Unions and the American Worker

A great irony of American politics is that the agenda of the left, especially big labor, causes more economic harm than good to the average American worker. Explaining this irony is not easy, but a contributor to the Washington Times, Doug Ross, did a pretty good job yesterday in his guest column entitled “Union members should know their leaders are betraying them.”

Ross gets to the heart of the matter as he connects the money from union dues to support for big government bureaucracies whose current agenda is to curb economic growth while flooding the nation with cheap labor:

“When you get your next paycheck, take a minute to calculate how much money is going to union dues (say, for example, $90). Multiply that by the number of pay periods per year (say, 26). The total (in this example, nearly $2,500) is going to line the pockets of the union bosses who will give your money exclusively to one political party, Democrats.

Your money — the product of your labor, of your finite time on Earth spent working — is being stolen and funneled to the same political party bent on destroying you. The EPA is destroying jobs. The Department of the Interior is destroying jobs. The Department of Labor’s open borders advocacy is destroying jobs.

All of these immense bureaucracies, which you pay for with your taxes (more money stolen from you) are targeting union workers, America’s backbone. And these gigantic government regulatory bodies are doing so with the full knowledge and assistance of the union bosses who support Democrats.”

Not every premise Ross advances is necessarily correct. After all, Republicans have long demonstrated their willingness to be co-equals with Democrats in their subservience to big government, big labor, and big business. And open immigration would not be nearly so problematic if immigrants today weren’t entering a welfare state, where unionized public school teachers brainwash their children to embrace socialist ideology.

Ultimately what Ross is getting at is a corporatist collusion at the heart of union power. Despite common perceptions, big labor doesn’t hurt big business nearly as much as they hurt entrepreneurs who are the emerging competitors to big business. Big business often benefits when companies unionize, because their smaller competitors can’t handle the extra costs. Similarly, big business generally benefits from government regulations, such as new environmental regulations that are often overkill, because smaller competitors can’t afford to comply.

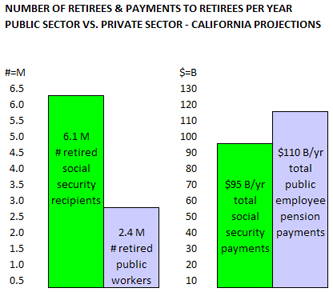

Perhaps the biggest irony of all is how unions now urge Americans to blame “Wall Street” for the economic hardships affecting working families. Because the relationship of big labor to big finance exemplifies the most corrupt example of corporatist collusion of all. At a time when the U.S. Federal Government is borrowing money at a composite rate of well under 1.0%, public employee pension funds pour hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars each year into Wall Street brokerages, under the fiction that these trillion dollar funds can earn 7.75%. This is a con job of epic proportions, and until the axis of big labor and big finance is broken by abolishing taxpayer-funded, high-risk, multi-trillion dollar Wall Street administered pension funds that promise high returns and high payments in perpetuity to unionized government workers, taxpayers will be on the hook to cover an awful spread.

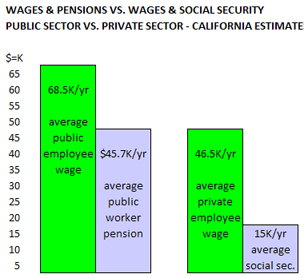

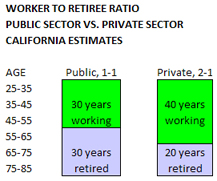

The last stronghold of labor unions is the public sector, where unions have indeed helped workers, but only public sector workers. The average total compensation for a unionized public sector worker – including costs for current and future benefits – is now twice that of the average private sector worker. The projected total retirement pension payments per year to public sector workers, who comprise less than 20% of the American workforce, are now projected to be more than the total projected social security payments to the other 80% of Americans.

With an agenda that only empowers monopolistic forces, big labor, big government, big business and big finance, the politics of labor unions essentially favor the same sort of political economy that was strangling competition and hurting the American worker back during the era of “trusts” in the 1890’s. The rise of the Tea Parties, which now has mushroomed into a generalized revulsion of the self-serving, taxpayer-funded power of public sector unions, is part of a seismic shift in American politics that will hopefully carry the same transformative force as the trust-busting movement of a century ago.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.