There is no special interest in California that wields more influence over state and local politics than public sector unions. At every level of government, from the office of the governor to a school board managing a district with only a few hundred students, public sector unions are omnipresent. With rare exceptions, to defy their agenda is certain political suicide.

The reason for this power is money. Lots of money. Every two-year election cycle, not millions, but hundreds of millions of dollars are spent by California’s public sector unions to support or oppose candidates, campaign for ballot measures, lobby the legislature, and pay for public relations campaigns. While wealthy individuals or powerful corporations may at times challenge these unions, their concerns are narrow in focus. Nothing matches the perennial torrent of public sector union money; the opposition may stir up a flash flood, but these unions are the Amazon.

Twice in the past five years the California Policy Center has attempted to estimate just how much money public sector unions collect and spend each year. In 2015, a rough top-down estimate that used US Census Bureau data on union membership and general assumptions on the average union dues payment came up with $1.0 billion per year. In 2018, exercising an abundance of caution, referring to the 990 forms that unions file with the IRS, as well as researching membership information that is often provided by the unions on their websites, the total public sector union spending estimate was $800 million per year.

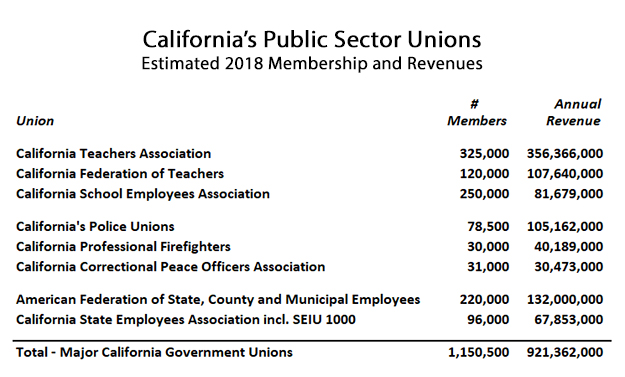

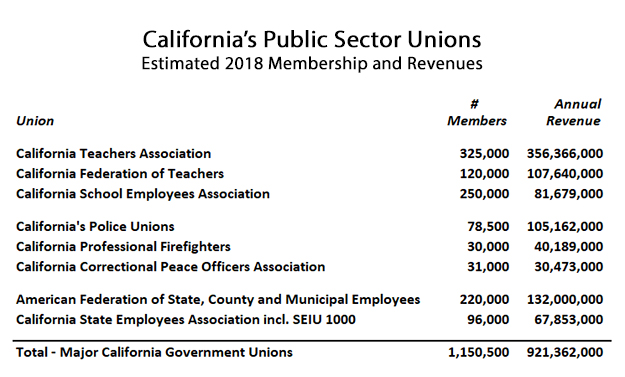

This time, using the same methods as 2018, but going into somewhat more detail, the new estimate is $921 million. It should be noted that available information online is usually about 18-24 months behind. For example, our 2018 report referenced Form 990s that were filed for 2015. This 2020 report used Form 990 data for the year 2018, the most recent currently available.

The fact that data presented here represents 2018 numbers raises an important question: Has the Janus decision, which found that the application of public sector union fees to non-members is a violation of the First Amendment, had any effect on public sector union revenue and membership? Because Janus took effect in mid-2018, the results shown here may only serve as a baseline. Form 990s for 2019 will not be available to the public for another year.

Moreover, unless the trends in total revenue estimates show truly dramatic changes, which is unlikely, there are too many variables at work to know what may be generating the variance. If the numbers are up, would they have been up higher without the Janus decision? Will any downward results in 2019 merely be the impact of unions losing non-members who still had to pay agency fees, or would some of the downturn be the result of losing members? How will the bureaucratic obstacles put up by the unions delay individuals from exercising their new rights under Janus? And how would one account for new bargaining units, such as the 45,000 child care providers who in July 2020 voted to become new AFSCME members?

Much of this discussion, however vital, falls outside the scope of this analysis. Here then is an assessment of just how much public sector unions collected in 2018.

PUBLIC EDUCATION UNIONS

The biggest public sector union in California, by far, is the California Teachers Association. From their website’s “About Us” page, the CTA’s declared membership is 310,000, down from the “Fact Sheet” they’d posted two years ago (since removed) which declared a membership of 325,000. On the surface, this may suggest the CTA has lost members, but in reality what was the CTA’s loss was another union’s gain.

As reported by EdSource in August 2019, the faculty associations representing 19,000 staff working in the Cal State University System voted to “disaffiliate” from the CTA. The CTA, for its part, claims new recruits have made up for this. Whatever the net effect will be, during 2018 these Cal State workers were still part of the CTA, so 325,000 remains a valid membership estimate for that year.

Using an average annual dues estimate of $1,040 per member, which is based on an analysis published in June 2018 in LA School Report, the CTA and all of its local affiliates had an estimated total dues revenue in 2018 of $338 million. The CTA also had “other income” in 2018 of $18 million, which brings their total revenue estimate up to $356 million.

A distant second to the CTA, but still one of the biggest public sector unions in California, is the California Federation of Teachers. Like the CTA, the CFT is comprised of separate local and regional affiliates, making the challenge of estimating their consolidated revenue best approached by multiplying their average dues by their stated membership. According to their “About Us” page, their membership is 120,000, and their average member dues, reputedly somewhat lower than the CTA at $900 per year, puts their total revenue at $108 million.

The California School Employees Association, which according to their “About Us” page has a massive membership of 250,000 school support staff, reported on their 2018 Form 990 total revenue of $81 million. This implies an average annual dues of only $327 per member, which seems low. Without reviewing the 990s for all of the CSEA affiliates, and accounting for the net effect of all internal transfers of funds, it is impossible to discern a more accurate number for CSEA. It may be that the number of CSEA members is a relatively low percentage of the number of people represented in their bargaining units.

PUBLIC SAFETY UNIONS

The decentralized nature of most of the major public sector unions in California makes any reasonably accurate but rough estimate dependent on two variables – total membership and average dues per member. To arrive at the number of members of police unions in California, we relied on an October 2018 Public Policy Institute of California study “Law Enforcement Staffing in California.” Quoting from the study:

“In 2017 there were more than 119,500 full-time law enforcement employees in California; roughly 78,500 were sworn law enforcement officers (with full arrest powers) and 41,000 were civilian staff.” We are assuming that 100 percent of the sworn law enforcement officers are unionized. If this is incorrect we would appreciate the opportunity to know the accurate percentage.

To arrive at the average union dues paid by California’s police officers, we reviewed the Form 990s for the unions representing sworn police officers in California’s ten largest cities. On these forms the “revenue from dues” is a separate line item. We then collected, for each city, the number of police officers on the force. In most cases, this information was available from the city websites, in a few cases, we had to rely on news reports, and in two cases, we called the police dept. in those cities and asked them. Using this method, the weighted average annual union dues we calculated was $1,340.

The product of average police union dues of $1,340 and 78,500 sworn law enforcement officers yields an estimated total revenue for all police unions in California of $105 million per year.

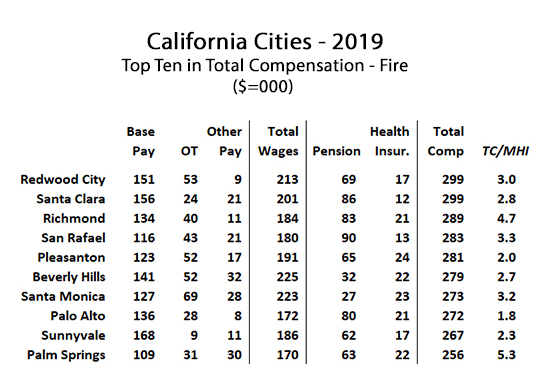

A similar method was used to estimate the total dues collected by California’s many firefighter unions, mostly local affiliates of California Professional Firefighters. On its “About CPF” page, the California Professional Firefighters claim membership of 30,000. Applying the same average annual dues assumption we used with members of police unions, $1,340 per year, we estimate the total dues collected by firefighter unions from their members at $40 million per year.

California’s prison guards are represented by the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA), a centralized union which reported on its Form 990 total revenue in 2018 of $30 million. This is consistent with a membership of around 31,000, implying average dues of $983 per year.

OTHER PUBLIC SECTOR UNIONS

Two very large public sector unions that belong in any analysis of public sector union revenue in California are the California affiliates of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), and the California State Employees Association which includes the massive SEIU Local 1000.

AFSCME California includes a diverse group of “Councils” that represent an impressive variety of professions. This can be quickly appreciated by reviewing their “Who is AFSCME California” webpage. From the information on these pages, along with phone calls to some of the actual Local offices, the total number of AFSCME members in California is estimated at 220,000 people. If anything, this estimate is low, insofar as some large agencies were unable to provide membership numbers.

Because the AFSCME dues assessment varies roughly between 1.25 and 1.5 percent, because a high percentage of AFSCME’s job descriptions involve skilled professionals, and based on conversations with experts on public sector unions, we believe an average annual dues collections estimate of $600 per year is reasonable, since even at the lower withholding percentage this implies an average member income of $48,000 per year. Based on these assumptions, we estimate AFSCME California’s consolidated dues revenue at $132 million per year.

Last but not least is the California State Employee Association, which includes three major unions of active state and local government employees. The Cal State University Employees Union, which declared revenue of $7 million in 2018, the massive SEIU 1000, representing 96,000 employees with revenue of $56 million in 2018, and the smallest of the three, the Association of California State Supervisors, representing 6,500 members with an estimated 2018 revenue of $4 million.

When it comes to the possible impact of the Janus decision, the 2017 and 2018 Form 990s for SEIU 1000 offer intriguing data. In 2017, SEIU had service revenue considerably higher, at $67 million. Understanding the reason for this drop, and watching the revenue trends over the coming years for all of California’s public sector unions, should make for interesting future analysis.

CONCLUSION

As shown on the following summary chart, California’s public sector unions collect and spend well over $900 million per year, or $1.8 billion per two-year election cycle. While only about one-third of this money is spent on explicitly political purposes such as campaign contributions and lobbying, this is still a staggering amount of money. What other special interest in California is willing and able to spend $600 million every two years on political advocacy, year after year, for decades on end?

And where the spending is not declared as political, it may still have a political impact. As the plaintiffs argued in the Janus case before the U.S. Supreme Court, and in the deadlocked Friedrichs case before that, all public sector union spending is inherently political. Public education campaigns, for example, are not considered “political,” but unions rarely embark on these efforts, often at levels where they saturate California’s expensive media markets, without at least an indirectly political motivation. And what about negotiations for compensation and work rules? Aren’t these political decisions?

When considering the total spending estimate here, it is worth emphasizing that in most cases these estimates understate the ultimate total. In every case, the average dues we assumed for our calculations of total dues revenue were lower than what virtually all anecdotal evidence suggests. And in only one case, the state branch of the CTA, did we include “other income” apart from dues revenue. How many of these unions and their many affiliates, most of them flush with cash and other invested assets, had additional revenue beyond just what they collected from their members?

Moreover, what about the many unions we didn’t identify here, but which are active in California and, cumulatively, add significant numbers to the estimates of total members and dues collections? What about the Council of UC Faculty Associations, an amorphous group that represents potentially tens of thousands of professors, associate professors, post-docs, etc.? Under what umbrella do these bargaining units fall? Were they excluded from this analysis? Probably. And what about the California Nurses Association? How many of their members work in the public sector?

To get another glimpse of just how Sisyphean the task of identifying and tracking all of California’s public sector unions is, have a look at this website, put up by the Freedom Foundation. Scroll down this page and consider the following: Were all of these various Locals included in this analysis? Here’s your answer: No. They weren’t. There’s simply too many of them. Some years ago, a professor at Pepperdine University who was considered an expert on public sector unions in California was asked if there was an accurate compilation, anywhere, ever, showing how much, collectively, these unions rake in every year. His answer, emphatically to the negative, was too obscene to be repeated here.

If anyone wishes to undertake a comprehensive analysis of every single public sector union in California, every state headquarters, every regional council, every Local, they’re welcome to it. The reporting requirements are almost nil. Unlike private sector unions, which are somewhat more accountable due to having to file the more detailed Form LM-2 with the U.S. Dept. of Labor, the only public disclosure required of public sector unions is the Form 990, mostly used for tracking nonprofits. The diligent analyst, using Form 990s, will have fun attempting to net out the thousands of cases where funds are transferred between affiliates – dues trickling upwards to regional, state and national offices, as well as sometimes horizontally between Locals, and sometimes from the top down. Have at it.

California’s public sector unions are not only the most powerful political special interest in the state, but most of them are nakedly partisan. To have all this power, and merely use it to push for more staff, more restrictive work rules (which equates to more staff), more pay, and more benefits, that would be bad enough. Not because workers shouldn’t want to optimize their opportunities to work and live with security and dignity, but because public sector unions simply do not have to deal with the natural checks on their demands that create more balance between management and private sector unions. But with only a few exceptions – primarily among the law enforcement unions – the websites of these public sector unions read like a pamphlet describing the agenda of the Democratic party. Is this appropriate? Does this represent the membership? And even if so, shouldn’t public sector unions, with all the power they wield, be politically neutral?

A long overdue reckoning with public sector unions faces California’s electorate. It might start with the public schools, which labor under a public sector union monopoly that has nearly destroyed accountability. The CTA, for example, has endorsed the absurd goal to “defund the police.” Perhaps defunding the CTA itself might be a more appropriate way to rescue California’s disadvantaged.

But between the political reality of public sector union power, and the necessary reforms that Californians desperately deserve, are nearly one billion dollars per year of cold hard cash.

This article originally appeared in the California Globe.

* * *

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.