California’s Personnel Costs

Over the past twenty years, as wages in the private sector have remained pretty much flat – not even keeping up with inflation – wages in the public sector have risen relentlessly. A generation ago, a public sector worker would sacrifice current pay for job security and a pension that was somewhat better than social security, but today, not only are public employee pension benefits far more generous than they used to be, but public employees generally make more in current pay than their private sector counterparts. While this assertion remains hotly debated, one seeking the truth might consider this comment – made in a guest column in the San Francisco Chronicle earlier this month – by former California Assembly Speaker Willie Brown:

“The deal used to be that civil servants were paid less than private sector workers in exchange for an understanding that they had job security for life,” Brown asserted. “But we politicians — pushed by our friends in labor — gradually expanded pay and benefits . . . while keeping the job protections and layering on incredibly generous retirement packages. . . . This is politically unpopular and potentially even career suicide . . . but at some point, someone is going to have to get honest about the fact.”

If Willie Brown, a friend of big government and big labor if there ever was one, is on record with a comment like this, it’s time to move on. Personnel costs for government employees have grown out of proportion to private sector compensation, and California is perhaps the most extreme example. Another question that requires clarity is exactly what percentage of government budgets are consumed by personnel costs? Clearly this is a figure of vital importance, because if personnel costs represent an insignificant share of California’s budget, there is far less urgency to restore the historic trade-off that is supposed to apply when you join public service, i.e., you receive lower current pay in exchange for higher retirement security.

In the table below, California’s state and local personnel costs are calculated using the most recent data available from the U.S. Census Bureau, and compiled by USGovernmentSpending.com. The first thing that should be readily evident is most of California’s government spending is at the county and city level, since of the $516 billion reported for 2009, only $138 billion of that is state spending, and the other $321 billion is local spending. The implications of this fact are ominous – less than 1/3rd of California’s structural budget deficits are caused at the state level.

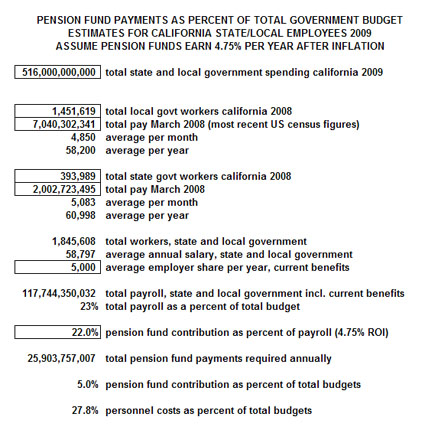

In order to determine the percentage of this half-trillion of state and local spending in California that is consumed by payroll, turn to the U.S. Census Bureau’s California statistics directly for 2008 Public Employment Data, Local, and 2008 Public Employment Data, State. These tables, updated in December 2009, yield both the number of state and local government employees in California and their total payroll, not including current benefits or pension funding. Assuming an average cost for current benefits of $5,000 per year per full-time employee (probably grossly understated), the total payroll of state and local governments in California is $188 billion per year, or 23% of total spending. What about pension funding?

In a previous post, Maintaining Pension Solvency, the amount necessary to fund a typical state worker pension is calculated using four sets of assumptions – based on a public safety pension plan (assuming 90% of final pay as the retirement pension) and based on a regular non-safety public employee pension plan (assuming 60% of final pay as the retirement pension), with each of these cases calculated based on an inflation adjusted rate of return on the pension fund investments of 4.75% (CalPERS official rate used for projections), and 3.00% per year (a more conservative rate). The table below uses a rate of return of 4.75% per year, and takes into account census data which indicates 13% of Calfornia’s state and local government employees are in public safety, and the other 87% are not, in order to calculate the percent of payroll that must be allocated to pensions. In this case, 23% of payroll, or 5.0% of total government spending, must be allocated to pension funding each year. In all, using these assumptions, 28% of of California’s total government spending is for personnel costs.

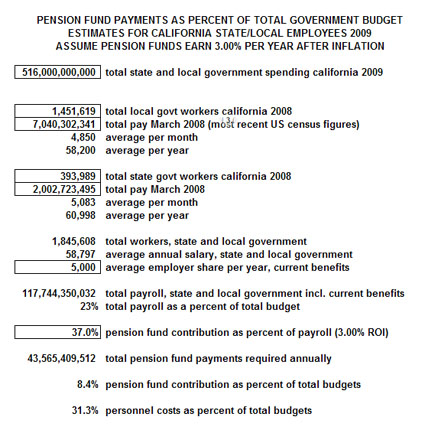

What if pension funds don’t return 4.75% per year, but only average 3.0%? Or what if they do average 4.75%, but since they are so underwater currently, a greater than usual contribution must be made each year from now on anyway? The next table shows the result of calculations using a 3.0% return on pension fund investments. In this case, 37% of payroll, or 8.4% of total government spending, must be allocated to pension funding each year. In all, using these assumptions, 31% of of California’s total government spending is for personnel costs.

There is a lot to chew on here. If you calculate personnel costs as a percent of revenue, instead of as a percent of spending, for example, eliminating the roughly $100 billion dollar annual deficits that state and local budgets combined easily exceed in California, and you use the 3.0% inflation-adjusted return on investment for your pension fund, personnel costs swell to 39% of total state and local budgets. If you also assume the costs of current benefits are not $5,000 per year on average, but $10,000 per year (a figure which may still be on the low side), personnel costs swell to 42% of total state and local budgets. What about the current year funding requirements for future retirement healthcare benefits – a line-item cost only rivaled by pension funding requirements – only beginning to be discussed in the context of total annual costs for government workers. And if you take into account the amount of remaining expenditures that are “pass-throughs” to quasi-governmental agencies and contractors, many of whom constitute the last entities outside of government to have enjoyed regular cost-of-living increases over the past 20 years along with pension plans that dwarf social security in their generosity, the percentage of state and local spending that is represented by personnel costs probably doubles – pick a number. Better yet, let’s hear from Willie Brown again – quote:

“Talking about this is politically unpopular and potentially even career suicide for most officeholders. But at some point, someone is going to have to get honest about the fact that 80 percent of the state, county and city budget deficits are due to employee costs.”

If 80% of California’s government expenditures go to personnel costs (probably accurate if you include pass-throughs to contractors who also enjoy swollen pay and benefit packages), and the combined annual state and local budget deficits in California are $100 billion, then basic algebra might suggest the following solution: Reduce the $400 billion that California’s state and local governments spend annually on compensation – including all government-funded project labor agreements for infrastructure, and, for that matter, as a prerequisite to any organization receiving state and local funds – by 25% across the board, and you balance the budgets without compromising programs or raising taxes. How many workers in the private sector would love to have a job that paid them 75% of what they made during the bubble booms?

No matter how you fine-tune an analysis like this, some conclusions are unavoidable. There is a tremendous consequence to the fact that California’s state and local government expenditures for employee compensation, per employee, have grown dramatically over the past twenty years at the same time as private sector compensation has remained relatively flat. When reform advocates suggest rolling back the pay, benefits, and pension packages for public employees in order to eliminate deficits and preserve worthy government programs, they are not making spurious arguments based on anti-government bias, or anti-government employee bias. They have simply run the numbers, and recognized reality.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

When you said, “but today, not only are public employee pension benefits far more generous than they used to be, but public employees generally make more in current pay than their private sector counterparts.”

I have to disagree with you. In California some of the Civil Engineer working for the state has been paid a lot less than their counterparts work for city, county, and definitely private consulting firm. Their benefits has been trimmed.

I guess it all depends on which segment you are talking about.

“I have to disagree with you. In California some of the Civil Engineer working for the state has been paid a lot less than their counterparts work for city, county, and definitely private consulting firm. Their benefits has been trimmed.”

I thought working for the State gets you paid higher?

My father worked as an engineer for the state of Pennsylvania, definitely got paid less than he would in the private sector, but with all the benefits the total compensation package worked out to be more. And that’s not even counting the fact that he got to retire and keep bringing in about 90% of his pay before social security!