The Abundance Choice (part 4) – Crafting a Water Initiative

To be fair, Assemblyman Devon Mathis didn’t come up with the idea of allocating a percentage of the state budget to accomplish a policy priority. He got that idea from the California Teachers Association, which in 1988 convinced voters to approve a constitutional amendment that required a minimum of 40 percent of California’s general fund to be spent on K-14 education. But Mathis did have the temerity to be one of the first legislators to emulate the concept when, in 2019, he introduced to the state assembly the “Clean Water for All Act,” which would have given voters a chance to allocate another slice of the general fund to a specific purpose, in this case, funding water infrastructure.

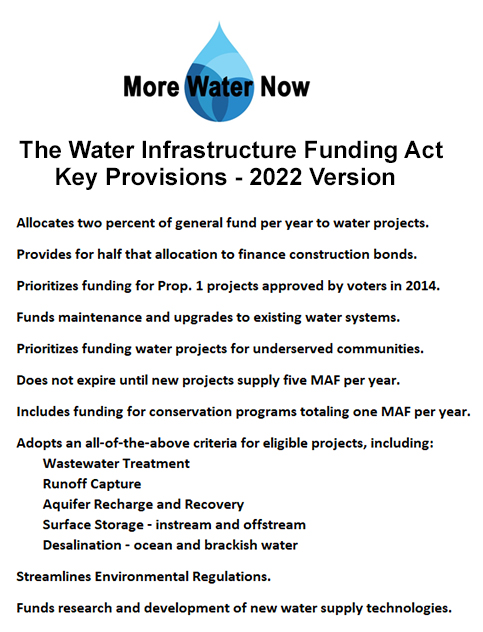

Assembly Constitutional Amendment 3 died in committee, but the precedent was set. Ballot box budgeting was back in play. When I talked with Mathis about our initiative in July 2021, it was clear that water was still a top priority for this moderate Republican from the San Joaquin Valley. And as soon as he brought up the “two percent solution,” I knew we had something we could run with.

Up to that point, we had been on the right track with our focus on getting funding for projects that would increase the supply of water to Californians, but we had been planning for the initiative to rely on bond financing. The problem with this approach was that the amount we estimated California needs to spend on water infrastructure starts at around $50 billion, and voters have never approved a bond at anywhere near that amount. Two percent of the state general fund, on the other hand, sounded like a reasonable amount, if not a pittance. After all, for a mere two percent of the state general fund, water scarcity in California would be eliminated forever.

These numbers were big. And they worked. In July 2021, the state general fund budget was projected at $196 billion for the 2021-22 fiscal year. Two percent of that would be $4 billion per year. And here is where we decided to add some creativity, by providing for half of that $4 billion, or one percent of the general fund, to be used to pay principal and interest on bonds. At four percent interest spread over 30 years, that would unlock $35 billion in immediate funding. Even at five percent over 20 years, the state would have immediate access to $25 billion.

These amounts would be sufficient to allow the state to begin funding several major projects at once. They would be sufficient to permit the state to provide 100 percent funding to projects of statewide benefit where local matching funds were not available, but there would also be plenty left over to fill in the required funding where the local or regional partners had raised a significant portion of the project cost but couldn’t fully fund it on their own. And while this $2 billion per year would be committed to financing $25 to $35 billion in bond funding, there would still be the other half of the two percent stream, another $2 billion per year, available to fund hundreds of smaller projects and fill in wherever needed.

Uniting Farmers and Urban Water Agencies

The steering committee we formed included people from urban water agencies as well as from agriculture. One of the founding members was Kristi Diener, part of a farm family in the San Joaquin Valley who now have to cope with unprecedented water scarcity. The Facebook group that Kristi founded, California Water for Food and People, has a mission “To unite in one place all of California’s water-for-food-and-people advocates, coalitions, organizations, groups, bureaus, alliances, growers, etc. wishing to come together to form one large action force, to compel immediate long term solutions to protect and provide water for humans.” With over 24,000 members, for several years they have been sharing information and educating the public and politicians on the topic of water policy. Kristi was one of the first people I called, and together we recruited several other participants.

Other notable steering committee participants included three experienced urban water agency executives and directors based in Southern California: Steve Sheldon, president of the Orange County Water District, Lisa Ohlund, recently retired general manager of the Eastern Municipal Water District who now consults for several water agency clients, and Shawn Dewane, vice president of the Mesa Water District. Three more members of the farming community were significant participants, including Martin Chavez, a member of a multigenerational farming family, and a board director of the Stratford Public Utilities District, Wayne Western Jr., the general manager of the Hammonds Ranch which is located in the absolute heart of the San Joaquin Valley, and Geoff Vanden Heuvel, director of regulatory and economic affairs at the California Milk Producers Council.

Getting this group together on one steering committee, along with others, insofar as they represented farming interests on one hand and Southern California urban water district interests on the other, was itself an accomplishment. These groups do not necessarily see eye to eye on which water policies and water projects should be prioritized in California. But within our committee, there was strong agreement. Everyone saw the urgency of the challenge California faces, even if the politicians and water bureaucrats in Sacramento still do nothing but ratchet up rationing and hope for rain. Our goal was to come up with an initiative that would create water abundance.

We recognized early on that if we consistently maintained a statewide perspective that treated water as fungible, that would make agreement on an initiative much easier. From a statewide perspective, if an urban water recycling project results in 250,000-acre-feet per year of wastewater being reused, that means 250,000-acre-feet of water elsewhere in California no longer has to be diverted and imported via aqueduct into that urban area. Similarly, if an off-stream reservoir captures storm runoff and yields another 250,000-acre-feet of water each year for farmers, that frees up 250,000-acre-feet that can be available for urban use or, for that matter, released into rivers for ecosystem health.

Another fundamental provision our committee agreed on very early was to build a sunset provision into the two percent mandate. Once new water projects were supplying 5 million acre-feet of water per year, the two percent allocation would go away. We stipulated that these new projects could be funded entirely without any money from the general fund, or make exclusive use of general fund allocations. What mattered was that new water infrastructure projects would yield 5 million-acre-feet of additional water to Californians. We didn’t care how they would be paid for.

Between July and September 29, 2021, when our final amended version of the initiative was turned in to the California attorney general, we worked nonstop on crafting this initiative. We regularly emailed updated drafts to a list of experts around the state that grew to more than 300 recipients. The initiative went through 12 full revisions and countless minor revisions, and we worked hard to cover all eventualities. Among the hundreds of experts we talked with, many scenarios were shared. As these mostly cautionary what-ifs piled up, the provisions we added piled up commensurately.

For example, we added a redefinition of “beneficial use,” stipulating that it would include urban and agricultural use and not be restricted to environmental benefits. We stipulated that the water supplied from new projects would only count towards the 5 million-acre-foot goal if it was for agricultural and urban use. We also stipulated that any new government regulations that further restricted groundwater or river withdrawals—or demolition of water-yielding assets such as reservoirs—would trigger a proportional increase to the 5 million-acre-foot per year goal.

An “All of the Above” Approach to More Water

Finally, we agreed that it was important to keep all water supply solutions within the project categories eligible for funding, and instead of picking specific projects, we carefully defined the eligible categories. These included projects to expand reservoirs, build new reservoirs, wastewater recycling plants, desalination plants, as well as facilities for runoff capture, and aquifer recharge and recovery. Also included were the conveyances—new or upgraded pipelines and aqueducts—necessary to transport this new water from source to consumer.

In one concession to picking specific projects, and out of respect both for the will of the voters and the many people around the state who had relied on this going through and been let down, we specified that the top priority for funding would be those water storage projects approved by voters in 2014. As previously noted, $2.7 billion was allocated for those projects, including the desperately needed Sites Reservoir, and as of May 2022, not one of them has yet broken ground.

There was much more. In our discussions with board members and executives at water agencies, the giant Metropolitan Water District of Southern California in particular, we agreed that 1 million of the 5 million-acre-feet goal could be achieved through making funds available for additional urban and agricultural conservation programs. We believed this was an appropriate compromise, since it acknowledged that conservation still has a vital role to play in solving California’s water crisis, but still preserved 80 percent of the goal—4 million acre-feet of additional water per year from new water supply projects.

The folks at Met, and others, suggested we include priority funding for disadvantaged communities. We not only added that as a priority criterion for which projects that conformed to the eligible project categories would first receive funding, but we modified our project categories. In addition to the categories explicitly defined to increase the supply of water—groundwater recharge and recovery, wastewater and stormwater reuse and recycling, upgrading existing and constructing new reservoirs, and desalination—we added the following:

“(5) Water conveyance development, maintenance, or expansion, for the delivery of clean, safe drinking water for homes and businesses, and water for agricultural uses consistent with area-of-origin water rights;

(6) Other projects designed to increase the clean, safe and affordable supply of water to all Californians with emphasis on California’s disadvantaged communities, and other projects designed to increase conservation.”

The promise embodied in these two additions cannot be overstated. With these new categories included, urgently needed projects that lack any hope of getting rapid access to adequate funds could be built. One compelling example is the more than 400 small towns and school districts in California that do not have access to safe drinking water. Another is the need to replace the toxic pipes in the older schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District. That project will cost tens of millions—if not more—and they have no idea where they are going to get the money to do it.

This is a brief summary of what we came up with. There was much more to this initiative that weighed in at 8,071 words when completed. It is unlikely it could have achieved our objectives if it had been any shorter. We had engaged a lead attorney with extensive experience in California constitutional law and specifically in writing ballot initiatives. During the research phase prior to our campaign launch, various attorneys reviewed his work, all of them expert volunteers, involved in farming, water policy, water agencies, construction unions, and construction contractors.

The length of the initiative was dictated by the necessity to include a constitutional amendment component in order to, among other things, allocate two percent of the state general fund to water projects, and a statutory component in order to allow half of that money to be used to pay principle and interest on new water bonds. Other lengthy sections were necessary to include modifications to the Coastal Act and the California Environmental Quality Act, without which we were convinced this initiative would sail straight into gridlock just like Proposition 1 has for the past eight years, making all the trouble of gathering voter approval worthless. And then there was the actual meat of the initiative, the definitions of eligible project categories. Despite its length, this long-winded initiative was, and is, a highly refined product.

In subsequent installments the reasons for what we came up with, and why, to address concerns and objections from labor unions, environmentalists, and various and often competing farming interests. But throughout the process, we adhered to a few fundamental guiding principles: The policies necessary to solve urban water challenges and farming water challenges are not mutually exclusive. A statewide perspective is essential, and state funding should support projects to the extent local ratepayers cannot cover the costs. Conservation is not enough, and it is time now to spend tens of billions of dollars to bring California’s water infrastructure, still the marvel of the world, into the 21st century.

This article originally appeared on the website of the California Globe.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.