The Abundance Choice (part 6) – Biased, Hostile Media

You can say this for Michael Hiltzik, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Los Angeles Times columnist for the Los Angeles Times: He doesn’t conceal his biases. When we talked in late November, his skepticism concerning our initiative felt overt. And while that may only have been my subjective impression of our conversation, Hiltzik’s column, published as a “Perspective” piece by the Times on December 2, removed all doubt.

Hiltzik’s column was called “This proposed ballot measure would make you pay for the ag industry’s water inefficiency,” and featured on page two of the print edition’s front section. Hiltzik fired an 1,800-word salvo at our campaign, making assertions, starting with the title, that were designed from beginning to end to convince readers that we were pushing a terrible idea.

In one of the opening paragraphs, Hiltzik wrote “In California, water is for scamming. The newest example is a majestically cynical ploy being foisted on taxpayers by some of the state’s premier water hogs, in the guise of a proposed ballot measure titled the ‘Water Infrastructure Funding Act of 2022’—or, as its promoters call it, the More Water Now initiative.” Nothing subtle there.

Hiltzik’s hits came one after another. He called the initiative “costly and dishonest,” claiming it would “wreak permanent damage to the state budget,” and “force taxpayers to pay for ecologically destructive and grossly uneconomical dams, reservoirs, and desalination plants.”

But Hiltzik’s bias against “wasteful and overly costly projects” may violate his own principles.

In an irony that ought not be lost on a journalist of Hiltzik’s stature, within a few weeks after he attacked our campaign, he wrote a column headlined, “Wall Street can now bet on the price of California water.” But Hiltzik can’t have it both ways. Either the state will help pay for water infrastructure with “wasteful” projects, or the price of water will rise to the point where private investors and financial speculators will end up dominating the industry. They will buy up farmland for the water rights and invest in costly, privately owned water supply infrastructure because they will then own that water and profitably sell it at a high price. That’s already happening.

Our initiative would socialize some or all of the cost of capital projects to increase the supply of water. This would lower the price of water in California. How can Hiltzik warn us about private-sector water speculators right after he trashed our plan to socialize a major portion of the cost of water supply infrastructure?

Of course Hiltzik’s report on our campaign included obligatory quotes from environmental experts, starting with Peter Gleik, co-founder of the Pacific Institute, which has a focus on “water conservation and demand management”—rationing, in other words. A column with more logical integrity would examine that premise. Is rationing enough? Gleik’s comment is predictable, given his background, saying “This proposed initiative is a desperate throwback to the idea that there is still more water that can be extracted from California’s already massively overtapped rivers and aquifers.”

But California’s rivers are not “overtapped.” They have inadequate or obsolete infrastructure which is not suited for an era of less snow and heavy, but erratic, rain. The appropriate new way to tap California’s rivers is by using off-stream reservoirs, percolation basins, and underground aquifers to capture storm runoff. And there is plenty of that.

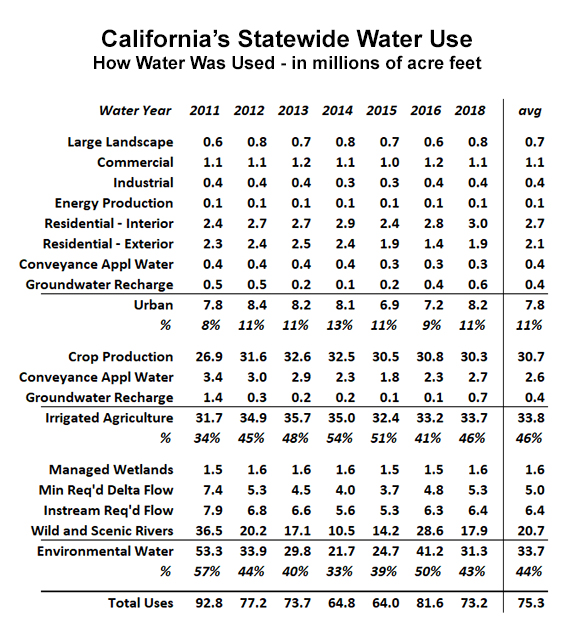

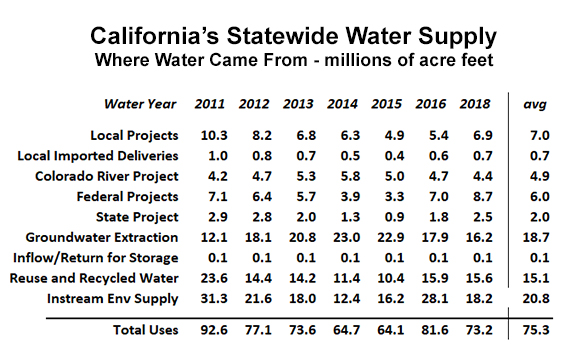

An authoritative 2017 study by the Public Policy Research Institute describes so-called “uncaptured water,” which is the surplus runoff, often causing flooding, that occurs every time an atmospheric river hits the state. Quoting from the study, “benefits provided by uncaptured water are above and beyond those required by environmental regulations for system and ecosystem water” (italics added). The study goes on to claim that uncaptured water flows through California’s Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta “averaged 11.3 million acre-feet [per year] over the 1980–2016 period.”

Let that sink in. Coming from some of the most respected water experts in California: The average quantity of “uncaptured water” flowing through the Delta that is “above and beyond those required by environmental regulations for system and ecosystem water” averages 11.3 million acre-feet per year. And we were just trying to find another 5 million acre-feet, with many options to accomplish that, including capturing storm runoff.

What Hiltzik wrote was unfair, but he was just one of many. Orange County Register reporter Martin Wiskol published a hit piece in December titled, “Environmentalists sound alarm over proposed water initiative.” If all you read are headlines, that headline sends a clear message (as does the rest of the article). The alarm bells are ringing! This is a bad thing! And we’ve become so used to this sort of bias, it’s hard to even imagine how an equally accurate headline for Wiskol’s article might have been “Grassroots activists propose common sense solutions to California’s water crisis.” Imagine coverage like that.

Leading off the media campaign against our initiative was the San Jose Mercury News with an editorial published on November 19: “Pull the plug on proposed California water ballot measure.” Typical of media and environmentalist critics of our initiative, it appeared the Mercury News’ editors hadn’t even read the initiative, as they wrote, “Historically, California’s water projects have been paid primarily by those who generate the most benefit. But this proposal would flip the scales. It would use general fund tax dollars to primarily increase the water supply for the state’s wealthy Big Ag interests.”

An honest fact checker would rate this assertion as “mostly false.” Our initiative would have funded projects to recycle 100 percent of California’s urban wastewater, at a cost estimated at around $20 billion. Our initiative would have funded remediation of urban aquifers, urban and small town water systems; it would have paid to replace the toxic pipes in the L.A. Unified School District schools. It would even have paid to restore portions of the Los Angeles River to its natural state. The only constraint was not funding, but retaining flood protection. But the Mercury News never bothered to ask.

For that matter, the editors at the Mercury News apparently didn’t even bother to read an article written by Paul Rogers, one of their staff journalists who for decades has been writing about water policy in California. Published two days earlier in their own newspaper, Rogers’ article was the only example of fair coverage of our campaign by a major media property. Rogers described our initiative as one that would “fast track” water projects in the state. But the exception proves the rule.

What would it take to get fair media coverage? It isn’t as if our initiative was anathema to environmentalist values and objectives. And it even called for more government spending, which typically attracts support from mainstream media. So why did the media attack our initiative without any attempt at balance or nuance? Why did they march in lockstep with environmentalists bent on destroying our effort before it got any real traction?

The answer to this may go back to one of the core premises of the modern environmentalist movement, backed up by the media, which is the belief that a middle class lifestyle is unsustainable. Humanity’s harrowing descent into a self-inflicted global “climate emergency” is the dominant message we get from environmentalists today, and it is reflected uncritically by the media.

But the greatest transgression by the media isn’t that they accept and promote this doomsday message and suppress dissenting theories, although that is bad enough. What is worse is that every project environmentalists oppose, even when there is minimal connection between that stopping that project and preventing climate change, is opposed by the media. Examples of this are plentiful.

More housing on single-family lots will cause climate change, they maintain, but building high density apartments and condominiums will prevent it. Constructing roads will cause climate change, but constructing high-speed rail and light rail will prevent it. Responsibly thinning our forests with commercial logging will cause climate change, but letting them get overgrown and burn like hell every summer will prevent it. Had enough? For each of these examples, there are obvious and compelling counterarguments, but it doesn’t seem to matter.

Trying to explain what is behind the collective hostility of the media not just toward water projects that violate the climate emergency narrative, but against all development unsanctioned by environmentalists, is the topic of another essay. But a big part of the problem is there isn’t much of an alternative narrative, because there isn’t much of an ecosystem of organizations promoting an alternative narrative.

Notwithstanding media bias, one of the reasons there aren’t more quotes from experts in favor of more water infrastructure is because there aren’t enough organizations promoting water infrastructure, and the ones that are out there are underfunded, do not allocate resources to mobilizing grassroots support, and behave with an abundance of decorum and a scarcity of passion. By contrast, whenever there is a public meeting for or against a water project, the Sierra Club can be relied on to have mobilized dozens if not hundreds of their members to show up. Where are the statewide organizations that can mobilize hundreds of activists to show up at meetings in favor of more infrastructure?

Maybe that idea was ahead of its time, but life is unaffordable in California for a reason. It’s time now for organizations that support fewer regulations and more infrastructure spending to get more aggressive. Meanwhile, can anyone reading this name one expert in California in favor of more water infrastructure who has managed to make it onto the shortlist of people journalists call whenever something is proposed that might increase California’s water supply? I can’t think of anyone.

Without organizations willing to unite to make the case for more water infrastructure on the same scale as the environmentalist dominated organizations that only promote rationing, all that is left is the competence and integrity of journalists. On that topic, Kristi Diener, a media expert and key member of our steering committee who has interacted with journalists on water issues for many years, had this to say:

“There is a lack of critical thinking in the media. There are many facets to this. If someone makes an argument like, ‘Why should taxpayers pay for capital projects?’ they stop there without exploring the benefits which more than balance the expense. For example, there are projects that enable groundwater recharge and reduce the implementation costs of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, dilute toxic contaminants in well water and replenish wells which eliminate the need for the emergency bottled water delivery program, and arrest subsidence and the sinking of multi-million dollar vital infrastructure which reduces the millions of tax dollars necessarily being allocated to these fixes. Because creating water abundance also lowers water bills, and enables our farmers to put more job-creating land back into production, consumers have more to spend. That economic enhancement to other businesses bumps up tax coffers for community services like police, fire, and education. The media relentlessly criticize beneficial water projects, but neglect any independent exploration. Their conclusions and written opinions effectively become predicated on one-sided, dead-end statements. This is lazy, incomplete journalism.”

Diener continued:

“Another facet to the lack of critical thinking occurs due to the fact that California’s water laws, Opinions, Management Plans, Flow Requirements, Acts, systems of water rights and exceptions to those, Endangered Species Act rulings, etc. have piled up for decades, if not all the way back into the 1800s. They are extremely complex and require explanations and interpretations from experts. But the fact-givers who are supposed to be the water experts and the keepers of the knowledge frequently either get it wrong, or intentionally cherry pick the data. The majority of the media is unwilling, or unable, to fact check the fact-givers. For years the media has accepted what they are told, and the result has been generations of widely spread misinformation packed onto the public, who now believe they know the facts. The difficulty in promoting more water infrastructure sometimes is in having to rewind and replace what people think they know to be true, with the parts that have been omitted that make those arguments false.”

It is unlikely the bias and hostility of the media towards more water supply infrastructure will change on its own, or before Californians run out of water. But it is possible that some of the special interests that currently either oppose water projects or sit on the sidelines, will change their priorities and begin to support new projects. Ultimately, and perhaps contrary to their own self-perception, journalists as a group tend to reflect and promote the political preferences of the elite influencers that own or advertise on media platforms. For that reason, we may hope that if the consensus on water policy among elites begins to shift in our favor, that shift will be reflected and accelerated by members of the media.

When it comes to projects to increase the water supply in California, the media today is predictable and hostile. Scarcity is good, development is bad. Somehow they’ve internalized the false impression that more water supplies will only harm the environment, rather than consider the possibility that more water creates more options for maintaining the health of ecosystems. And California’s journalists are apparently blind to the economic fact that water scarcity only serves the interests of investors and speculators who want to privatize and profit from high-priced water. It harms everyone else.

California’s hostile media can change its tune. But it will take enlightened altruism—i.e., demanding more water supply projects without further delay—from a critical mass of California’s moneyed elites, helped along by massive anger from California’s disenfranchised grassroots.

This article originally appeared on the website of the California Globe.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.