Time for California’s Unions to Get Serious About Pension Reform

There was a time, long long ago, when California’s pension systems were responsibly managed. They made conservative investments, they paid modest but fair benefits to retirees, and they didn’t place an unreasonable financial burden on taxpayers. But a series of decisions and circumstances over the past thirty years put these pension systems on a collision course with financial disaster. And like hybrid war, or creeping fascism, or a progressive, initially asymptomatic disease, it is impossible to say exactly when these pension systems crossed the line from health to sickness.

An excellent history of how California’s public employee pension systems moved inexorably towards the predicament they’re now in can be found in a City Journal article entitled “The Pension Fund That Ate California.” Written in 2013, when California’s pension systems were still coping with the impact of the Great Recession, author Steven Malanga identifies key milestones: The power of public sector unions that began to make itself felt starting in the late 1960s. The pension benefit enhancements that began in the 1970s. The growing power of the union representatives on the pension fund boards. Prop. 21, passed in 1984, which allowed the pension systems to invest in riskier asset classes.

The biggest milestone on the road to sickness, however, began in 1999, as Malanga writes, “when union-backed Gray Davis became governor and union-backed Phil Angelides became state treasurer, and the CalPERS board was wearing a union label.” The state legislation that followed, mimicked by local measures across California, dramatically increased pension benefit formulas. Not only were benefits increased, but they were increased retroactively, meaning that even state and local employees nearing retirement would receive the increased pension as if these higher benefit formulas had been in effect for their entire career. And as the internet bubble blew deliriously bigger, the experts said the cost for all these enhancements would be negligible.

In the aftermath of the internet bubble’s inevitable pop in 2000, pension systems engaged in accounting gimmicks and deceptive proposals to assist the unions to roll out these benefit increases to nearly every city and county in California.

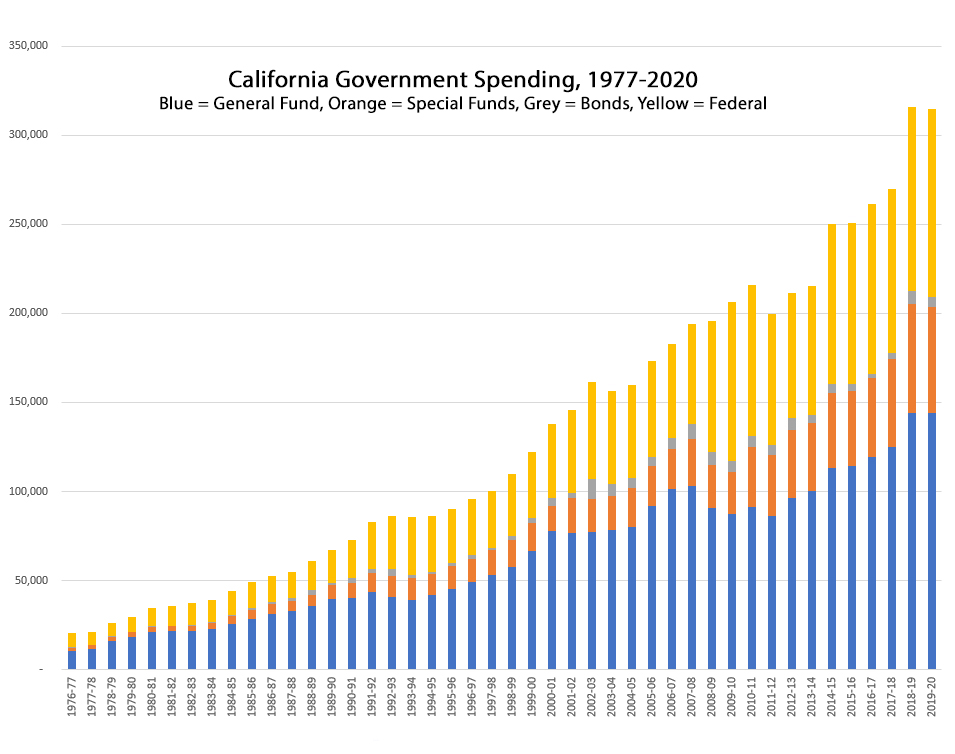

This would be an early example of how government unions and financial special interests saw an alignment of their political agendas, but it wouldn’t be the last. As payments to the pension plans inexorably increased, year after year, unions found common cause with the financial sector to market tax increases and bond measures. Every election, in lockstep, they would fight to convince the taxpayer to pay more and borrow more – and it was always for the children, for the elderly, but in reality, it was usually for the pensions.

The Burden of Public Sector Pensions on California’s Taxpayers

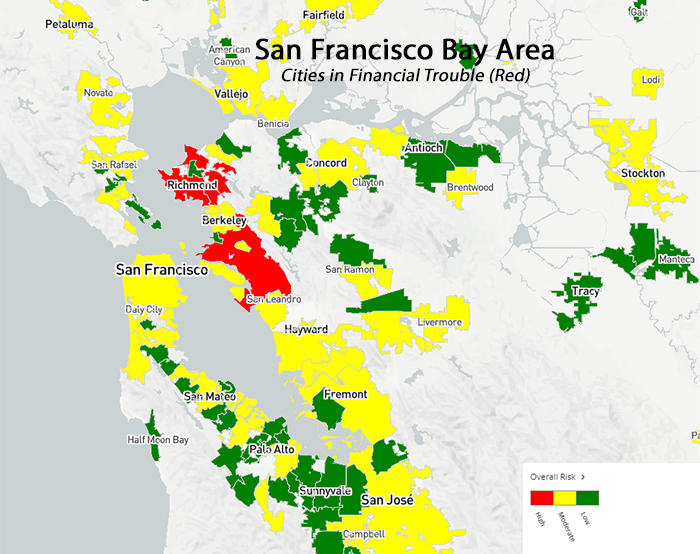

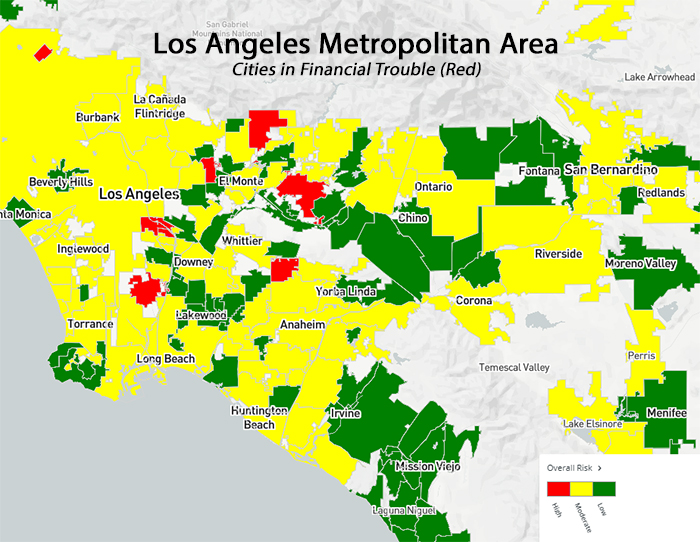

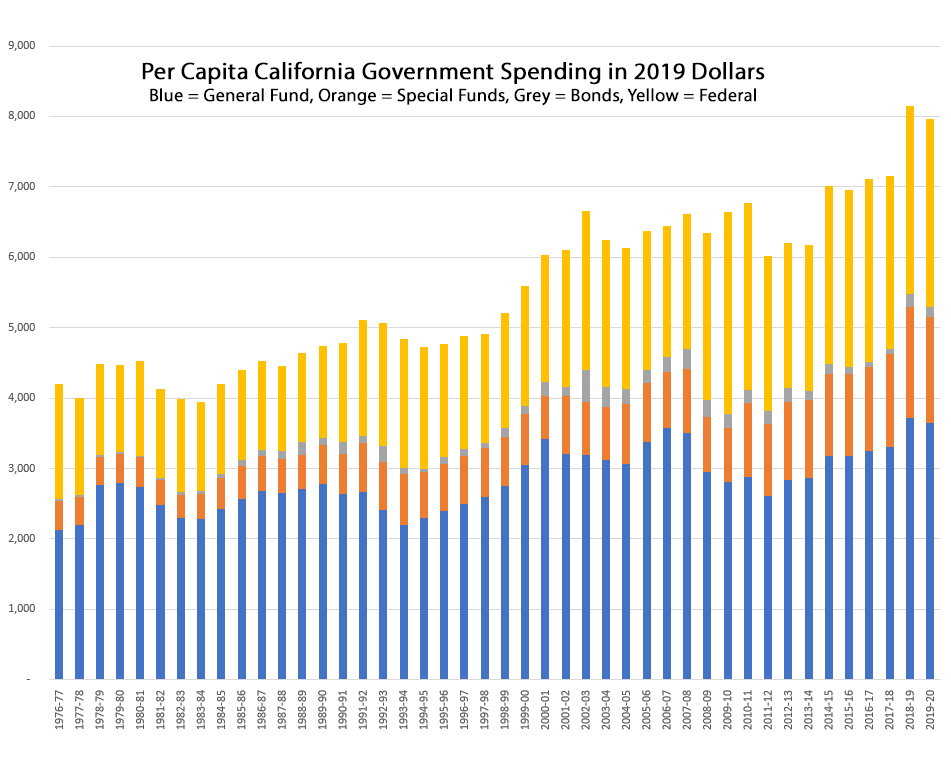

The complexity of pension finance makes it relatively easy to obfuscate the problem with creative accounting and emotional arguments. But certain facts can help to put the issue in perspective. Before the current financial crisis began, California’s state and local public sector pensions were estimated to rise from approximately $30 billion per year to $60 billion per year by 2025. Currently, California’s total state and local government general revenues are around $500 billion per year, meaning that pension payments are already set to consume over 10 percent of ALL state and local government revenue.

This ten percent doesn’t include the cost of retirement health insurance benefits, nor the cost for Social Security which many of California’s public employees also enjoy. It also doesn’t include the tens of billions spent every year by taxpayers to pay overtime, based on the fact that paying overtime is actually less expensive than paying for another government employee who will require another pension benefit package.

The pension burden, however, is about to get much bigger.

With most pension reform stopped in its tracks by relentless litigation, perhaps the only way pensions can ever be reformed will be through economic necessity. If so, now would be a good time. A perfect storm has struck. Here are highlights:

1 – The stock market has crashed. Interest rates are at zero, meaning it is unlikely investments in bonds will see continued appreciation. Real estate may also be at a peak, and in any case, real estate investment appreciation cannot make up for losses in stocks and bonds.

2 – Government revenues are going down for various reasons. California’s state government relies heavily on receipts from high income individuals, and those individuals rely on stock appreciation. These revenues always fall in a downturn, and this effect will ripple into every California city and county. Also, sales tax revenues, which local governments rely on, will dramatically fall over the coming few months.

3 – Californians for the first time in several election cycles have rejected local measures to fund taxes and bonds. Normally, at least two out of three new local tax or bond are measures are approved by California voters. This time, in March 2020, those proportions were surprisingly reversed, with about two out of three failing to get voter approval. This means new revenues these localities were counting on will not materialize.

A closer look at CalPERS will reveal just how dramatic the problem has finally become:

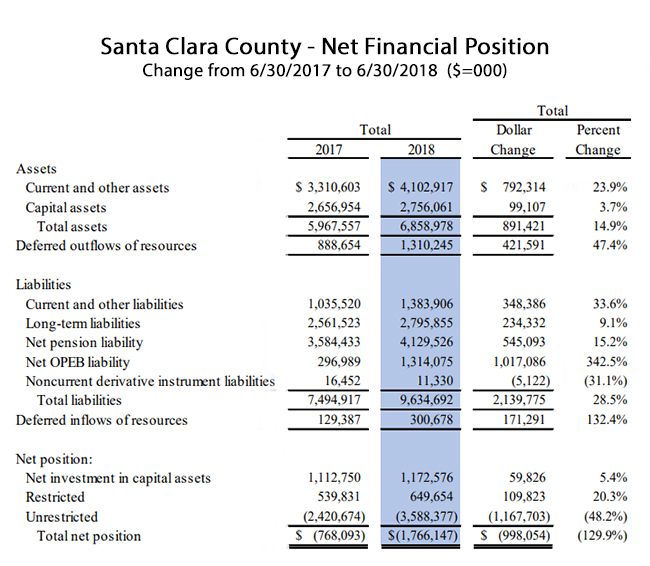

In their 6/30/2019 financial statements, CalPERS, the largest pension system in the U.S., reported themselves to be only 70.2 percent funded. To cope, the system was requiring its participating agencies to nearly double their annual payments by 2025. Needless to say, these increases were going to create havoc on civic budgets that already can barely afford to pay for their pensions.

That was then.

As of March 20th, the market value of all investments managed by CalPERS had fallen to $333.8 billion, after topping a record $400 billion just one month earlier. The most recent officially reported estimate of the total liability carried by the CalPERS system is $505 billion as of 6/30/208 (ref. most recent CalPERS CAFr, page 122). If you review the trends over the past decade, this figure has never gone down. This means, best case, as of today, CalPERS is 66.9 percent funded. The real number is almost certainly lower.

As of March 20, for example, the Dow Jones Index closed at 19,161. At close on 3/23, the Dow is down to 18,591, down another 3.1 percent. At this time, the only thing that is certain is uncertainty.

Pension Solvency Will Require Union Cooperation

If there’s one thing that history has shown, it’s that nothing gets done in California without the blessing of the public sector unions. One may argue on principle that unionized government is an abomination, having little or nothing in common with private sector unions which – properly regulated – have a vital role to play in American life.

But so what? California’s state and local governments have been taken over by these unions, who operate as senior partners to leftist billionaires, trial lawyers, race-baiting rent seekers, and environmentalist fanatics. For the most part, financial and corporate special interests are complete sell-outs to these all powerful unions, or survive via precarious detente.

Fixing pensions in California, with union cooperation, would be relatively easy. With union cooperation, politicians would have a chance to enact reforms that would not get mired in endless litigation. With union cooperation, government workers – and the public – would be able to learn about the extent of the problem instead of getting dosed with emotional propaganda. Possible solutions could be far reaching and inspiring. Here are some ideas:

1 – Reduce all pension benefit accruals to pre-1999 levels for all future work. Leave intact benefits earned to-date.

2 – Lower the long-term rate of return projection for pension assets to 6 percent.

3 – Lower the inflation stop-loss for retirees from the current 70-80 percent to 50-60 percent – provide for COLA reductions if economy encounters deflation.

4 – Raise the age of eligibility to 62 for all employees, with full benefits only available to miscellaneous employees at age 67 (same as Social Security).

5 – Implement additional “triggers” that take effect if funding falls below 80 percent, including suspension of COLA, prospective further lowering of the annual multiplier for active workers, retroactive lowering of the annual multiplier for active workers, reduction of the retiree pension payment, increase the required payment to the pension plan by active workers via withholding.

The pension systems themselves could assist this process greatly if they simply provided analysis of what measures 1 and 2 would accomplish. Lowering the rate of pension benefit accruals for future work will permit lowering the long term rate of return projection without increasing the total liability. If the pension system analysts could provide a table expressing that curve, it would greatly assist policymakers and reformers, including the union leadership.

Unfortunately, pension actuaries and fund managers do not have an illustrious track record in these exercises, so, again, it would be useful if the union leadership itself would insist on a quick turnaround and an honest, depoliticized assessment.

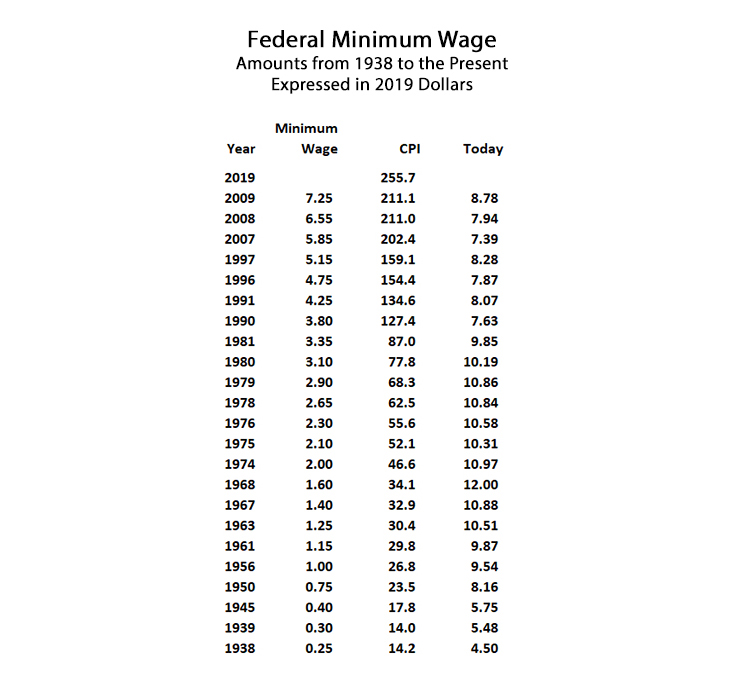

And what if, from now on, public employees earned lower pension benefits? First of all, it would take an awful lot before those benefits descended to the level of what the rest of California’s workforce can expect from Social Security.

An independent contractor in California has 12.4 percent withheld by the Social Security Trust Fund, and for that, they may expect a maximum of $36,132 after over 40 years of work; the average is $18,036. In 2015, the average pension for a California public employee after only 30 years of work was $68,673, not including any benefits. It is surely higher now.

What public sector union leadership might contemplate is how can the prospects for all workers in California improve. Now, with the economy grinding nearly to a halt, it is an especially good time for this sort of contemplation. Why not require CalPERS to invest 50 percent of their assets in “California based companies and projects” instead of the current 9.1 percent (ref. CalPERS CAFR, intro page 4)?

The idea that CalPERS and other pension funds were ever helping California’s economy is a blatant falsehood. The numbers are irrefutable. In 2018 CalPERS collected $28.7 billion, but only paid out 26.9 billion (CalPERS CAFR, pages 42 and 43). Since $3.5 billion of those payments were made to retirees living out of state, only $23.4 billion stayed in California. This means that Californians gave CalPERS $5.3 billion more than retirees living in California received in pension benefits. Meanwhile, over 90 percent of CalPERS investments are made outside of California.

What if public sector union leadership decided to fight for all California workers, by supporting reform of the California Environmental Quality Act, which would permit cities and suburbs to expand their borders onto open land again, greatly lowering housing costs? What if these unions supported pension fund investments in revenue bonds and equity positions to build new freeways, water storage projects, and cheap energy infrastructure? Imagine how much could be built if literally hundreds of billions of pension fund assets were invested right here in California!

There is a new consensus that could form in California, excluding the libertarian fanatics who think the only criteria for a pension fund investment is the return, even if it requires investing in Chinese slave shops. This new consensus could also exclude the identity-politics demagogues whose only criteria for a proper investment is the “diversity” of the workforce, the directorships, and the communities affected.

Who knows, maybe a new consensus could even knock the environmentalist fanatics – along with their trial lawyer and crony “capitalist” allies – down to size, allowing “green” investment criteria to resume its appropriate place within a kaleidoscope of worthy considerations.

If all these things were done, California’s cost-of-living would go down, meaning public sector retirees could enjoy the same standard of living as before, even if they retired with somewhat lower pensions. Moreover, the economy would be sizzling again, pouring record tax revenues into a solvent public sector.

The win-win envisioned here is no more preposterous than the notion of 7.25 percent pension fund returns for the next thirty years, and far more beneficial for everyone living in California instead of just beneficial for public servants.

This could be a time for a consensus that wipes away extremes, which might make CalPERS and the other pension systems a benefit to California’s economy instead of a terrifying drain. Public sector unions; the ball is in your court.

This article originally appeared on the website California Globe.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.