A recent article in the New York Post nicely encapsulates the latest developments in the ongoing debate over climate and energy. In his article entitled “If the Ukraine war hasn’t scared the West straight on energy, nothing will,” author Rich Lowry reminds us “The world hasn’t embraced fossil fuels out of hatred of the planet but because they are so incredibly useful.” He goes on to accurately observe that fossil fuels are used to produce 84 percent of global energy.

If there is only an alleged consensus on the potentially catastrophic threat represented by fossil fuel, there is widespread agreement on the direct connection between energy and prosperity. With that in mind, and to make clear how critical it is to produce more energy worldwide, much more, here’s an immutable fact, courtesy of data in the 2021 edition of the BP Statistical Review of World Energy: For everyone on earth to have access to half the energy, per capita, that Americans consume, global energy production will have to double.

Meanwhile, according to BP, wind and solar power accounted for 5.0 percent of global energy production in 2020. Five percent. And yet, unless you are a climate contrarian, also derisively referred to as a “denier,” wind and solar are not merely the favored solutions to global energy challenges, they’re the only solutions. But what’s wrong with this picture? Go wind. Go solar. Why not?

To appreciate what it’s going to take to create a global economy powered by nothing more than wind and sunshine, look no further than California, where the state’s policymakers are embracing these energy technologies to the exclusion of all others. The are undeterred by geopolitics, economic cost, social cost, or environmental impact. It almost appears that in their zeal to save the planet, they must destroy civilization.

California Leads the World in Ongoing Renewables Delusions

If you live in California, by now you’ve probably seen the ads, either on prime time television or online, exhorting you to “Power Down 4 to 9PM.” These ads are produced by “Energy Upgrade California,” paid for by “investor-owned energy utility customers under the auspices of the California Public Utilities Commission and the California Energy Commission.”

According to the mission of Energy Upgrade California, they are “a statewide initiative committed to uniting Californians to strive toward reaching our state’s energy goals,” and those goals include “getting 33% of our electricity from renewable resources by 2030.”

And it doesn’t end there. Over the past twenty years, through increasingly ambitious legislation and executive orders, California’s official state policy now aims to “achieve carbon neutrality as soon as possible, and no later than 2045.”

The misanthropic cruelty of these laws ought to be obvious. Normal people need more electricity between 4 and 9 PM, and no amount of public education can overcome that circadian fact. This is the time of day when normal people complete their daily work, prepare and eat dinner with their families, complete routine and necessary chores from doing the laundry to packing lunches for the next day. This is the time of day when people want to heat or cool their homes to a comfortable temperature, and power up all the countless electronic gadgets which are now required for everything from homework to paying the bills. They don’t want to wait till 9 PM to do any of this. By 9 PM they want to relax.

Normal people may also be forgiven if they don’t want to jump through the preposterous hoops required of “programmable” appliances, such as washing machines that will defer ignition until the spot price of electricity drops below a specified threshold. The fact that every major appliance now requires internet connectivity and comes with an instruction manual that rivals Lord of the Rings in scope and word-count is not a sign of progress. It is fetishistic excess. Future generations will marvel at the absurdity of this maddening, mandated attention to technology-driven minutia, and attribute it to the hubris of our times.

But beyond the fact that Californians remain quiescent while algorithms, megalomaniacal bureaucrats, and fanatical green nihilists take over and run their lives, there is the sheer impracticality of achieving “net zero” by 2050, if ever. In a narrowing of options that borders on perversity, the current vision for accomplishing this goal rejects any additional hydropower, requires the decommissioning of existing nuclear power plants, and the abandonment of all fossil fuel. Is that possible?

Accomplishing “Zero Air Pollution and Zero Carbon” in California

A professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University, Mark Jacobson, completed a series of simulations, culminating in a report released in December 2021 “that demonstrate the ability of California to match all-purpose energy demand with wind-water-solar (WWS) supply, storage, and demand response continuously every 30 seconds for the years 2050-2051. All-purpose energy is energy for electricity, transportation, buildings, and industry.”

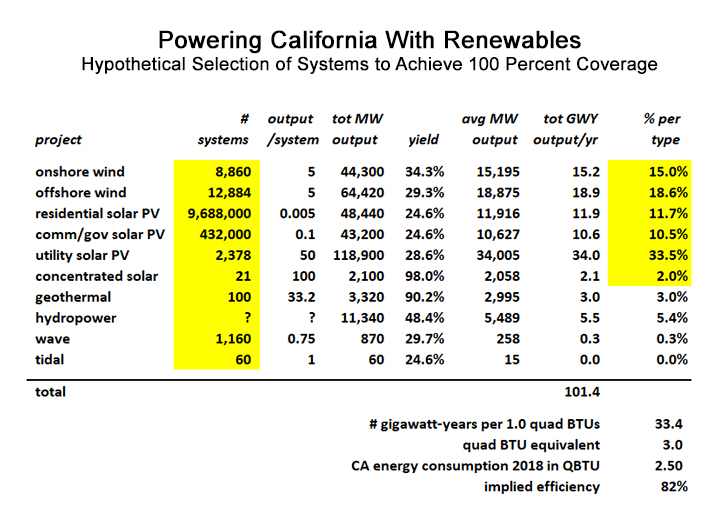

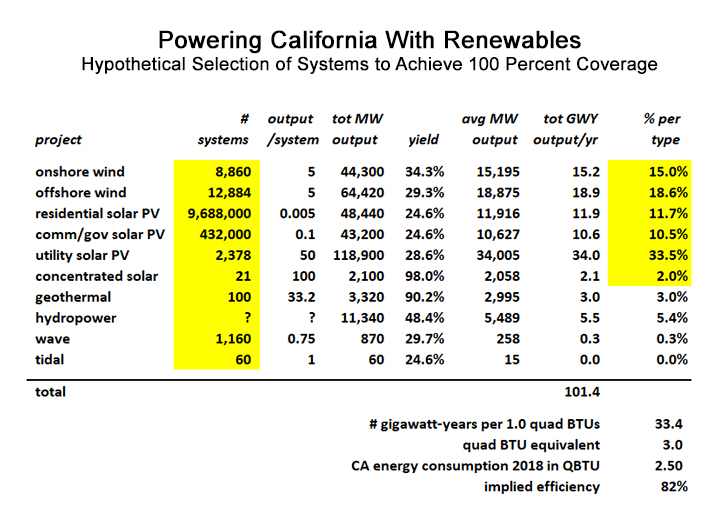

In this relatively unheralded study, Professor Jacobson has done Californians a huge favor, whether or not they support renewables. Because he has quantified a version of exactly what it would take, in terms of the installed base of renewable generating and storage assets to move California to a 100 percent net zero energy economy. Take a look at what Jacobson’s study envisions:

The first thing to note about Jacobson’s selection of renewable systems is that in theory, they would provide sufficient power to replace all legacy systems. The yields (column 4) assigned to each technology are reasonable, which means the total projected annual output as expressed in gigawatt-years, is also a reasonable estimate. Most economists measure total energy produced and consumed in quadrillion BTUs (British Thermal Units), and 101.4 gigawatt-years equates to 3.0 “quads.” In 2018, Californians generated 7.4 quad BTUs, but only consumed 2.5 quad BTUs. The rest was expended as “rejected energy,” primarily through the heat loss when using combustion based power systems including electric generating stations as well as individual vehicles. All-electric systems are far more efficient, and the implied 82 percent efficiency of an all-electric economy from source to user is not outlandish. So Jacobson’s numbers are tight, and assume – presumably via more conservation – no growth in energy consumption between now and whenever total renewable power is achieved, but they are nonetheless in the ballpark.

The other salient take-away from Jacobson’s renewables plan is that it’s all about wind and solar. Other renewables account for very little of the total; hydropower at 5.4 percent and geothermal at 3.0 percent.

Beyond considering the fact that the numbers probably work, however, is a more fundamental question: Do Californians want to live with 8,860 onshore 5 megawatt wind turbines, and another 12,884 of them floating or anchored offshore? Wind turbines of this size are truly monstrous, with a standard rotor diameter of 126 meters, i.e, 410 feet. Imagine a football field, including both end zones and then some, twirling around atop a tower more than twice the height of the Statue of Liberty, and you’re visualizing just one of these. They need a lot of land.

Rather than calculate merely the footprint of the wind tower, a more useful assessment of the land required for these wind turbines is the recommended spacing. An analysis published last year in the trade publication Energy Follower challenged the conventional spacing guidelines, which call for wind turbines to be spaced apart by a distance equal to seven times the rotor diameter. That alone calls for a stupendous amount of land, since that spacing would permit a maximum of four wind turbines per square mile. Citing work by Charles Meneveau, a mechanical engineering professor at Johns Hopkins University, the analysis went on to report that based on Meneveau’s analysis of the performance of utility scale wind farms, for maximum efficiency, “the suggested recommended separation of each turbine being 15 times the rotor diameter away from its nearest neighbors.” That equates to one wind turbine consuming 1.2 square miles.

Wind Power is a Grotesque Waste of Space

A legitimate conclusion that might be drawn from this data is that wind energy is not a desirable choice for Californians. To install 8,860 land based wind turbines would consume between 2,614 and 10,455 square miles, in order to produce only 15 percent of the required total energy in an all-electric economy. To put this in perspective, you could put 10 million new residents into homes, four per household, on half-acre lots, and you would only use up 1,953 square miles. Put them on still very spacious quarter acre lots, with an equal amount of land allocated for roads and commercial/industrial areas, and you’ve still only used up 1,953 square miles. California’s entire urbanized land only consumes around 8,300 square miles. To install these 5 megawatt wind turbines in a manner calculated to optimize their performance, a space greater than the footprint of every town and city in the state would be consumed. And this land would be uninhabitable – anyone who disagrees is invited to live on a wind farm. There will not be many takers.

When reviewing the above chart which estimates the land required for renewables, what is striking is the tremendous difference between the land required for wind farms versus the land required for solar installations. In order to generate 33 percent of the total energy, wind installations propose to consume over 10,000 square miles of land, and over 15,000 square miles of offshore ocean. By contrast, to produce 58 percent of the required energy, solar installations would consume just over 1,000 square miles, and much of that would be on top of existing roofs. Why not just use nothing but solar?

Answering that question goes to one of the hearts of the controversy over renewables, which is its intermittency. The need to balance between wind and solar, to slightly oversimplify, is that the wind blows more in the winter when there aren’t as many hours of sun, and during the summer doldrums when the wind is relatively still, there is plenty of sunshine. This seasonal variation is a bigger problem than the daily variation which underlies the “Power Down Between 4 and 9 PM” campaign, because there aren’t enough batteries in the world to store power collected during, for example, July to be discharged in January, and there never will be.

Viewing maps of wind resources indicate onshore wind energy in California is a poor choice. Far better wind resources are found in the nation’s midsection, assuming that state-of-the-art wind turbines can reliably wrangle tornadoes and ice storms. Possibly more viable is the offshore wind potential in California, especially in the far north of the state, but whether or not offshore wind installations are truly cost-effective is a question that requires far more thorough analysis than we’ve seen to-date.

Ultimately, Californians may want to think very carefully about Jacobson’s analysis, since it is one of the few fully realized and thoroughly vetted visualizations of what it’s going to take to convert to an all-electric, renewables based economy. Set aside the staggering economic cost, and the necessity to import most of the raw materials and even most of the manufactured systems. Set aside the undeniable environmental and social cost of sourcing rare earth metals from nations with an appalling lack of human rights and from mining and manufacturing operations controlled by America’s strategic rivals. For the moment, don’t think about the impact of wind turbines on birds, insects and bats. Never mind the fact that the embodied energy represented by these massive manufactured systems requires years to earn its “carbon payback,” if it ever does. And then contemplate the army of “carbon accountants” and bureaucrats, siphoning a stupefying quantity of wealth out of the economy merely to administer the new scheme.

Never mind all that. Just consider the aesthetic footprint.

Think about what it would be like to have 8,860 wind turbines, each of them twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty, scattered throughout the state. Imagine 1,160 “wave” generators and 60 “tidal” generators, actually sneaking past a coastal commission that ties anything going up near the coast in decades bureaucratic delays. And as for over 15,000 offshore wind turbines, with the requisite undersea foundations and power cables and onshore maintenance facilities. Does anyone think any of these will ever be built, much less 15,000 of them?

California’s energy economy, like that of the world, needs to reject narrow solutions. To produce the economic resilience and fulfill the obligations of a responsible government, California’s legislature needs to restore an all-of-the-above approach to energy. It needs to reembrace natural gas power and explore promising new ways to use it even more efficiently. It needs to approve nuclear power plants using the latest technologies. It needs to consider new sources of hydroelectric power – especially for pump storage on off-stream reservoirs which is one of the most cost effective ways to store surplus renewable power. It needs to weigh the total impact of wind energy taking into account its insufficiently acknowledged environmental, economic, social, and aesthetic cost. And it needs to nurture solar energy development, but not to the exclusion of conventional sources of energy.

It is ridiculous that Californians, living in the wealthiest, most innovative place on earth need to “power down” during precisely the moments in their daily lives when they need to power up. It’s time for California’s policymakers and opinion leaders to acknowledge this, and start acting on behalf of the citizens they serve, instead of special interests and their activist cheerleaders.

The Agenda of California’s Ruling Class is No Joke

Before merely laughing at California’s folly, recognize that this state is home to Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Twitter, Google, Intel, and a host of related social media and technology companies which collectively represent the largest concentration of wealth in one place in the history of the world. It is also home to Hollywood, which remains the primary arbiter of mainstream culture in the United States. California may be diminished by its government’s unrelenting hostility to business and working families, but an emaciated eagle still dwarfs the sparrows.

The model for governance that California is implementing, with the wholehearted approval and complicity of other blue states accompanied by the elites of most of the Western World, is oligarchy. They have determined that a middle class lifestyle cannot be sustained in America, much less exported to the aspiring nations of the world, and oligarchy, or neofeudalism, is their answer.

The conflict between Russia and the Ukraine, and the energy shortages that are its inevitable result, may awaken Americans to the futility of moving headlong into an energy future that excludes every form of energy apart from wind and solar. But that awakening needs to embrace not merely opposition to the green tyranny with its epicenter in California. It needs to embrace a moral crusade to double the energy produced in the world as soon as possible. In this quest, all fuels should be used, incorporating the cleanest technologies possible. At the same time, but over generations instead of within a few urgent years, new technologies can be developed that will eventually replace fossil fuel.

That is the path to peace and prosperity.

An edited version of this article originally appeared on the website American Greatness.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.