The Once & Future Governor Jerry Brown

Yesterday the 71 year old Jerry Brown made his formal entry into the California Governor’s race. In a three minute announcement posted on www.jerrybrown.org, he highlighted his experience as well as took some indirect shots at his opponents. What kind of a Governor Jerry Brown was, and what kind of a Governor he would make, are an interesting topic for discussion.

Jerry Brown first served as Governor of California in the years 1975 to 1983. Elected when he was only 36 years old, Brown inherited a State that was experiencing one of the best economies in its history. The first efflorescence of the high-tech boom happened during Brown’s years as Governor, it was also the heyday of the west-coast aerospace boom. Other sectors of the State’s economy, from housing to agriculture, and everything in between, had not yet fallen prey to the plague of over-regulation and environmentalist gridlock that has since diminished opportunities in the Golden State. Brown presided over some very good years for California.

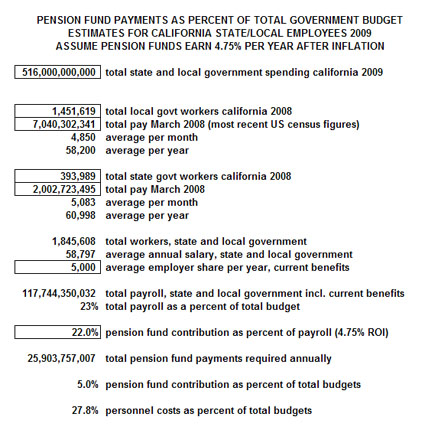

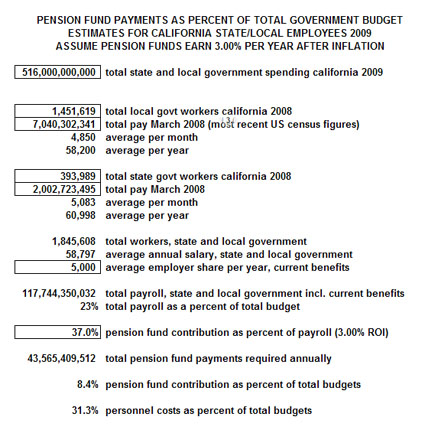

Brown is still criticized by mainstream journalists for being Governor when Proposition 13 was passed. This is guilt by association at most, he campaigned hard against the initiative. But when Prop. 13 passed, something happened that is instructive about Jerry Brown – he implemented it with a vengeance. He respected the will of the voters. Something the critics ignore, however, is that Prop. 13 didn’t hinder California’s ability to balance its budget, it was something else Jerry Brown did that caused our current fiscal crisis – his decision in 1977 to sign legislation allowing public sector employees to unionize.

The consequences of Prop. 13, which dramatically lowered property tax rates, have not led to insufficient tax revenue to California’s state and local governments. The culprit is public sector unionization, which has created an over-sized public sector workforce where, on average, workers cost about twice what people doing similar work requiring similar skills might cost employers in the private sector (when normalizing for current benefits and the funding requirements for future health and pension benefits). While this point is open to debate, it is relevant to note that Jerry Brown himself, in a very recent private appearance before a group of California business leaders, admitted the single greatest mistake he made as Governor back in the 1970’s was his decision to sign legislation allowing public sector workers to unionize. This fact – that Jerry Brown understands how the government bureaucrats, through their unions, have themselves taken over California’s the government, buying our elections, controlling legislation, determining their own compensation – is perhaps the most encouraging thing about Jerry Brown. At age 71, Brown isn’t thinking about his next career move. He may decide to take these guys on, and fix what he helped break so many years ago – our democracy.

Brown is rightly praised for having been a tight-fisted Governor, reining in spending even before Prop. 13 was enacted. He is also proven to be tough on crime, not only as Governor but also as Mayor of Oakland. These are formidable credentials for any Democrat running for office against moderate Republicans. But it should be noted that one of the reasons Governor Jerry Brown was able to rein in spending was because he canceled many infrastructure projects that California now desperately needs. California has a system of freeways, dams, aqueducts and power plants that is designed for a state with 20 million people, as the population edges towards twice that. If you are wondering why you are stuck in traffic, enjoying gridlock five days a week, Jerry Brown is part of the reason why.

This brings us to the biggest potential problem with Jerry Brown. Like his contemporary in high California office these days, Governor Schwarzenegger, Brown has bought the entire package of environmentalist extremism. In the name of fighting global warming, along with all the assorted environmentalist imperatives, Jerry Brown is one of the architects of artificial scarcity. This, too, is an assertion that invites in-depth debate, but Jerry Brown has aggressively and consistently supported environmentalist legislation. Here’s the problem with environmentalism when it gets out of balance and goes too far, as it has: It should be the goal of regulated public utilities, and public policy in general, to make resources cheaper, not more expensive. Contrived scarcity is an invention of misguided environmentalists, and it is championed by the rest of the Democratic machine because the funds that are gathered through taxation for “mitigation,” and additionally saved through deferred investment (since every infrastructure improvement is a crime against the planet), flow instead into the pockets of overpaid unionized public sector and public utility employees, who control our government. This connectivity eludes Jerry Brown, at least for now, and for this reason, he is potentially a very dangerous man.

What makes Jerry Brown intriguing is he is a wild card. He is independent-minded, he is intelligent, he is flexible, he is courageous, and he knows the system backwards and forwards. Journalists used to make fun of Jerry Brown for once recommending California start up its own space program. What is so bad about that? It would be a spectacularly better use of funds than overpaying public sector bureaucrats, or continuing self-perpetuating, corrosive entitlement programs. And it would yield spectacular technological spin-offs. Jerry Brown’s willingness to go out on a limb like this makes him a quintessential Californian, and the kind of visionary who could bring California back from the brink.

If Jerry Brown is elected Governor, the real question is not can he do the job, but who will show up? Will Jerry Brown accede to the reality of public sector union power and quasi-fascist environmentalist extremism – the power centers who currently are breaking California to their will, bankrupting us to line their pockets and salve their ideologies, and turning us, basically, into an occupied State? Or will Jerry Brown empathize with the seismic wave of populist sentiment that knows something is wrong, but can’t find coherent expression or clear solutions? Will Jerry Brown provide these answers – by reforming public sector unions, and developing infrastructure designed to reduce the price of resources instead of raising them? Jerry Brown has the capacity to make either of these scenarios our future. How he campaigns may provide clues to how he may govern, or not.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. He is also a senior fellow with the Center for American Greatness, and a regular contributor to the California Globe. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, Forbes, and other media outlets.

To help support more content and policy analysis like this, please click here.