grasslands and quickly spread up the sides of the canyon. Propelled by winds gusting over 40 miles per hour and extremely dry air (humidity below 25 percent), the fire spread over the ridge and into the town below. Overwhelmed firefighters could not contain the blaze as it swept through the streets, immolating homes by the hundreds. Even brick homes with slate roofs were not spared. Before it finally was brought under control, 640 structures including 584 homes had been reduced to ashes. Over 4,000 people were left homeless.

Does this sound like the “new normal?” Maybe so, but this description is of the Berkeley fire of 1923. In its time, with barely 4 million people living in California, the Berkeley fire was a catastrophe on par with the fires we see today.

When evaluating what has happened nearly a century since the Berkeley fire, two stories emerge. The story coming from California’s politicians emphasizes climate change. The other story, which comes from professional foresters, stresses how different forest management practices might have made many of the recent fires far less severe—and perhaps avoided entirely.

Specifically, California’s misguided forest management practices included several decades of successful fire suppression, combined with a failure to remove all the undergrowth that results when natural fires aren’t allowed to burn.

Back in 1923, tactics to suppress forest fires were in their infancy. But techniques and technologies improved apace with firefighting budgets. By the second half of the 20th century, an army of firefighters could cope very effectively with California’s wildfires. The result is excessive undergrowth, which not only creates fuel for catastrophic and unmanageable superfires, but competes with mature trees for the sunlight, water, and soil nutrients needed for healthy growth.

This is the real reason why California’s forests are not only tinderboxes but are also filled with dying trees. Now Californians confront nearly 20 million acres of overgrown forests.

By the time you read this, Californians may be coping with yet another round of superfires. During the 2020 fire season, an estimated 4.2 million acres burned, the most since recordkeeping began. To put this into perspective, this is more than 6,500 square miles, an area nearly the size of the State of New Jersey.

To gauge the extent of the devastation, relying on the square miles of the containment areas may be somewhat misleading. Drive up Highway 70 in the Feather River Canyon today and note that while all of it was designated as burned, the destruction was uneven, with some hillsides left intact while others were scorched.

But there is no question that some of the most devastating fires in modern history have hit California in recent years, killing hundreds, displacing thousands, and costing billions.

Clearly, when the state faces multi-year droughts, the summer fire risk gets progressively worse. In such conditions, a few lightning strikes can spark a conflagration. But during the 2020 fire season, why is it that the Creek Fire consumed nearly 400,000 acres and displaced over 12,000 people, but spared the forests surrounding Shaver Lake? What happened?

It wasn’t luck. The forests around Shaver Lake had been carefully managed for decades. The undergrowth was regularly thinned, either mechanically or through controlled burns, and mature trees were selectively logged. These practices nurtured an ecosystem that was, and remains, healthier and more diverse than those found even in forests that remain untouched by fires. Why aren’t all of California’s forests managed the way Shaver Lake is managed?

Negligence, not Climate Change, Causes Superfires

In 2019, President Trump tweeted, “The Governor of California, @GavinNewsom, has done a terrible job of forest management.” Newsom tweeted back, “You don’t believe in climate change. You are excused from this conversation.”

Meanwhile, former California Governor Jerry Brown addressed Congress in October 2019, saying, “California’s burning while the deniers make a joke out of the standards that protect us all. The blood is on your soul here and I hope you wake up, because this is not politics, this is life, this is morality. You’ve got to get with it—or get out of the way.”

Despite California’s current and former governors both being ardent members of the catastrophe chorus, climate change is not the primary cause of California’s recent superfires. Newsom, Brown, other extreme environmentalists, and the policies they demanded, are the reason California’s wildlands are going up in flames. They are the ones who need to be excused from the conversation. They are the ones who need to get out of the way. They are the ones who are in denial.

For about 20 million years, California’s forests endured countless droughts, some lasting over a century. Natural fires, started by lightning and very frequent in the Sierras, were essential to keep forest ecosystems healthy. In Yosemite, for example, meadows used to cover most of the valley floor, because while forests constantly encroached, fires would periodically wipe them out, allowing the meadows to return. Across millennia, fire-driven successions of this sort played out in cycles throughout California’s ecosystems.

Also for the last 20 million years or so, climate change has been the norm. To put this century’s warming into some sort of context, Giant Sequoias once grew on the shores of Mono Lake. For at least the past few centuries, forest ecosystems have been marching into higher latitudes because of gradual warming. In the Sierra Foothills, oaks have invaded pine habitat, and pine, in-turn, have invaded the higher elevation stands of fir. Today, it is mismanagement, not climate change, that is the primary threat to California’s forests.

This can be corrected.

In a speech before Congress in September, Representative Tom McClintock (R-Calif.) summarized the series of policy mistakes that are destroying California’s forests. McClintock’s sprawling 4th congressional district covers 12,800 square miles, and encompasses most of the Northern Sierra Nevada mountain range. His constituency bears the brunt of the misguided green tyranny emanating from Washington, D.C. and Sacramento.

“Excess timber comes out of the forest in only two ways,” McClintock said. “It is either carried out or it burns out. For most of the 20th Century, we carried it out. It’s called ‘logging.’ Every year, U.S. Forest Service foresters would mark off excess timber and then we auctioned it off to lumber companies who paid us to remove it, funding both local communities and the forest service. We auctioned grazing contracts on our grasslands. The result: healthy forests, fewer fires and a thriving economy. But beginning in the 1970s, we began imposing environmental laws that have made the management of our lands all but impossible. Draconian restrictions on logging, grazing, prescribed burns and herbicide use on public lands have made modern land management endlessly time-consuming and ultimately cost-prohibitive. A single tree thinning plan typically takes four years and more than 800 pages of analysis. The costs of this process exceed the value of timber—turning land maintenance from a revenue-generating activity to a revenue-consuming one.”

When it comes to carrying out timber, California used to do a pretty good job. In the 1950s the average timber harvest in California was around 6.0 billion board feet per year. The precipitous drop in harvest volume came in the 1990s. The industry started that decade taking out not quite 5 billion board feet, and by 2000 the annual harvest had dropped to just over 2 billion board feet. Today, only about 1.5 billion board feet per year come out of California’s forests as harvested timber.

Expand the Timber Industry

What McClintock describes as a working balance up until the 1990s needs to be restored. In order to achieve a sustainable balance between natural growth and timber removals, California’s timber industry needs to triple in size. If federal legislation were to guarantee a long-term right for timber companies to harvest trees on federal land, investment would follow.

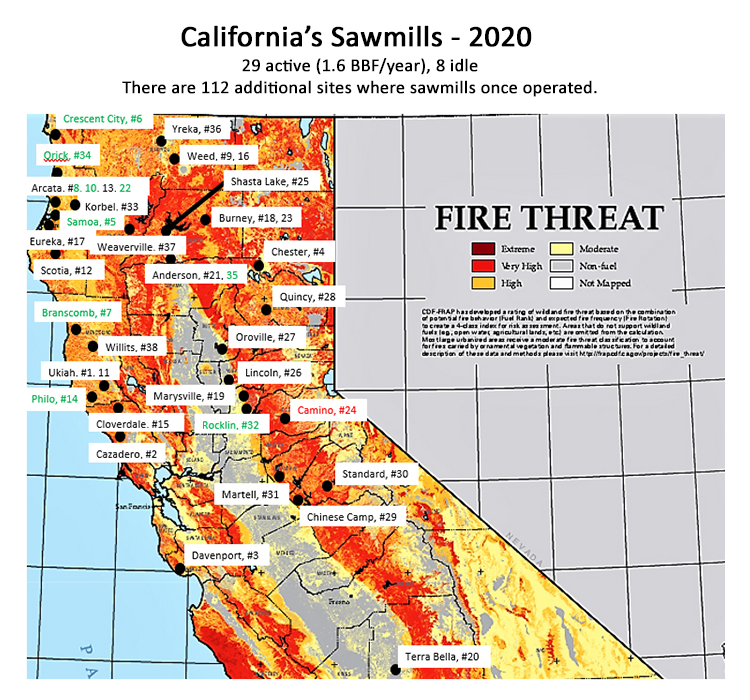

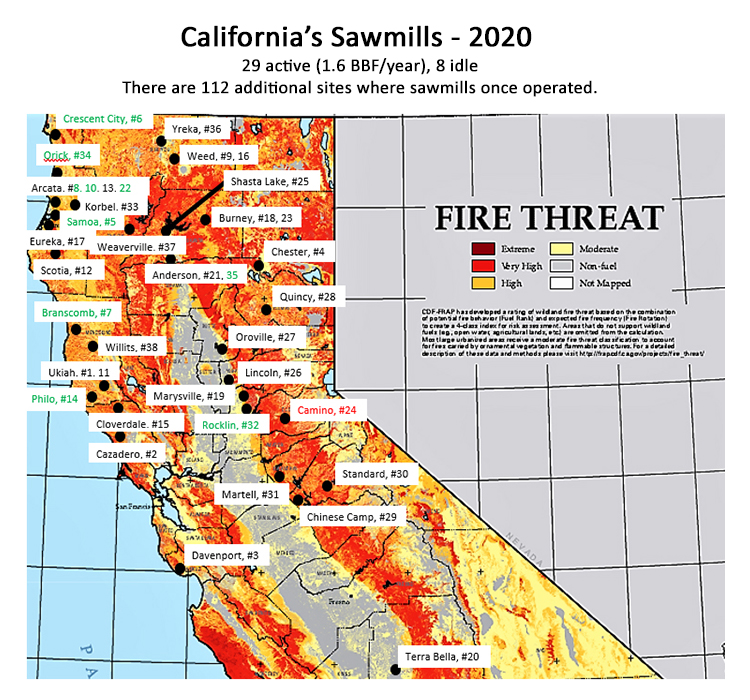

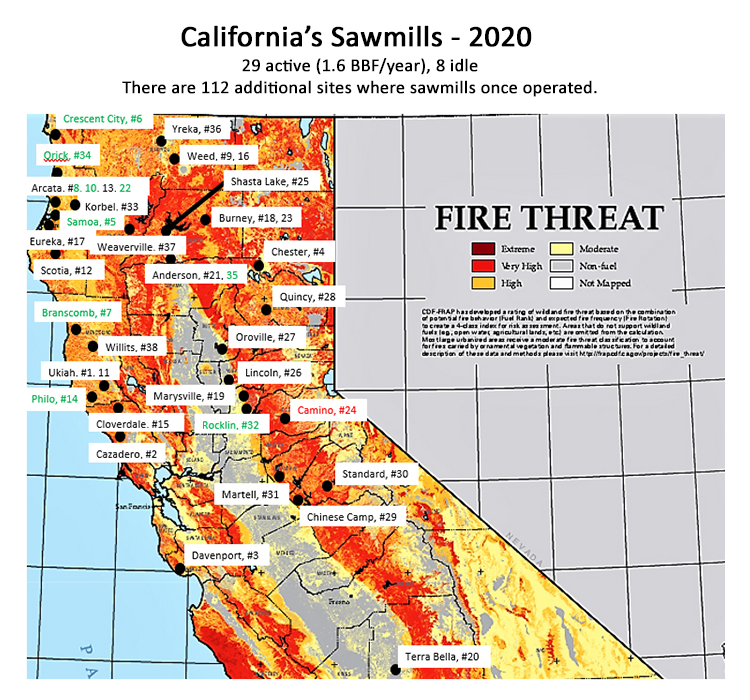

Today only 29 sawmills remain in California, along with eight sawmills that are still standing but inactive. In addition, there are 112 sites in California where sawmills once operated. In most cases, these vacant sites of former mills are located in ideal areas for rebuilding mills and resuming operations.

The economics of reviving California’s timber industry are compelling. A modern sawmill with a capacity of 100 million board feet per year requires an investment of $100 million. Operating at a profit, it would create 640 full-time jobs. Constructing 30 of these sawmills would create roughly 20,000 jobs in direct employment of loggers, haulers, and mill workers, along with thousands of additional jobs in the communities where they are located.

The ecological impact of logging again in California’s state and federal forests will not become the catastrophe that environmentalists and regulators once used as the pretext to all but destroy that industry. Especially now, with decades of accumulated experience, logging does more good than harm to forest ecosystems. There is ample evidence to prove it.

In forests managed by Sierra Pacific, for example, owl counts are higher than in California’s federally managed forests. Even clear-cutting, because it is done on a 60- to 100-year cycle, does more good than harm to the forests. By converting one or two percent of the forest back into meadow each year, areas are opened up where it is easier for owls to hunt prey. Also, during a clear cut, the needles and branches are stripped off the trees and left to rejuvenate the soil. The runoff is managed as well, via contour tilling which follows the topography of the hillsides. Rain percolates into the furrows, which is also where the replacement trees are planted.

How the Forests Surrounding Shaver Lake Were Saved

While clear-cutting will not destroy most ecosystems, since it is only performed on one to two percent of the land in any given year, there are other types of logging that can be used in areas deemed more ecologically sensitive. Southern California Edison owns 20,000 acres of forest around Shaver Lake in Southern California where they practice what is known as total ecosystem management.

Earlier this year, when the Creek Fire burned an almost unthinkable 550 square miles in Southern California, the 30 square mile island of SCE managed forest around Shaver Lake was unscathed. This is because for decades, SCE has been engaged in timber operations they define as “uneven age management, single-tree selection,” whereby the trees to be harvested are individually designated in advance, in what remains a profitable logging enterprise. Controlled burns are also an essential part of SCE’s total ecosystem management, but these burns are only safe when the areas to be burned are well-managed with logging and thinning.

The practice of uneven age management could be used in riparian canyons, or in areas where valuable stands of old-growth trees merit preservation. The alternative, a policy of hands-off preservation, has been disastrous. Tree density in the Sierra Nevada is currently around 300 per acre, whereas historically, a healthy forest would only have had around 60 trees per acre. Clearly, this number varies depending on forest type, altitude, and other factors, but overall, California’s forests, especially on federal lands, contain about five times the normal tree density. The result is trees that cannot compete for adequate moisture and nutrients, far less rain percolating into springs and aquifers, disease and infestation of the weakened trees, and fire.

This alternative—manage the forest or suffer fires that destroy the forest entirely—cannot be emphasized enough. In the Feather River Canyon, along with many other canyons along the Sierra Nevada, the east-west topography turned them into wind tunnels that drove fires rapidly up and down the watershed. Yet these riparian areas have been among the most fiercely defended against any logging, which made those fires all the worse. The choice going forward should not be difficult. Logging and forest thinning cannot possibly harm a watershed as much as parched forests burning down to the soil, wiping out everything.

Expand the Biomass Power Industry

If removing trees with timber operations is essential to return California’s forests to a sustainable, lower density of trees per acre, mechanical removal of shrub and undergrowth is an essential corollary, especially in areas that are not clear cut. Fortunately, California has already developed the infrastructure to do this. In fact, California’s biomass industry used to be bigger than it is today, and can be quickly expanded.

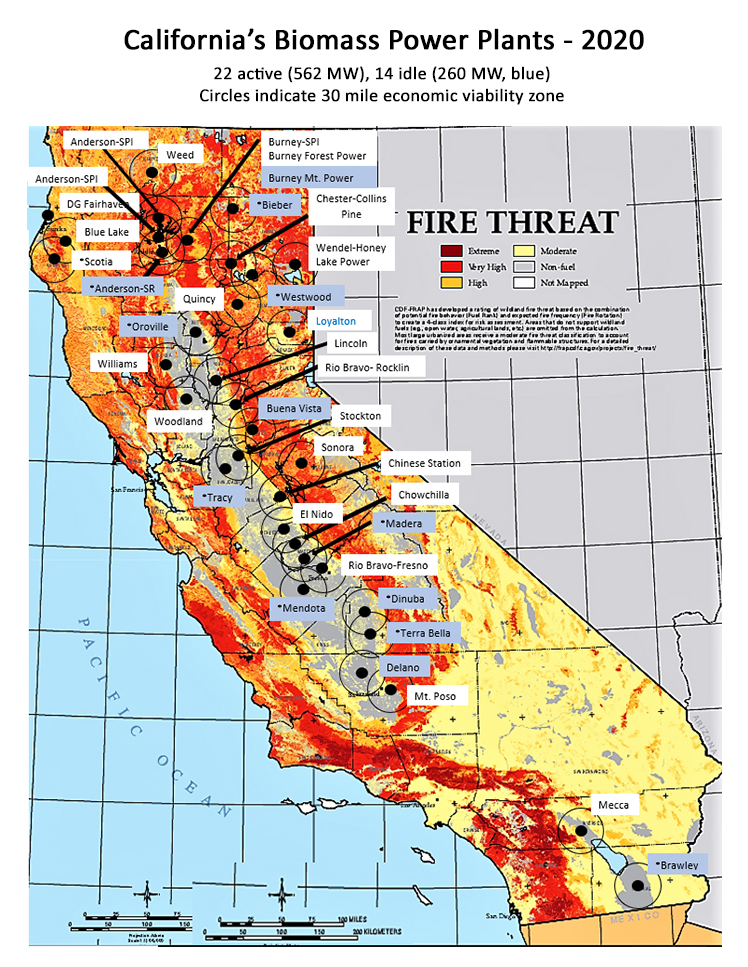

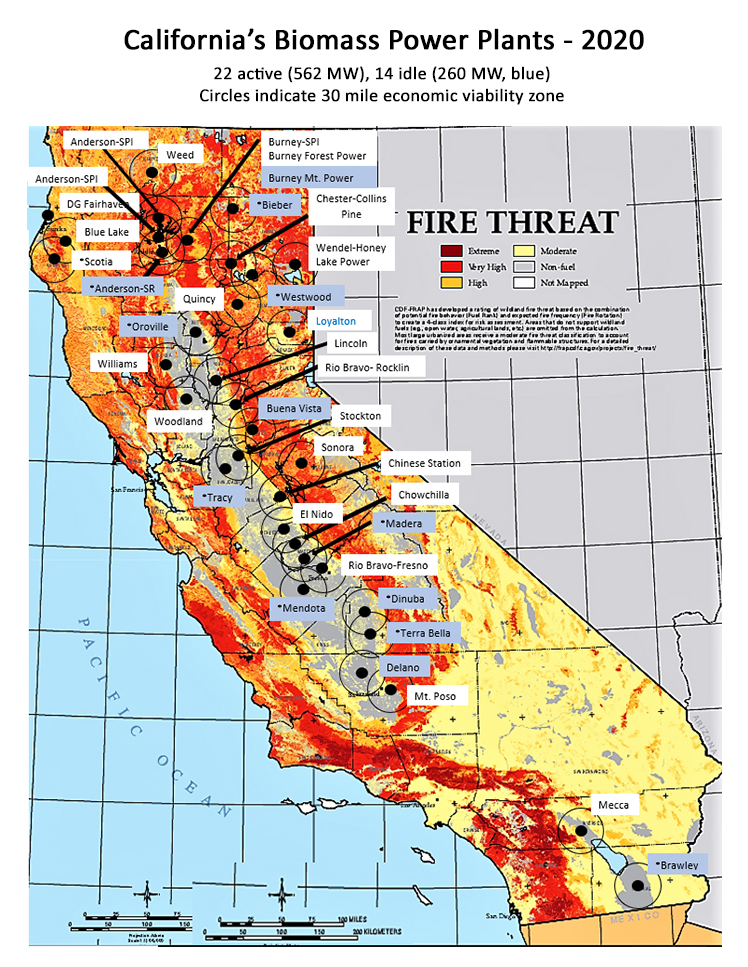

Today there are 22 active biomass power plants in California, generating just over a half-gigawatt of continuous electric power. That’s one percent of California’s electricity draw at peak demand; not a lot, but enough to matter. Mostly built in the 1980s and ’90s, at peak, there were 60 biomass power plants in California, but with the advent of cheaper natural gas and cheaper solar power, most of them were shut down. These clean-burning plants should be reopened to use forest trimmings, as well as agricultural waste and urban waste as fuel.

At a fully amortized wholesale cost estimated somewhere between 12 cents and 14 cents per kilowatt-hour, biomass power plants cannot compete with most other forms of energy. But this price is not so far out of reach that it could not be subsidized using funds currently allocated to other forms of renewables, infrastructure, or climate change mitigation. Moreover, this kilowatt-hour price necessarily includes the labor-intensive task of going into the forests and extracting the biomass, creating thousands of good-paying jobs. The numbers could work.

If, for example, biomass power capacity in California were roughly doubled to one gigawatt of continuous output, a six cents per kilowatt-hour subsidy would cost about $500 million per year. This must be compared to the annual cost of wildfires in California, which easily exceeds a billion per year. It also must be compared to the amount of money being thrown around on projects far less urgent than rescuing California’s forest ecosystems, such as the California High Speed Rail project, which has already consumed billions. And if this entire subsidy of $500 million per year were spread into the utility bills of all Californians, it would only amount to about a 1.5 percent increase.

Further in support of this economic analysis is the fact that much of the kilowatt-hour price for biomass electricity is amortization of the initial construction cost of the generating plant. If, as appears likely, Americans endure another multi-year bout with broad-based inflation, that fixed amortization cost will become less significant as all electricity rates rise with inflation. That, in turn, would make biomass electricity more competitive, reducing the required subsidy.

Pressure the Feds

About half of California’s forests lie on federal land. Does that mean nothing can be done? Far from it. With Democrats from California presiding over the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives, and a sitting president who owes his position to California-based tech billionaires and tech corporations, whatever California really wants from the federal government, California is going to get.

Here’s what they should be asking for:

Revise the EPA’s “no action” restrictions, usually based on the “single-species management” practice, have led to more than half of California’s national forests being off-limits to tree thinning, brush removal, or any other sort of active management.

Change the U.S. Forest Service guidelines which only permit active forest management, even in the areas that are not off-limits, for as little as six weeks per year. While restrictions on when and where forests can be thinned may have sound ecological justifications in some ways, they are making it impossible to thin the forests. The ecological cost/benefits need to be reassessed. To be effective, thinning operations need to be allowed to run for several months each year, instead of several weeks each year.

The EPA needs to streamline the NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) application process so it is less expensive and time-consuming for qualified companies to get permits to extract timber from federal lands. They can also grant waivers to allow thinning projects to bypass NEPA, or at the least, broaden the allowable exemptions.

The federal government can accelerate granting of long-term stewardship contracts whereby qualified companies acquire a minimum 20-year right to extract wood products from federal lands. This would guarantee a steady supply of wood products which, in turn, would make new investment viable in logging equipment, mills, and biomass energy facilities.

Rules and conditions governing timber exports need revision. The export of raw logs from federal lands in the Western United States is currently prohibited. Lifting this prohibition would help because sawmill capacity is not capable of handling the increase in volume. Just with the new thinning programs already in place, logs and undergrowth are being burned or put in landfills.

As it is, California imports around 80 percent of the cut lumber used in its construction industry or sold through retailers to consumers. If there was an assurance of wood supply—which the national forests can certainly offer—investment would be made in expanding mill capacity. Suddenly the money that is being sent to Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia to purchase their cut timber would stay here in California, employing thousands of workers in the mills.

The state or federal government can set up revolving loan funds for investors to build sawmills, as well as biomass energy facilities, as well as chippers and other equipment, that would allow the industry to quickly ramp up operations and capacity.

Will Politicians Do the Right Thing?

The logic of these steps seems impeccable. Thin the forests. Restore them to ecological health. Adopt time-tested modern logging practices and revive the timber industry. Build biomass power plants on the perimeter of the forests. Reissue grazing permits for additional cost-effective brush thinning. Prevent ridiculous, costly, horrific, tragic wildfires. Help the economy.

But these steps have been known for decades, and nothing has been done. Every time policymakers were close to a consensus on forest thinning, government bureaucrats obstructed the process and the environmentalists sued to stop the process. And they won. Time and time again. And now we have this: millions of acres of scorched earth, air so foul that people couldn’t leave their homes for weeks, and wildlife habitat that in some cases may never recover.

California’s forest management policies have decimated the state’s timber industry, neglected its biomass industry, rejected the cattle industry, turned millions of acres of forest into scorched earth, and are systematically turning mountain communities into ghost towns.

If the goal was to have a healthy forest ecosystem, that was violated, as these forests burned to the ground and what remains is dying. If the goal was to do anything in the name of fighting climate change and its impact on the forests and do it with urgency, that too was violated, because everything they did was wrong. Even now, instead of urgent and far-reaching changes to forest management policies, we get more electric car mandates. That was the urgent response to the superfires of 2020.

California’s ruling elites, starting with Gavin Newsom among the politicians, and Ramon Cruz, the Sierra Club’s new president, may prove they care about the environment by sitting down with representatives from California’s timber, biomass energy, and cattle industries, along with federal regulators, and come up with a plan. They might apply to this plan the same scope and urgency with which they so cavalierly transform our entire energy and transportation industries, but perhaps with more immediate practical benefits both to people and ecosystems.

This article originally appeared on the website American Greatness.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.