When it comes to water policy in California, perhaps the people are more savvy than the special interests. Because the people, or more precisely, the voters, by huge majorities, have approved nine water bonds in the past 25 years, totaling $27.1 billion. It is likely they’re going to approve another one this November for another $8.9 billion.

The message from the people is clear. We want a reliable supply of water, and we’re willing to pay for it. But the special interests – or whatever you want to call the collection of politicians, unelected bureaucrats with immense power, and other stakeholders who actually decide how all this money is going to be spent – cannot agree on policy. A recent article in the Sacramento Bee entitled “Why San Francisco is joining Valley farmers in a fight over precious California water,” says it all. “Precious California water.” But what if water were so abundant in California, it would no longer be necessary to fight over it?

As it is, despite what by this time next year is likely to be $36 billion in water bonds approved by voters for water investments since 1996, the state is nowhere close to solving the challenge of water scarcity. As explained in the Sacramento Bee, at the same time as California’s legislature has just passed long overdue restrictions on unsustainable groundwater withdrawals, the political appointees on the State Water Resources Control Board are about to enact sweeping new restrictions on how much water agricultural and municipal consumers can withdraw from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.

This is a perfect storm, and every conservation, recycling and storage project currently funded or proposed will not make up the shortfall. In 2002, well before these new restrictions were being contemplated, the California Dept. of Water Resources issued an authoritative study, “Averting a California Water Crisis,” that estimated the difference between demand and supply at between two and six million acre feet per year by 2020. An impressive response from the public during the most recent drought, combined with some investment in water infrastructure has narrowed that gap. But the squeeze is ongoing, with tougher challenges and tradeoffs ahead.

Abundance vs Scarcity

When thinking about solutions to California’s water challenges, there is a philosophical question that has to be addressed. Is it necessary to persistently emphasize conservation over more supplies of water? Is it necessary to always perceive investments in more supplies of water as environmentally unacceptable, or is it possible to decouple, or mostly decouple, environmental harm from investment in more water supplies? Is it possible that the most urgent environmental priorities can be addressed by increasing the supply of water, even if investing in more water supplies also creates new, but lessor, environmental problems?

This philosophical question takes on urgent relevance when considering not only the new restrictions on water withdrawals that face Californians, but also in the context of another great philosophical choice that California’s policy makers have made, which is to welcome millions of new immigrants from across the world. What sort of state are we inviting these new residents to live in? How will we ensure that California’s residents, eventually to number not 40 million, but 50 million, will have enough water?

It is this reality – a growing population, a burgeoning agricultural economy, and compelling demands to release more water to threatened ecosystems – that makes a grand political water bargain necessary for California. A bargain that offers a great deal for everyone – more water for ecosystems, more water for farmers, more water for urban consumers – because new infrastructure will be constructed that provides not incremental increases, but millions and millions of acre feet of new water supplies.

The good news? Voters are willing to pay for it.

How to Have it All – A Water Infrastructure Wish List

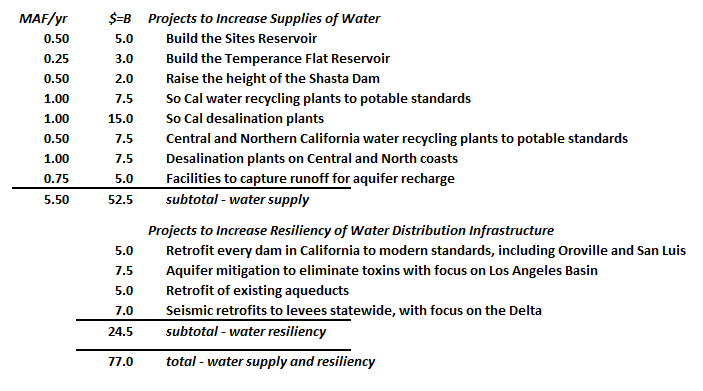

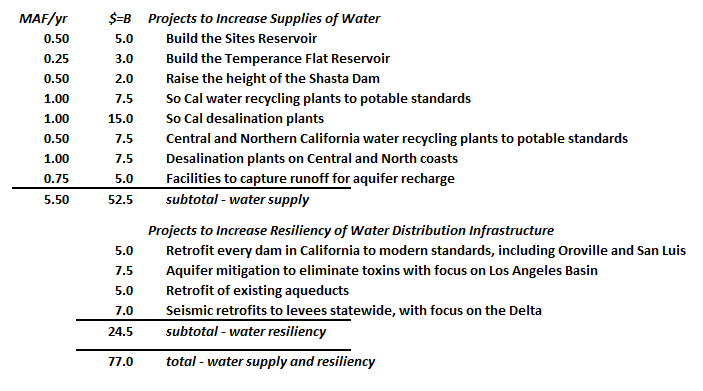

When considering what it would take to actually have water abundance again in California, the first step is to try to determine the investment costs, imagining a best case scenario where every good idea got funded. Here’s a stab at that list, not differentiating between local, state and federal projects. These are very approximate numbers, rounded upwards to the nearest billion:

Projects to Increase Supplies of Water

(1) Build the Sites Reservoir (annual yield 0.5 MAF) – $5.0 billion.

(2) Build the Temperance Flat Reservoir (annual yield 0.25 MAF) – $3.0 billion.

(3) Raise the height of the Shasta Dam (increased annual yield 0.5 MAF) – $2.0 billion.

(4) So Cal water recycling plants to potable standards with 1.0 MAF capacity – $7.5 billion.

(5) So Cal desalination plants with 1.0 MAF capacity – $15.0 billion.

(6) Desalination plants on Central and North coasts with 0.5 MAF capacity – 7.5 billion

(7) Central and Northern California water recycling plants to potable standards with 1.0 MAF capacity – $7.5 billion.

(8) Facilities to capture runoff for aquifer recharge (annual yield 0.75 MAF) – $5.0 billion.

Total – $52.5 billion.

Projects to Increase Resiliency of Water Distribution Infrastructure

(9) Retrofit every dam in California to modern standards, including Oroville and San Luis – $5.0 billion.

(10) Aquifer mitigation to eliminate toxins with focus on Los Angeles Basin – $7.5 billion.

(11) Retrofit of existing aqueducts – $5 billion.

(12) Seismic retrofits to levees statewide, with a focus on the Delta – $7 billion.

Total – $24.5 billion.

The total of all these projects, $77 billion, is not accidental. That happens to be the latest best case, low-ball estimate for California’s completed high speed rail project. Without belaboring the case against high speed rail, two comparisons are noteworthy.

First, an ambitious program to create water abundance in California and water infrastructure resiliency in California based on this hypothetical budget is achievable. These numbers are deliberately rounded up, and the final costs might actually be lower, whereas it is extremely unlikely that California’s high speed rail project can be completed for $77 billion.

Second, because people will actually consume these new quantities of water that are being supplied and delivered, private financing will be attracted to significantly reduce the taxpayer’s share.

The Impact of a $77 billion Investment on Water Supply, Resiliency, and Ecosystems

As itemized above, at a capital cost of $52.5 billion, the total amount of water that might be added to the California’s statewide annual water budget is 5.5 million acre feet.

This amount of water would have a staggering impact on the demand vs. supply equilibrium for water. It is nearly equal to the total water consumed per year by all of California’s urban centers. Implementing this plan would mean that nearly all of the water that is currently diverted to urban areas could be instead used to ensure a cool, swift flow in California’s rivers, while preserving current allocations for agriculture. The options for environmentalists would be almost unbelievable. Restore wetlands. Revive the Delta. Refill the shrinking Salton Sea.

The environmentalist arguments against the three dams are weak. Shasta Dam is already built. The impact of expanding the Shasta Dam is purportedly the worst on McCloud creek, where it will affect “nearly a mile” of what was “once a prolific Chinook salmon stream,” (italics added). That negative impact, which seems fairly trivial, has to be balanced against the profound benefit of having another 500,000 acre feet of water available every summer to generate pulses of swift, cool water in the Sacramento River. The proposed Temperance Flat Reservoir is proposed on a stretch of the San Joaquin River that already has a smaller dam. The Sites Reservoir is an offstream reservoir that will not interfere with the Sacramento River.

The environmental benefits of these dams are not limited to their ability to ensure supplies of fresh water for California’s aquatic ecosystems. They can also be used to store renewable electricity, by pumping water from a forebay at the foot of the dam into the reservoir during the day, when solar energy already brings the spot price of electricity down to just a few cents per kilowatt-hour, then generating hydro-electric power later in the evening when peak electrical demand hits the grid. This well established technology has already been implemented on dams throughout California, and remains one of the most cost-effective ways to store clean, but intermittent, renewable energy. It will also be a profit center for these dams.

The environmentalist arguments against desalination are also weak. The energy required to desalinate seawater is comparable to the energy necessary to pump it from Northern California to the Los Angeles Basin. The outfall can be discharged under pressure a few miles from shore, where it is instantly disbursed in the California current. The impact from the intakes is grossly overstated by environmentalists, when considering that even if all of these contemplated desalination plants were built, the water they would intake is only a fraction of the amount of water taken in for decades by California’s power plants that are sited on the coast and use seawater for cooling.

As for the Delta, the primary environmental threat to that ecosystem is the chance that an earthquake destroys the hundreds of miles of levees, causing the agricultural areas behind those levees to be flooded. Not only would agricultural contaminants enter the water of the Delta, but the rush of water flooding into the areas behind the levees would cause salt water from the San Francisco Bay to rush in right behind, creating conditions of salinity that would take years to remove, if ever.

This is why investing in levee upgrades and a Delta Smelt hatchery is a preferable solution to the Delta tunnels. The tunnels would ensure a resilient supply of water from north to south, but the Delta would still be vulnerable to levee collapse. Levee upgrades and a Delta Smelt hatchery would accomplish both goals – resiliency of the water supply and of the Delta ecosystem. Moreover, the presence of massive water recycling and desalination facilities in Southern California would take a great deal of pressure off how much water would need to be transported through the Delta from north to south.

How to Finance $77 Billion for Water Infrastructure

Funding capital projects depends on three possible sources: operating budgets, general obligation bonds, or revenue bonds. Operating budgets, which used to help pay for capital projects, and which ought to help pay for capital projects, will never be balanced until real pension reform occurs. So for the most part, operating budgets are not a source of funds.

A useful way to differentiate between general obligation bonds and revenue bonds are that the general obligation bonds impose a progressive tax on Californians, since wealthy individuals pay about 60% of all tax revenues in California. Revenue bonds, on the other hand, because they are serviced through sales of, for example, water produced by a desalination plant, are regressive. This is because all consumers see these costs included in their utility rates, and utility bills constitute a far greater proportion of the budget for a low income household.

The Grand Bargain – Creating Water Abundance in California

(MAF = million acre feet)

By financing water infrastructure through a combination of revenue bonds and general obligation bonds, instead of solely through revenue bonds, water can remain affordable for ordinary Californians. The $24.5 billion portion of the $77.0 billion wish list, the funds for dam, aqueduct, and levee retrofits, along with aquifer mitigation, are not easily serviced through revenue bonds. A 30 year general obligation bond for $24.5 billion with an interest rate of 5% would cost California’s taxpayers $1.6 billion per year. Some of these projects, to the extent they are improving water delivery to specific urban and agricultural consumers, might be funded by bond issuances that would be serviced by the agencies most directly benefiting.

To claim that 100% of the revenue producing water projects can be financed through revenue bonds is more than theoretical. The Carlsbad Desalination Plant financing costs, principle and interest payments a nearly $1.0 billion for the plant’s construction, are paid by the contractor that built and operates the plant, with those payments in-turn funded through the rates charged to the consumers of the water. The contractor also retains an equity stake in the project, meaning that additional capital costs incurred privately are also funded via a portion of the rates charged to consumers.

Some of the revenue producing assets on the grand bargain wish list may also have a portion of them paid for by general obligation bonds. Determining that mix depends on the consumer. For example, a revenue bond for the reservoir projects may be applied to agricultural consumers who are willing to pay well above historical rates to have a guaranteed source of water for their orchards, which have to survive through dry years.

For urban consumers in particular, making the more expensive projects financially palatable may require general obligation bonds to cover part of the costs, so the remaining costs are affordable for ratepayers. For example, desalination is a relatively expensive way to produce water, making it harder to finance 100% with revenue bonds. But without desalination, wastewater recycling and runoff capture are not sufficient local sources of water in places like Los Angeles. The overall benefit to Californians of adding another 1.5 million acre feet per year to the state’s water supply, using desalination which is impervious to droughts, may be worth having some of its cost financed with general obligation bonds.

To fund roughly 50% of the revenue producing water supply infrastructure ($26.2 billion) and 100% of the water resiliency and distribution infrastructure ($24.5 billion) on this list would cost taxpayers about $3.0 billion per year. While this might strike some as an unthinkable amount to even consider, these projects meet all the criteria for so-called “good debt.” Constructing them all would solve California’s challenge of water scarcity, possibly forever. All of the projects are assets yielding ongoing and long-term benefits that will outlast the term of the financing. At the same time, water would become so abundant in California that prioritizing water allocations to revive ecosystems would no longer provoke bitter opposition. And California’s residents would live again in a state where taking a long shower, planting a lawn, and doing other water-intensive activities that are considered normal in a developed nation, would once again become affordable and normal.

Other Ways to Help Pay for Water Abundance in California

Enable and Expand Water Markets

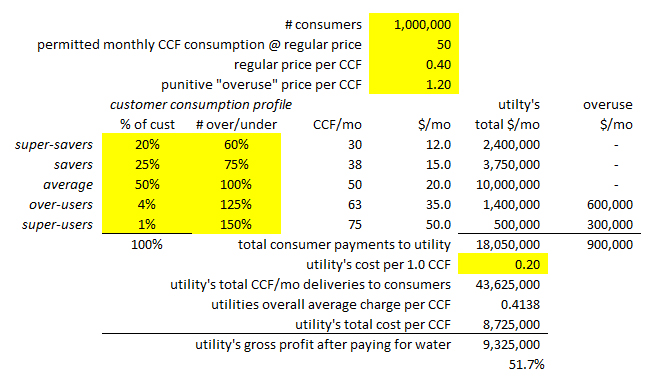

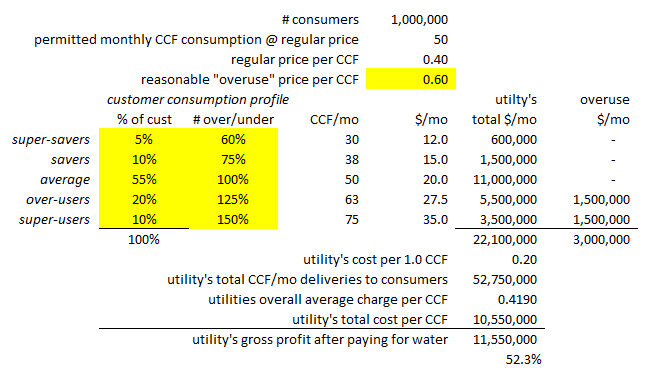

Even if a grand bargain is struck between environmentalists, farmers, and water districts, and massive investments are made to increase the supply of water, enabling and expanding water markets will help optimize the distribution of available water resources. Similarly, reforming California’s labyrinthine system of water rights might also help, by making it easier for owners of water rights to sell their allocations. Fostering water markets while protecting water rights have interrelated impacts, and ideally can result in more equitable, appropriate water pricing across the state. It might also help make it unnecessary to impose punitive tiered rates or rationing on household consumers.

Reform Environmentalist Barriers to Development

CEQA, or the California Environmental Quality Act, is a “statute that requires state and local agencies to identify the significant environmental impacts of their actions and to avoid or mitigate those impacts, if feasible.” While the intent behind CEQA is entirely justifiable, in practice it has added time and expense to infrastructure projects in California, often with little if any actual environmental benefit. An excellent summary of how to reform CEQA appeared in the Los Angeles Times in Sept. 2017, written by Byron De Arakal, vice chairman of the Costa Mesa Planning Commission. It mirrors other summaries offered by other informed advocates for reform and can be summarized as follows:

- End duplicative lawsuits: Put an end to the interminable, costly legal process by disallowing serial, duplicative lawsuits challenging projects that have completed the CEQA process, have been previously litigated and have fulfilled any mitigation orders.

- Full disclosure of identity of litigants: Require all entities that file CEQA lawsuits to fully disclose their identities and their environmental or, increasingly, non-environmental interest.

- Outlaw legal delaying tactics: California law already sets goals of wrapping up CEQA lawsuits — including appeals — in nine months, but other court rules still leave room for procedural gamesmanship that push CEQA proceedings past a year and beyond. Without harming the ability of all sides to prepare their cases, those delaying tactics could be outlawed.

- Prohibit rulings that stop entire project on single issue: Judges can currently toss out an entire project based on a few deficiencies in environmental impact report. Restraints can be added to the law to make “fix-it ticket” remedies the norm, not the exception.

- Loser pays legal fees: Currently, the losing party in most California civil actions pays the tab for court costs and attorney’s fees, but that’s not always the case with CEQA lawsuits. Those who bring CEQA actions shouldn’t be allowed to skip out of court if they lose without having to pick up the tab of the prevailing party.

Find Other Ways to Reduce Construction Costs

The Sorek desalination plant, commissioned in Israel in 2015, cost $500 million to build and desalinates 185,000 acre feet of water per year. Compared to Carlsbad, which also began operations in 2015, Sorek came online for an astonishing one-sixth the capital cost per unit of capacity. Imagine if the prices Israelis pay to construct desalination plants could be achieved in California. Instead of spending $15 billion to build 1.0 million acre feet of desalination capacity, we would spend less than $3.0 billion. How did they do this?

The bidding process itself adds unnecessary costs to public infrastructure projects. Moving to a design-build process could significantly reduce duplicative work during the plant’s engineering phase. Project labor agreements are another practice that at the very least deserve serious reconsideration. Would it be possible objectively evaluate the impact of project labor agreements, and determine to what extent those mandates increase costs?

What about economies of scale? If ten desalination plants were commissioned all at once, wouldn’t there be an opportunity for tremendous unit savings? What about creativity? Elon Musk, who has disrupted the aerospace industry by building rockets at a fraction of historical prices, said “the construction industry is one of the only sectors in our economy that has not improved its productivity in the last 50 years.” Is he even partly correct? Is that worth looking into?

Shift Government Spending Priorities

Cancel High Speed Rail: The most obvious case of how to redirect funds away from something of marginal value into water infrastructure, which is something with huge public benefit, is to cancel the bullet train. The project is doomed anyway, because it will never attract private capital. But what if Californians were offered the opportunity to preserve the planned bond issuances for high speed rail, tens of billions of capital, but with a new twist? If voters were asked to redirect these funds away from high speed rail and instead towards creating water abundance through massive investment in water infrastructure, there’s a good chance they’d vote yes.

Cancel the Delta Tunnels: By investing in levee hardening, the Delta’s ecosystems can be fortified against a severe earthquake. Reducing the possibility of levee failure protects the Delta ecosystems from their worst environmental threat at the same time as it protects the ability to transfer water from north to south. Investing in hatcheries to increase the population of the threatened Smelt is a far more cost-effective way of safeguarding the survival of that species. And investing in infrastructure on the Southern California coast to make that region water independent greatly reduces the downside of a disruption to water deliveries through the Delta. Canceling the Delta Tunnels would save $20 billion, money that would go a long way towards paying for other vital water infrastructure.

Reform Pensions: The biggest out of control budget item, by far among California’s state and local agencies, is the cost of public sector pensions. A California Policy Center analysis released earlier this year, based on public announcements from CalPERS, estimated that the total employer payments for pensions for California’s state and local government employees is set to nearly double, from $31 billion in 2018 to $59 billion by 2024. And that is a best case baseline. If there is a severe market correction, those required contributions will go up further. No discussion of how to find money for other government operations can take place without understanding the role of pension costs in creating budget constraints.

Reduce State Spending: Other ways to shift spending priorities in California, while worth a discussion, are mostly controversial. Returning the administrator to faculty ratio in California’s UC and CalState systems to its historical level of 1:2 instead of the current 1:1 would also save $2.0 billion per year. Outsourcing CalTrans work and eliminating redundant positions could save $2.5 billion per year. Reducing just state agency headcount and pay/benefits by 20% would save $6.5 billion per year. Just enacting part of that, incremental pension reform for state workers, could stop the runaway cost increases that are otherwise inevitable.

California’s state budget this year has broken $200 billion for the first time. Of that, general fund spending is at $139 billion, also a record. Revenues, however, have set records as well. The rainy day fund is full, and an extra deposit of $2.6 billion has it overflowing. Why not spend that $2.6 billion on water infrastructure? For that matter, why not spend all of the $1.4 billion of cap and trade revenue on water infrastructure?

Financing more water infrastructure will more likely come via public and private debt financing. But redirecting intended future borrowings, in particular for high speed rail and for the Delta Tunnels, could cover most if not all of the infrastructure investments necessary to deliver water abundance to Californians. And at the least, redirecting funds from government operating budgets can defray some of the operating costs, if not some of the capital costs.

Work to Build a Consensus

How many more times will California’s voters approve multi-billion dollar water bonds? The two passed in the last four years, plus the current one set for the November ballot, raise $20 billion, but only $2.5 billion of that goes to reservoir storage. Only another $3.3 billion more goes to any type of supply enhancements – mostly to develop aquifer storage or fund water recycling. Meanwhile, consumers are being required to submit to permanent water rationing, and dubious projects are being funded to save water. Artificial turf is a good example. There isn’t a coach in California who wants their athletes to compete on these dangerous surfaces. On a hot day in Sacramento, the temperature on these “fields” can reach 150 degrees. They are actually keeping sprinkler systems operating on these horrendous boondoggles, just to reduce the deadly heat buildup.

Credibility with voters remains intact to-date, but cannot be taken for granted. If a grand bargain on California’s water future is struck, it will need to promise, then deliver, water abundance to California’s residents.

Change the Conventional Wisdom

California’s current policies have stifled innovation and created artificial scarcity of literally every primary necessity – not just water, but housing, energy and transportation. Each year, to comply with legislative mandates, California’s taxpayers are turning over billions of dollars to attorneys, consultants and bureaucrats, instead of paying engineers and heavy equipment operators to actually build things. The innovation that persists despite California’s unwelcoming policy environment is inspiring.

California’s policymakers have adhered increasingly to a philosophy of limits. Less water consumption. Less energy use. Urban containment. Densification. Fewer cars and more mass transit. But it isn’t working. It isn’t working because California has the highest cost of living in the nation. Using less water and energy never rewards consumers, because the water and energy never were the primary cost within their utility bills – the cost of the infrastructure and overhead was the primary cost.

Changing the conventional wisdom applies to much more than water. It is a vision of abundance instead of scarcity that encompasses every vital area of resource consumption. A completely different approach that could cost less than what it might cost to fully implement scarcity mandates. An approach that would improve the quality of life for all Californians. Without abandoning but merely scaling back the ambition of new conservation and efficiency mandates, embrace supply oriented solutions as well. Build wastewater recycling and desalination plants on the Pacific coast, enough of them to supply California’s massive coastal cities with fresh water. Instead of mandating water rationing for households, put the money that would have been necessary to retrofit all those homes into new ways to reuse water and capture storm runoff.

Paying for all of this wouldn’t have to rely exclusively on public funds. Private sector investment could fund a large percentage of the costs for new water infrastructure. Water supplies could be even more easily balanced by permitting water markets where farmers could sell their water allotments without losing their grandfathered water rights. If the bidding process and litigation burdens were reduced, massive water supply infrastructure could be constructed at far more affordable prices.

The Grand Bargain

Water abundance in California is achievable. The people of California would welcome and support a determined effort to make it a reality. But compromise on a grand scale is necessary to negotiate a grand bargain. Environmentalists would have to accept a few more reservoirs and desalination plants in exchange for plentiful water allocations to threatened ecosystems. Farmers would have to pay more for water in exchange for undiminished quantities. While private financing and revenue bonds could cover much of the expense, taxpayers would bear the burden of some new debt – but in exchange for permanent access to affordable, secure, and most abundant water.

This is the third and final part of an investigation into California’s water future. Part one is “How Much California Water Bond Money is for Storage?,” and part two is “How to Make California’s Southland Water Independent for $30 Billion.” Edward Ring is a co-founder of the California Policy Center and served as its first president.

* * *

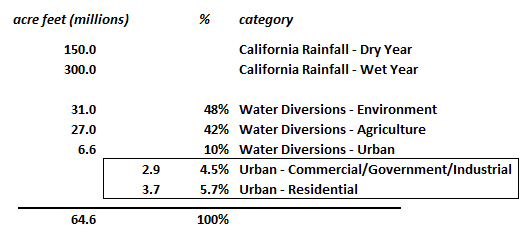

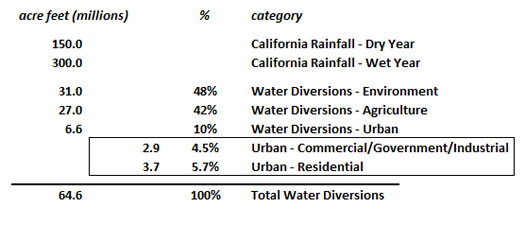

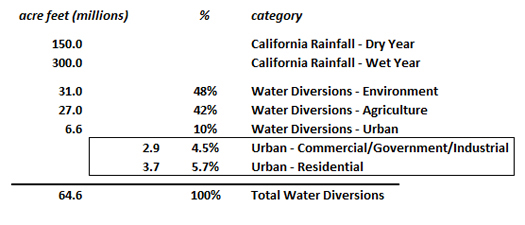

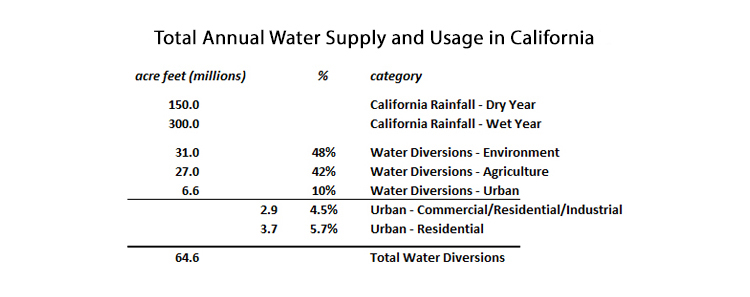

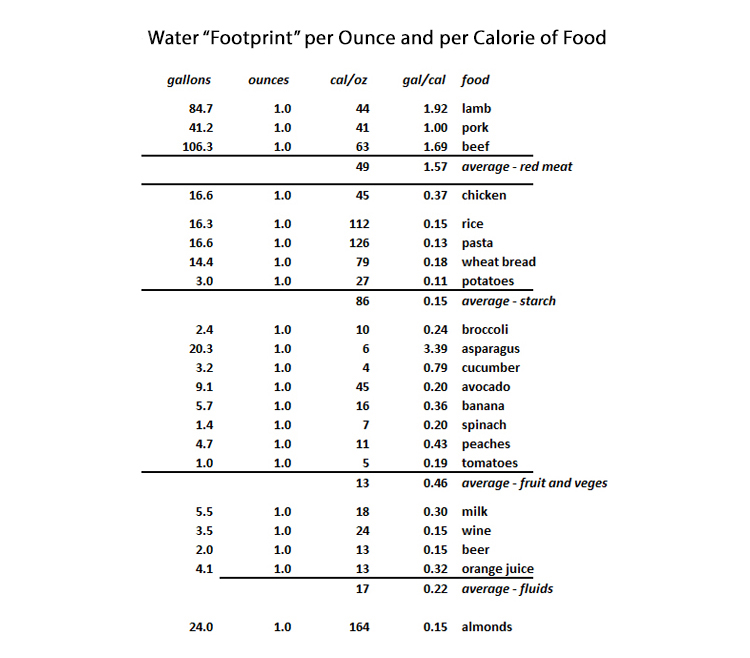

Armed with these facts, there’s a strong argument that cutting back on residential water consumption will not make a significant difference in California’s overall water use. There are additional facts that can put this argument into an even sharper context: How much water do California’s households consume in terms of the water that was required to grow the food they eat, and how does that amount compare to the water they purchase from their utility for indoor/outdoor use?

Armed with these facts, there’s a strong argument that cutting back on residential water consumption will not make a significant difference in California’s overall water use. There are additional facts that can put this argument into an even sharper context: How much water do California’s households consume in terms of the water that was required to grow the food they eat, and how does that amount compare to the water they purchase from their utility for indoor/outdoor use?

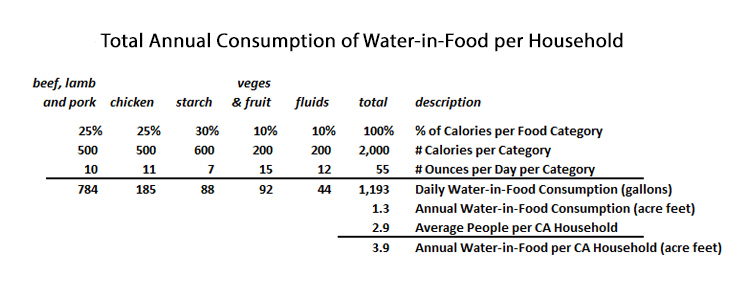

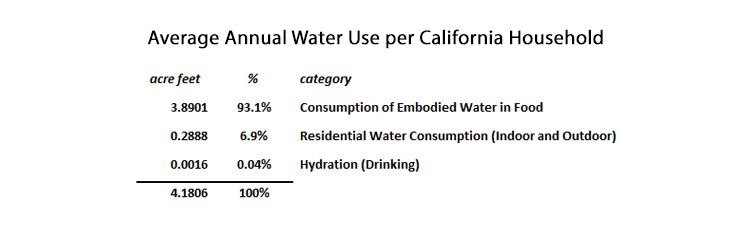

To summarize, in one year, the average American consumes a quantity of food that required 1.3 acre feet of water to grow. In turn, at 2.91 people per household in California, the average household consumes a quantity of food per year that requires 3.9 acre feet of water to grow.

To summarize, in one year, the average American consumes a quantity of food that required 1.3 acre feet of water to grow. In turn, at 2.91 people per household in California, the average household consumes a quantity of food per year that requires 3.9 acre feet of water to grow. There is no Reason Water Cannot be Abundant and Affordable

There is no Reason Water Cannot be Abundant and Affordable