How Interest Rates Affect the Federal Budget

The relationship between stagnant economic growth and high levels of total market debt should be clear to anyone trying to manage a household where their home mortgage payment consumes 50% or more of their entire household income. Similarly, the relationship between economic growth and the ability to borrow should be clear to anyone who has enjoyed the ability to purchase anything and everything in sight right up until they reached the point where every credit card they owned was maxed, and every dime of home equity available to them was already borrowed and spent. These comparisons hold true at the macroscopic level as well.

In the case of the federal government, borrowing has been facilitated by the ability to borrow money at cheap rates of interest. According to the official website of the U.S. Treasury, the Total Outstanding Public Debt, i.e., the total amount of money currently owed by the U.S. federal government is $14.3 trillion. From the same source, the Interest Expense on the Debt Outstanding for the first 9 months of fiscal 2011 (through June 2011) is $389 billion, which equates to an annual expense of $519 billion. Does anyone see anything wrong with this picture? The U.S. federal government is only paying interest on its debt at a rate of 3.6%. What happens if this rate of interest goes up?

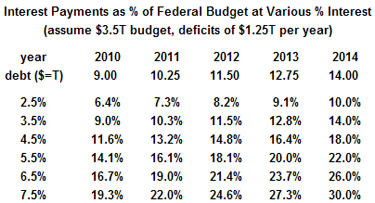

In the table below, the best case scenario is presented, since it excludes “Intragovernmental Holdings,” which is debt the federal government owes to other government agencies, which accounts for about a third of the total debt. If you account for payments on all 14.3 trillion of federal debt, the half-trillion that the federal government currently pays at a composite rate of 3.6% already consumes about 14% of the federal budget. And as the table indicates, for every 1.0% that the rate of interest goes up, interest payments consume an additional 3.0% of the federal budget. Back in the early 1980’s , the maximum 30 year treasury bill peaked at about 16%, so the extreme case in this table, 7.5%, is not far fetched.

A more sobering way to present this data might be to consider what percentage of government revenues (about $2.1 trillion) are consumed by interest payments on total government debt ($14.3 trillion), since currently the federal government only collects about 60% of what they’re spending. By this reasoning, at an interest rate of 3.5%, the federal government is paying 24% of every dollar it collects in taxes right back again in interest payments. That’s today, at low rates of interest. If the federal government had to pay 7.5% interest, today, then the federal government would pay just over 50% of every dollar it collects in taxes right back again in interest payments.

It is interesting to wonder if inflation can erode the principal value of the federal debt. Without presenting an avalanche of what-if spreadsheets, here are some of the problems with inflation as a panacea for debt: To the extent inflation increases government revenues to service debt, interest rates rise in parallel with the rate of inflation, meaning the amount of debt service goes up, offsetting the benefit of the diminished value of the principal. The only way these countervailing forces can end up favoring the borrower is if the real interest rates – i.e., the rate of interest less the rate of inflation – fall, but in the higher risk environment of an inflationary economy, real interest rates are likely to rise. More significantly is the fact that real interest rates are at all-time lows today. With inflation – official vs. unofficial – hovering somewhere between 2.0% and 5.0%, real interest rates on federal borrowing are arguably negative.

The problem with inflation as a cure for federal debt is also compounded by the fact that everyone’s trying it. For inflation to endure, currency must devalue, and every nation on earth – definitely including the Chinese whose debt problem is only obscured by their asset bubble – is determined to devalue their currency. Compared to the Europeans and the Chinese, the U.S. dollar remains quite durable, and is unlikely to devalue.

What could present itself in the next few years, because inflation not a very likely scenario, is that debt service becomes so burdensome for governments in the U.S., federal, state and local, that defaults begin to occur, which will require raising the risk premium in order to attract lenders, which will further add to the burden represented by payments on debt. The deflationary impact of unsustainable debt is the true boogeyman of the global economy, and is the reason they are burning up the printing presses down at the United States Mint to print more currency, and why the Federal Reserve Bank will keep interest rates as low as they can for as long as they can.

The cure for stagnant growth caused by maxed out debt is to lower the cost of living, which creates liquidity to eliminate debt and invest in new industries. This is precisely the opposite of what we are seeing stimulus money spent on. The powerful combination of environmentalist interests and government unions are blocking development of cheap energy, water storage, and abundant open land, which would lower the cost of the basic necessities of life – energy, water and shelter – and stimulate consumer spending and business expansion. Instead of building this infrastructure, they are spending stimulus money to maintain overmarket compensation and benefits for public employees, and “green jobs” whose only impact is to offer consumers products and services that cost more than existing conventional solutions. This is the path to a debt-fueled deflationary collapse, and there is an alternative.

Related posts:

The Razor’s Edge: Inflation vs. Deflation, March 15, 2010

The China Bubble, June 8, 2010

National Debt and Rates of Return, December 12, 2010

When is Debt Unsustainable, February 4, 2011

For much more, refer to “What Percent of Payroll Will Keep Pensions Solvent?,” July 23, 2011, and the couple dozen links to related posts provided below the text.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!